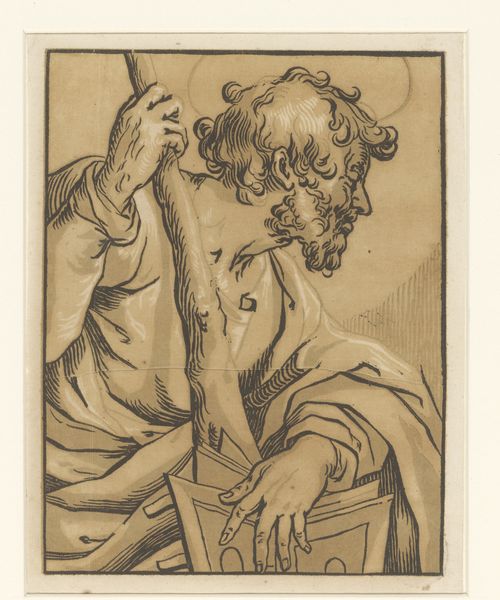

drawing, ink, pen

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

medieval

#

narrative-art

#

figuration

#

ink

#

pencil drawing

#

pen

#

portrait drawing

#

history-painting

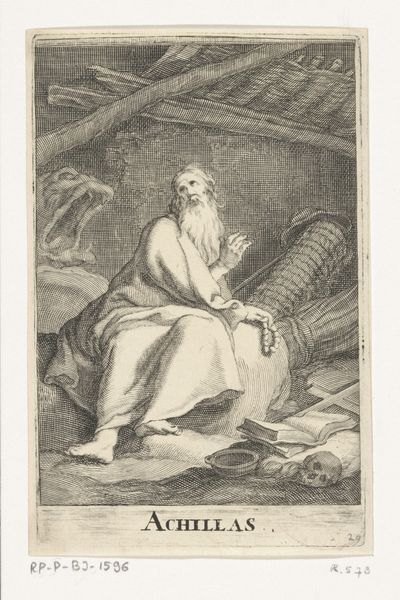

Dimensions: height 208 mm, width 160 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

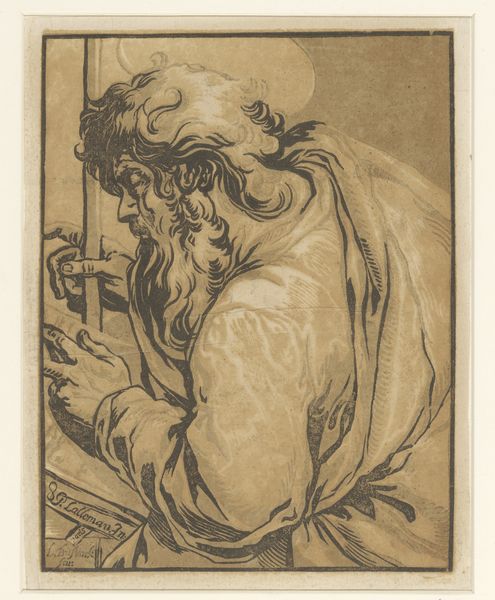

Curator: Here we have Ludwig Büsink's "Apostel Andreas," dating roughly from 1600 to 1669. It's rendered in ink, using both pen and brush, and offers a striking depiction of the apostle Andrew. Editor: My first thought is about the emotional weight conveyed. Despite being a drawing, it possesses this immense gravity. The deep cross-hatching really accentuates a somber mood, almost like he carries the weight of the world. Curator: Yes, Büsink's technique is fascinating here. Consider how the pen work, layered so deliberately, generates form, texture, and tone with great economy of material. There's little embellishment; it's fundamentally about skillful mark-making. The paper itself becomes an active participant, contributing to the overall aesthetic through its contrast. Editor: I see more than just material constraints; it brings up themes of sacrifice. Think of Saint Andrew, historically framed, then observe his gnarled hands and intense gaze. It evokes the turbulent 17th century in Europe, wracked by religious conflict. I cannot help but think how the intersection of faith, art, and patronage played out in the daily life. Curator: I'm especially drawn to how this contrasts with typical notions of 'high art'. There are parallels to be drawn with printmaking practices of the time, both of which often served a more accessible market, rather than just appealing to wealthy patrons. It suggests something of a democratizing trend. Editor: But even access has its complexities, right? Religious imagery circulated, definitely; however, control of the narrative, of how saints were depicted, always rested in hierarchical structures, church and the state, primarily. These portraits often shaped not only worship but social understanding of power dynamics too. Curator: True. We can admire the skill, appreciate the texture, the raw simplicity of ink on paper, and acknowledge, too, the socio-political landscape that both enabled and constrained this artistic expression. Editor: Absolutely. Understanding both the aesthetic qualities and how that period's intersectional powers influenced artistic outputs gives a more complex account of images we are now confronting today. Curator: So, appreciating the raw materials allows one path into understanding its legacy and context. Editor: Which inevitably asks one to acknowledge that art making and interpretation does not live within the confines of aesthetic experience; but within cultural ones as well.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.