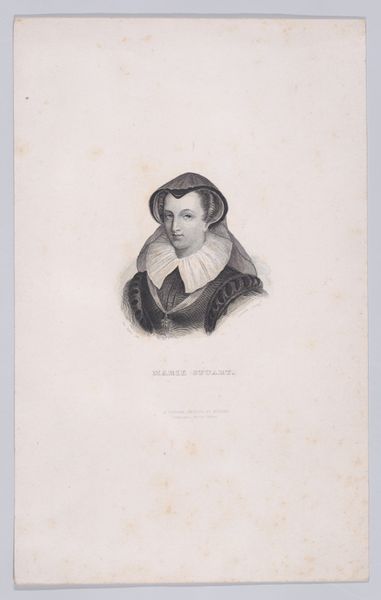

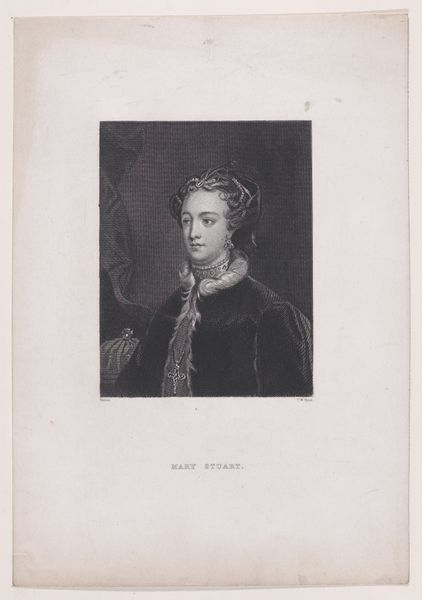

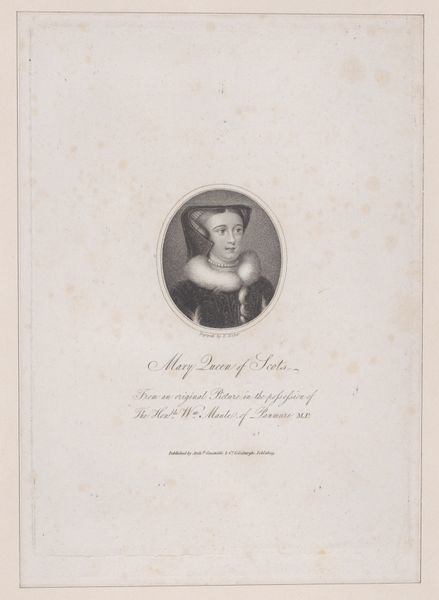

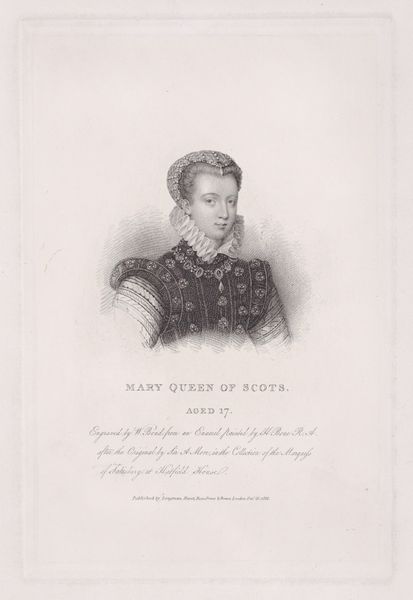

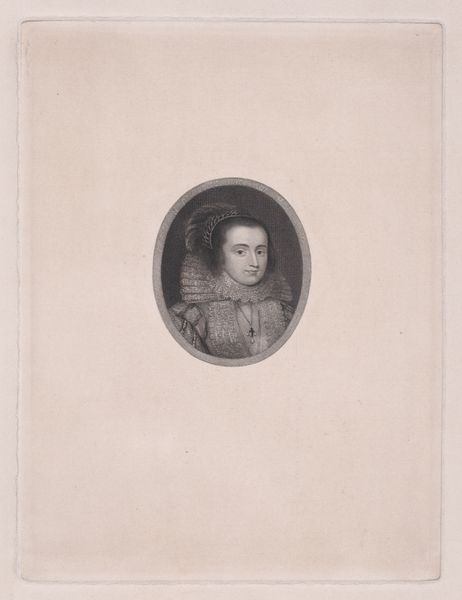

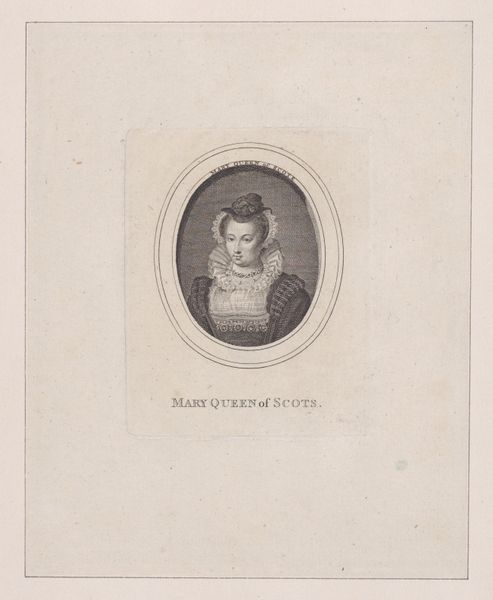

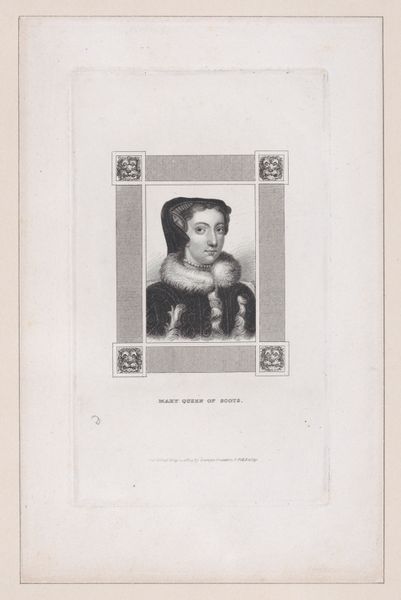

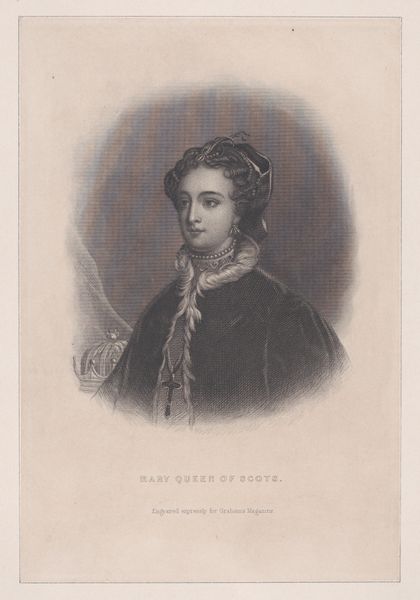

drawing, print, engraving

#

portrait

#

drawing

# print

#

pencil drawing

#

romanticism

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: Sheet: 7 1/2 × 5 3/16 in. (19 × 13.2 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Let's turn our attention to this print, "Mary, Queen of Scots" by Joseph Brown, created in 1844. It's currently housed here at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Editor: The starkness immediately strikes me. It's all grays and whites, lending this feeling of…historical remove, maybe even sorrow? You see her confined within that oval frame, with intricate, almost excessive decorative flourishes around the border. Curator: Exactly. Brown wasn't just interested in replicating her likeness. Consider the context. Romanticism was in full swing, idealizing historical figures. Mary, Queen of Scots, became a tragic heroine, particularly in literature and theater. Reproducing images like this fed a public fascination, especially in England, with her contested legacy. Editor: Which leads back to the medium. Engraving was how history became reproducible, widely available. How different it must've been than the original miniature that the engraving is referencing! The labor involved – the meticulous etching – it’s a deliberate act of reproduction and popularization, not just mere decoration, though some would consider engravings as merely applied arts. Curator: It’s interesting you mention that difference in scale. This print makes her accessible in a way a miniature, often a private, courtly object, never could. Mass production via engraving democratized imagery, placing her image into parlors and publications for a burgeoning middle class. The romanticized, even fictionalized, image starts to take precedence over historical complexity. Editor: And what about those adornments in the oval framing her? They feel significant. A sign of her status? Maybe hinting at the context of her story, the opulence but ultimate prison that royalty can be? Curator: Certainly. The flourishes and emblems frame her, both literally and figuratively. Think of how that visual language would speak to 19th-century viewers: the romantic glorification of monarchy mingled with moralistic considerations. This print isn't just a portrait. It's a carefully constructed narrative within the social and aesthetic norms of its time. Editor: So, through both the physical production and cultural reception, an engraving meant more than met the eye. Brown wasn't just presenting Mary; he was actively shaping a vision, accessible for mass consumption. It wasn’t passive but proactive, politically motivated, one might say. Curator: Indeed. What seems a simple reproductive print tells a bigger story about how art disseminates power, how images get mobilized, and the narratives we choose to keep alive through the ages. Editor: This has given me quite a new perspective on engravings; it feels vital to remember they, too, are material records, active participants in cultural movements and social narratives. Thank you for pointing all that out.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.