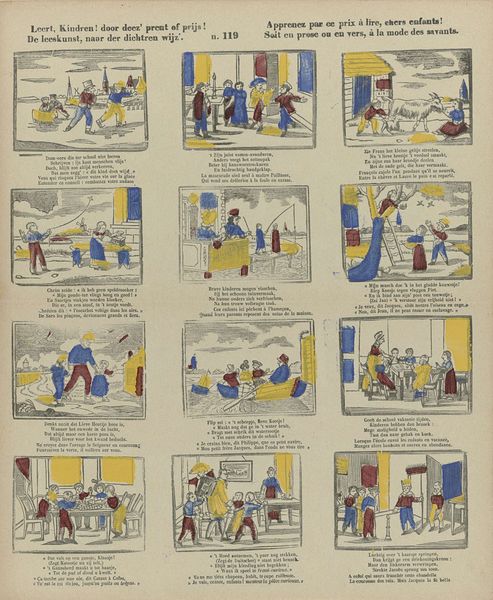

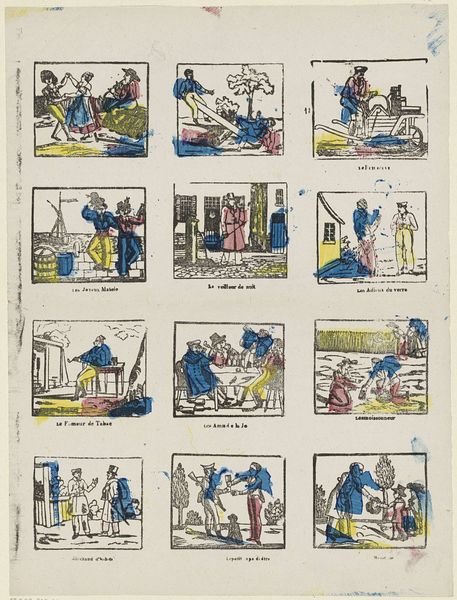

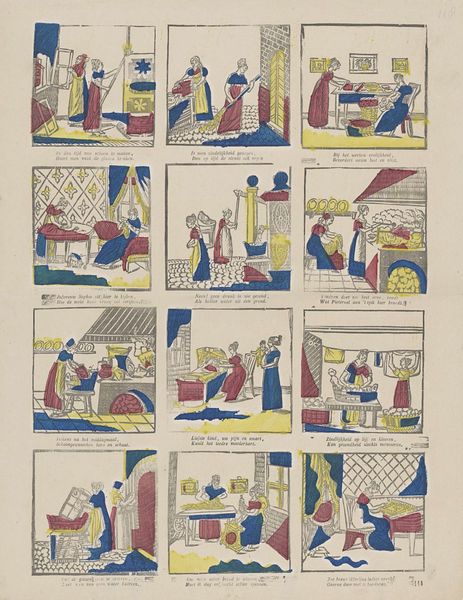

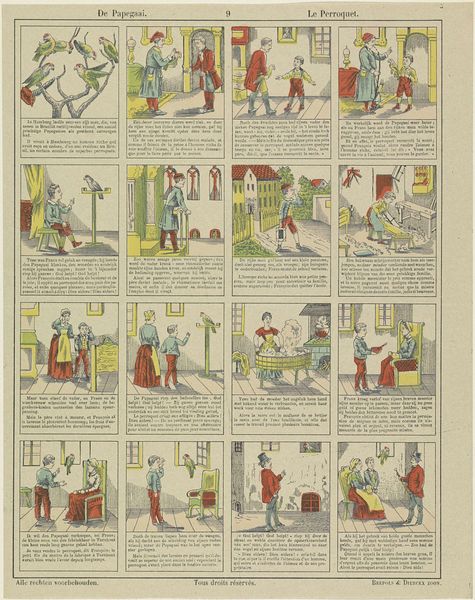

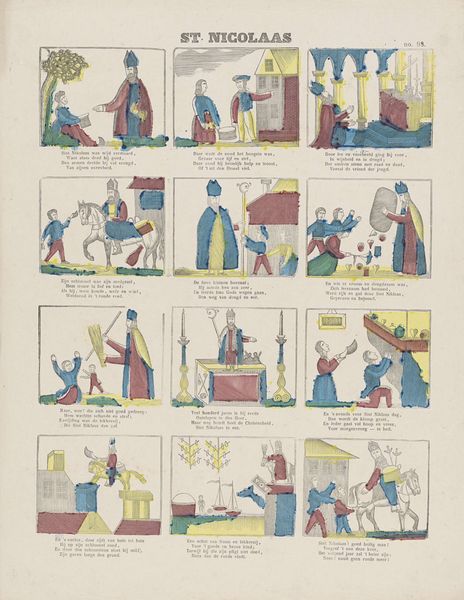

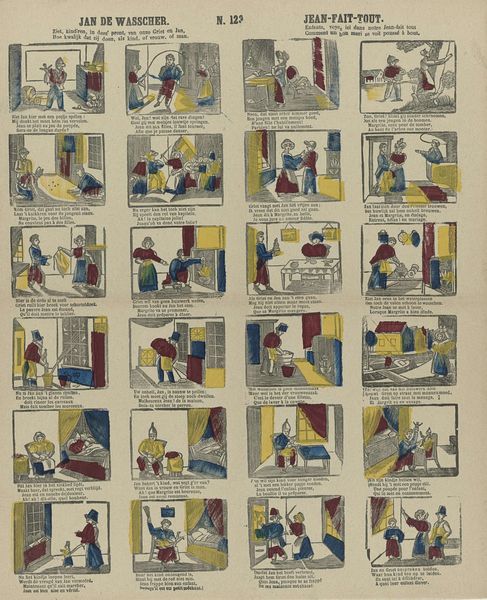

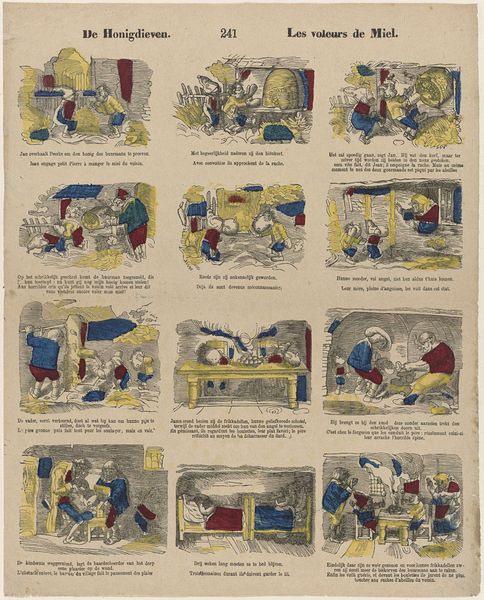

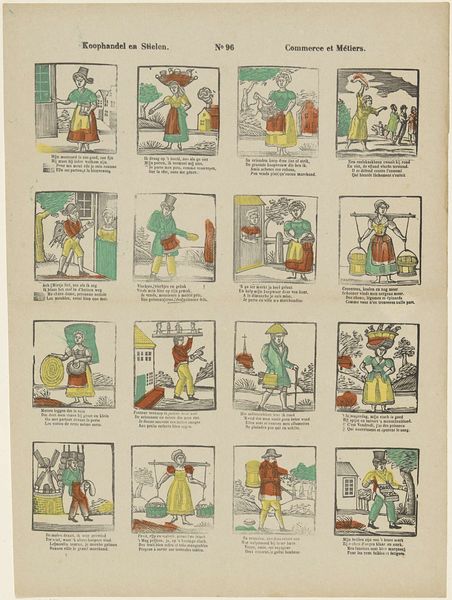

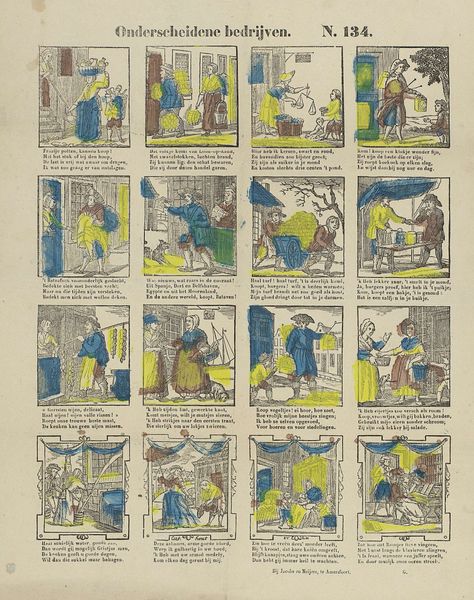

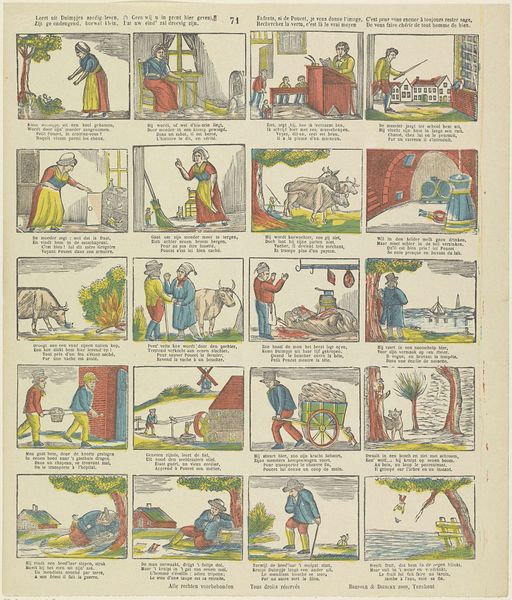

Leert uit Duimpjes aardig leven, ('t geen wij u in prent hier geven : ) / Zijt g'ondeugend, hoewel klein, dat uw eind' zal droevig zijn / Enfants si de Poucet, je vous donne l'image, c'est pour vous exciter à toujours rester sage; / Recherchez la vertu, c'est là le vrai moyen de vous faire chérir de tout homme de bien 1800 - 1833

0:00

0:00

philippusjacobusbrepols

Rijksmuseum

lithograph, print

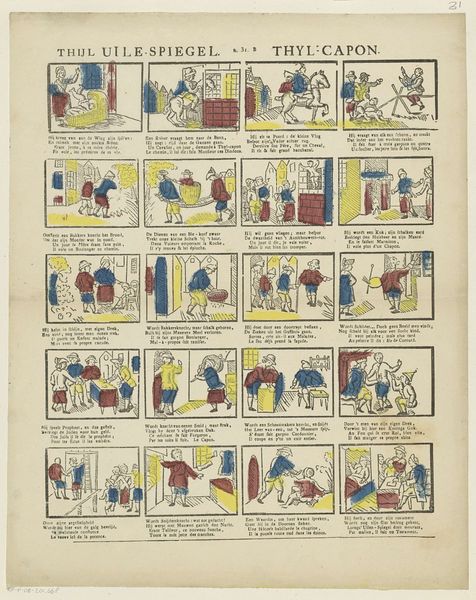

#

narrative-art

#

lithograph

# print

#

genre-painting

Dimensions: height 377 mm, width 312 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: We’re looking at a lithograph titled "Leert uit Duimpjes aardig leven…" by Philippus Jacobus Brepols, created sometime between 1800 and 1833. It's quite busy, a grid of little scenes. I’m struck by how much narrative it contains, almost like an early comic strip. How do you interpret the use of narrative here, given the time period? Curator: It's fascinating to see the use of such a sequential structure in what was effectively children's literature. The imagery here plays a didactic role, right? It seems to enforce specific behaviors. Consider the dual Dutch and French texts. What does it say about the intended audience and the cultural values being promoted? Editor: That's a great point about the dual languages; it definitely widens the piece's reach. And the little snippets of text act like captions, reinforcing the lessons within each scene. It almost feels like public service announcements packaged for children. Do you see these scenes as promoting a specific social order? Curator: Absolutely. Think about the rise of the middle class and evolving ideas about childhood during this period. Visual and textual rhetoric was strategically employed in printed materials. Images became powerful tools in shaping the morality of children and, by extension, securing social stability. How effective do you think these moral lessons were, presented in this form? Editor: Well, given how prevalent these kinds of prints were, they must have had some impact. Although, it also makes me wonder if children actively engaged with the "lessons," or simply enjoyed the stories visually. Curator: That’s an important point – the reception is always more complicated. This really makes you consider the purpose of art during that period and its potential role in society, doesn’t it? Editor: Definitely. It goes beyond just aesthetics and speaks to the cultural forces at play.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.