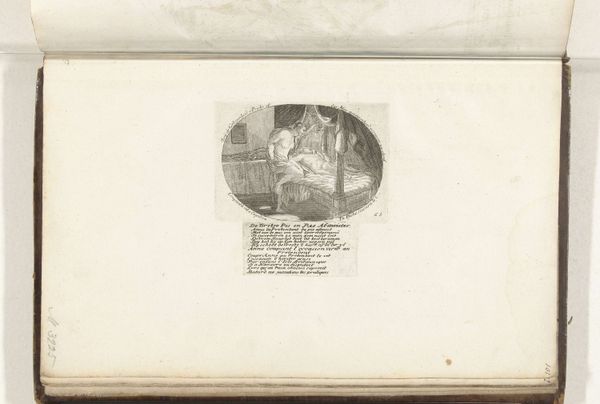

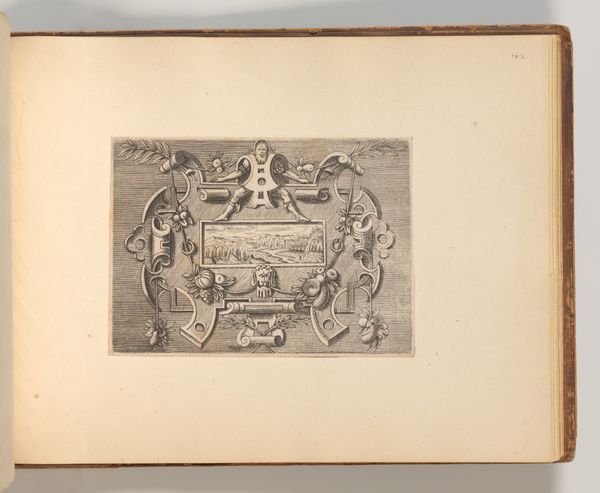

drawing, print

#

portrait

#

drawing

# print

#

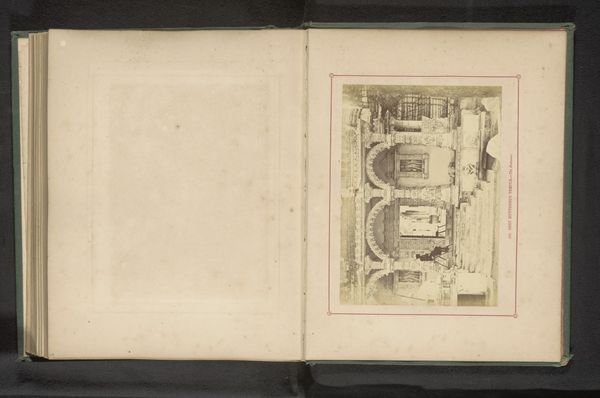

figuration

#

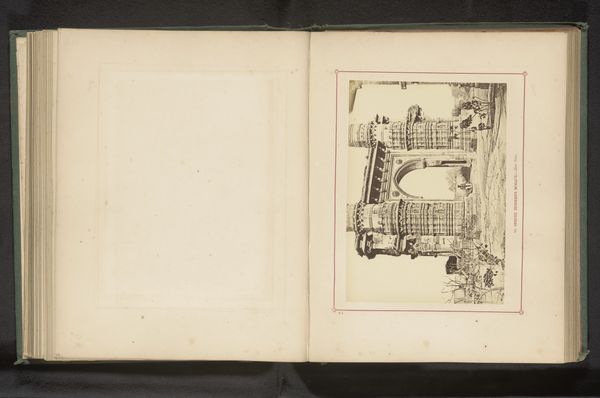

romanticism

Dimensions: Plate: 3 13/16 × 5 5/16 in. (9.7 × 13.5 cm) Sheet: 6 5/16 × 7 7/8 in. (16 × 20 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Ah, this delicate print. "Sophia," made by Henry Moses in 1809. It's currently housed here at the Met. Doesn't it evoke a certain quietude? Editor: Absolutely, I immediately noticed this feeling of tranquil domesticity. The scene is framed within an oval, giving it a sense of intimacy, like peering into someone's private world. But I also wonder about the power dynamics here – a woman in repose, perhaps defined by her domestic space? Curator: That’s a really interesting take! I find it more dreamy. Sophia is reading. The lines are simple yet there is an interiority captured through her gesture that reads more profound than constricting, wouldn't you say? I get lost in reverie imagining myself in her slippers… Editor: Perhaps, but consider the historical context. In the Romantic era, the domestic sphere was often presented as the ideal, almost the only, space for women. Even enjoying the apparent privilege of reading was circumscribed. Was she reading for pleasure or self-improvement in line with societal expectations? It makes me want to know what she’s reading. Curator: You always pull me back into reality with the right historical tug! The precision of the rendering really does call out the tension of that period. The print almost reads like a set design – perfectly balanced, a showcase for an enviable bourgeois life. Editor: Precisely. And notice the other framing device? A painting hangs within the scene – art within art – suggesting layers of representation and idealization. What are we really seeing? What are we meant to see? Curator: The piece begs so many questions. Do you think Sophia’s portrait itself challenges any of the conventions that dominated at the time? Or does it fully reinforce the stereotypes and traditional roles of women? Editor: I'd argue it perpetuates them, at least on the surface. But by questioning those representations today, by giving her a voice and recognizing those underlying assumptions, we are engaging in our own act of rebellion. We liberate her, in a way, don't you think? Curator: We do. That's why she's so much more than just a figure on a page—we’ve started breathing life into her, questioning and reimagining. The power of art never fails to move me, and us, along this spectrum of truth. Editor: Yes, it serves as a historical mirror and a springboard for contemporary thought. It compels us to re-evaluate inherited narratives and biases, even as seemingly still or tranquil as “Sophia.”

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.