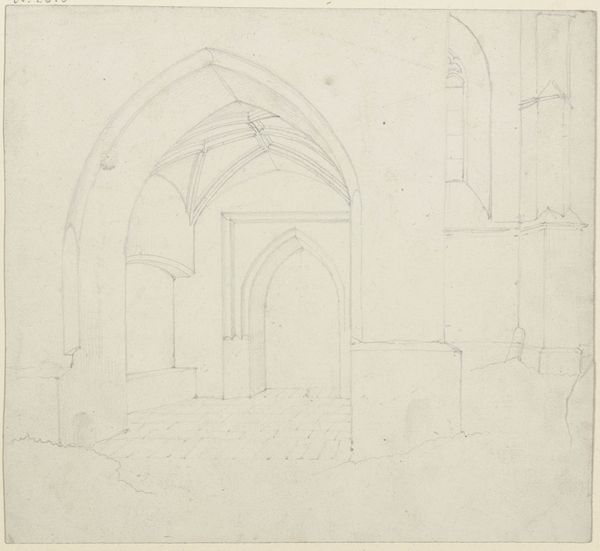

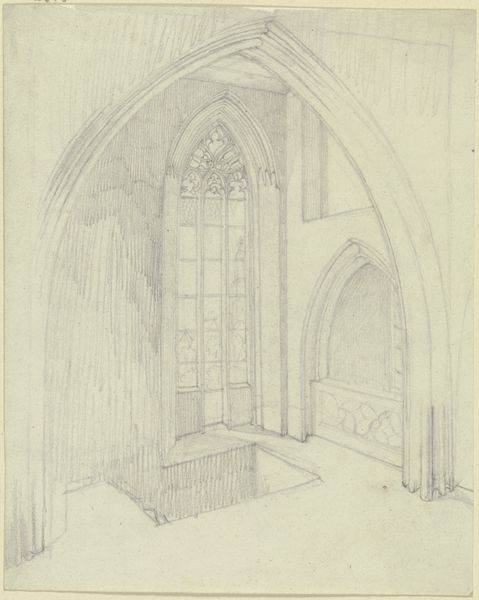

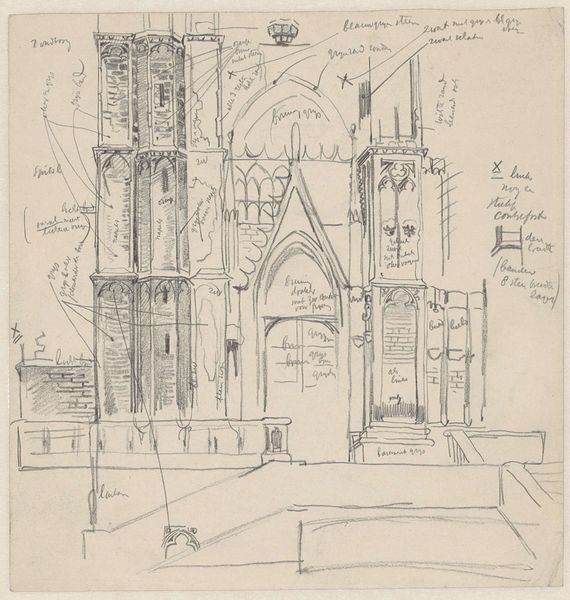

drawing, paper, pencil, architecture

#

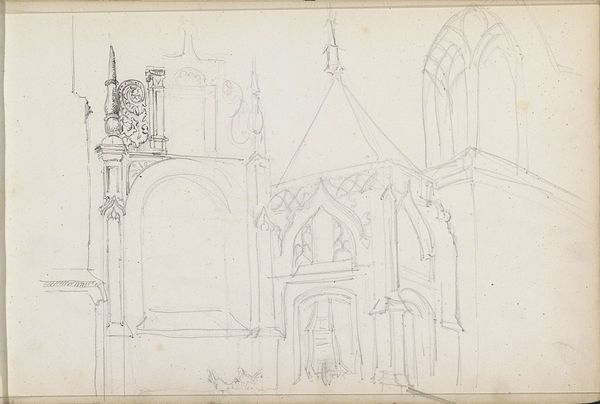

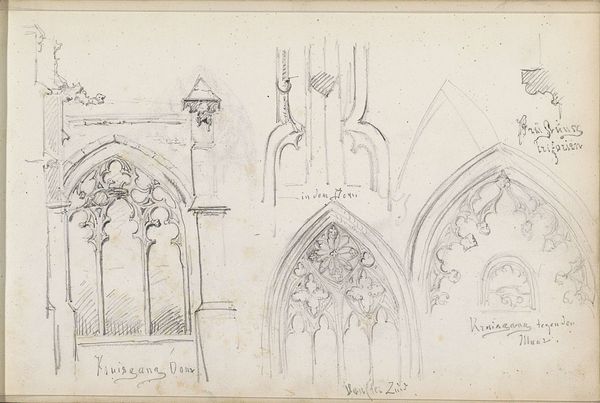

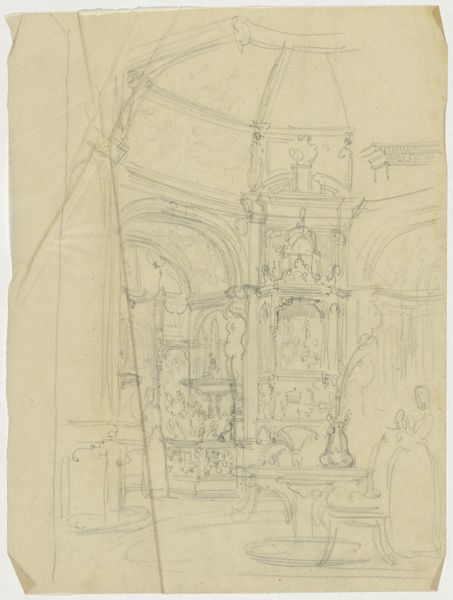

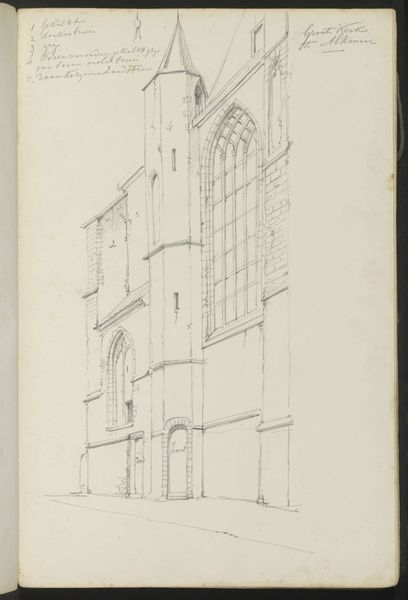

architectural sketch

#

drawing

#

amateur sketch

#

quirky sketch

#

sketched

#

incomplete sketchy

#

perspective

#

paper

#

personal sketchbook

#

idea generation sketch

#

sketchwork

#

geometric

#

romanticism

#

pencil

#

technical sketch

#

line

#

architecture

#

initial sketch

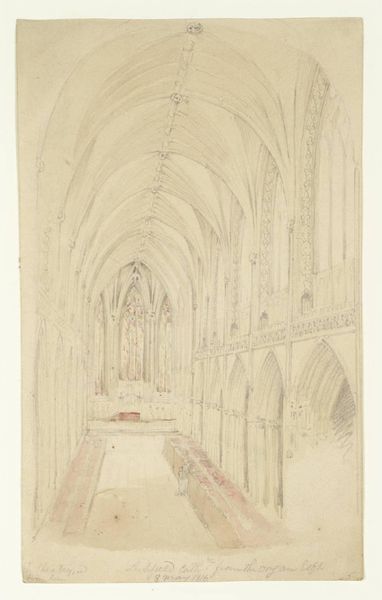

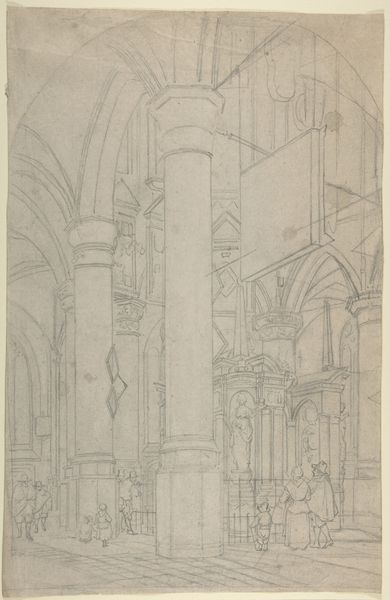

Dimensions: height 416 mm, width 290 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This pencil drawing on paper is titled "Schets van een kerkinterieur," placing it as a sketch of a church interior, and it’s attributed to Charles-Emmanuel Serret, likely created sometime between 1800 and 1900. Editor: My first thought is that this incomplete quality gives it a ghostly, almost melancholic feel. There's an architectural grandeur trying to emerge, but the hesitant lines hint at transience and fragility, evoking the ephemeral nature of structures themselves. Curator: That melancholy you perceive may stem from the convergence of several powerful symbols. The Gothic architectural style, even in sketch form, speaks of humanity’s reach towards the divine, a yearning for something beyond our earthly realm. But it is the Romantic sensibility of line that creates a longing for things beyond reach. Editor: I wonder, in the historical context, how accessible this architecture truly was. Were these spaces of solace available to everyone, or were they visually and physically imposing spaces of power reinforcing social hierarchies and gendered spaces of marginalization? The Church carries a heavy weight. Curator: Indeed. And the very sparseness of the sketch enhances that ambiguity. What is clearly emphasized is a focus on geometry. It’s hard not to think of how light filtering through those high windows would have felt, spiritually. Even incomplete, the suggestion is deeply felt. Editor: But what of the hands that erected these spaces? Who laid these foundations and were they able to partake? The history of these places is important and we should ask ourselves if their labour was respected within that geometric order you mentioned. Curator: Of course, such social inequalities cast a long shadow over this and so many artistic endeavors of the period. What's striking here, though, is how Serret focuses almost exclusively on the architectural skeleton—the skeletal framework of cultural faith. And if his hands drafted these plans, was he also a participant in upholding certain social inequalities by doing so? It's a reminder that artists themselves aren’t outside this framework, even unconsciously. Editor: Exactly! Seeing it not just as a detached, ethereal study, but as an artifact complicit in the physical and symbolic architecture of its time shifts the narrative entirely. We look for where faith rests in social justice rather than architectural majesty. Curator: It adds a crucial layer. Looking at it now, it invites me to look closer at all cultural frameworks. Editor: It is a starting point. It now sparks more difficult questions for me.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.