oil-paint

#

portrait

#

baroque

#

oil-paint

#

figuration

#

oil painting

#

chiaroscuro

#

genre-painting

#

history-painting

#

realism

Dimensions: support height 85.5 cm, support width 70 cm

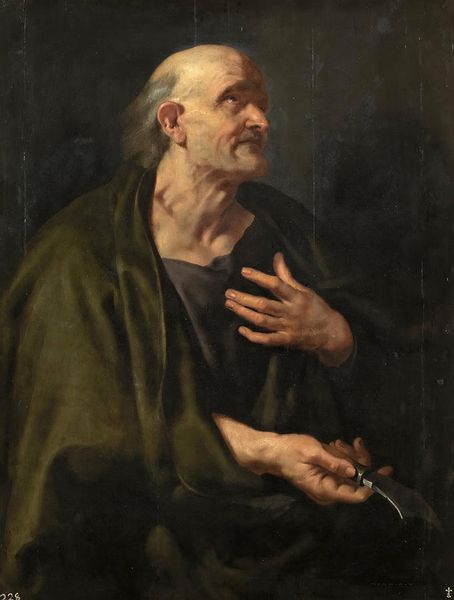

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

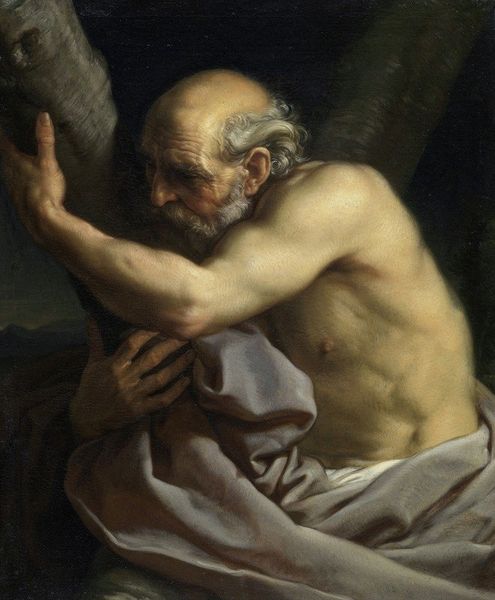

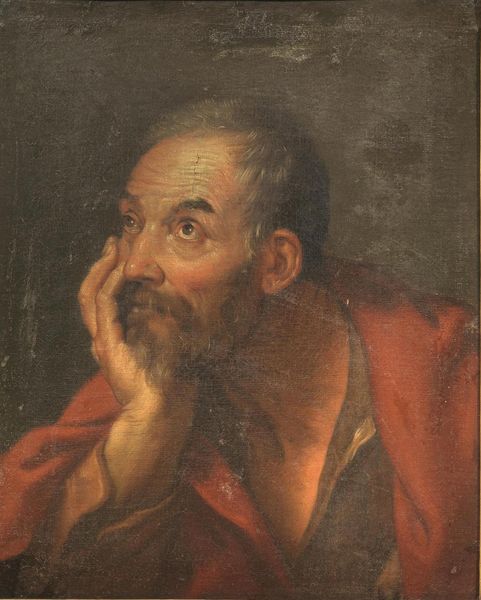

Editor: This is Hendrick ter Brugghen's "Heraclitus," painted in 1628 using oil. It’s quite striking – the way the light falls on his face and the globe makes him seem both worldly and melancholic. What's your interpretation? Curator: Brugghen's "Heraclitus" presents us with more than just a philosopher; it’s a poignant commentary on knowledge and power. The globe itself is symbolic, of course – a representation of the known world. But notice how Heraclitus isn't engaging with it, how his gaze is directed elsewhere, laden with sorrow. Doesn't that pose questions about what that knowledge truly means, and who benefits from it? Editor: I see what you mean. It's almost like he’s burdened by the weight of the world, rather than empowered by it. Is there a political dimension to this? Curator: Absolutely. In the 17th century, exploration and scientific discovery were intrinsically linked to colonialism and exploitation. By depicting Heraclitus as mournful, Brugghen subtly critiques the idea that knowledge automatically leads to progress. It’s about examining the ethics and consequences, don’t you think? It challenges us to consider the cost of expansion and the impact on marginalized communities. What is he really contemplating? The world's future, perhaps? Editor: So it's not just a historical portrait but a commentary on the present, even for Brugghen’s contemporary audience. That's amazing! Curator: Indeed. Art often functions as a mirror, reflecting not just the present but also prompting critical reflection on the past to shape a more just future. Editor: That really shifts how I see the piece. It's less about a specific philosopher and more about a universal human struggle with the implications of knowledge. Curator: Precisely! And that's where art history truly intersects with contemporary theory and philosophy. We’re constantly interrogating whose stories are told, and how.

Comments

rijksmuseum over 2 years ago

⋮

The Greek sage Heraclitus was known as the crying philosopher because he mourned the folly of mankind, while his opposite Democritus (the nearby pendant) could only laugh at it. Here Heraclitus looks like a melancholy old man. Downcast, he leans on a terrestrial globe and gestures dismissively with his left hand, as if to say: ‘All is for nought, the world will come to nothing.’

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.