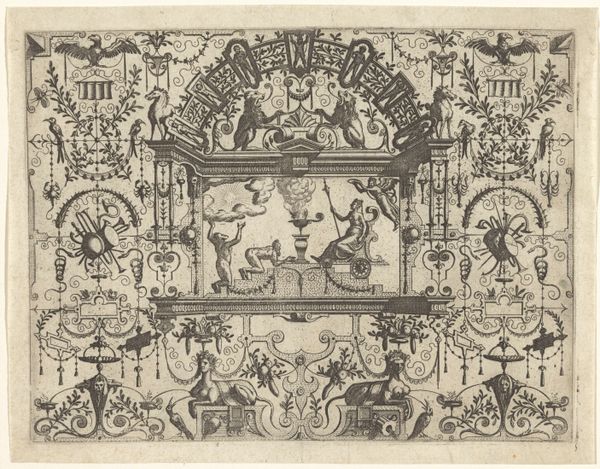

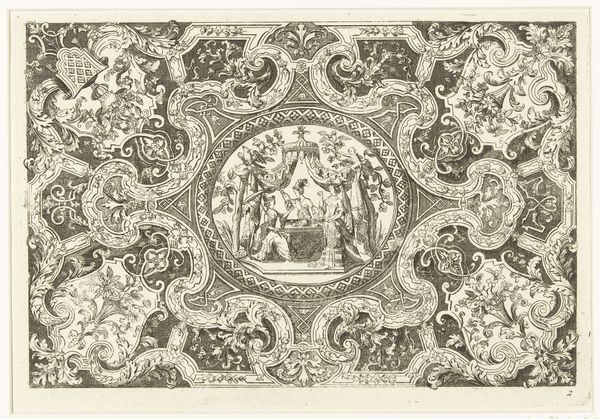

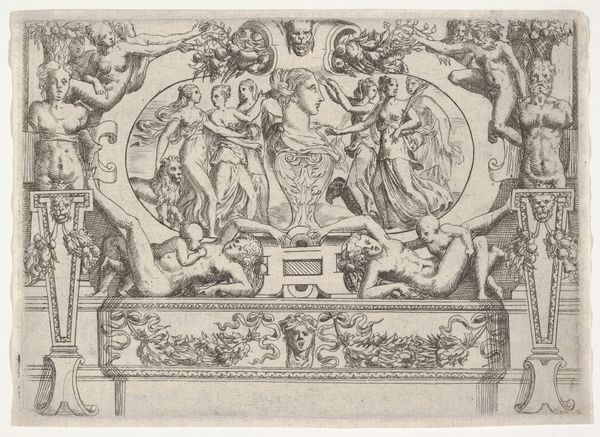

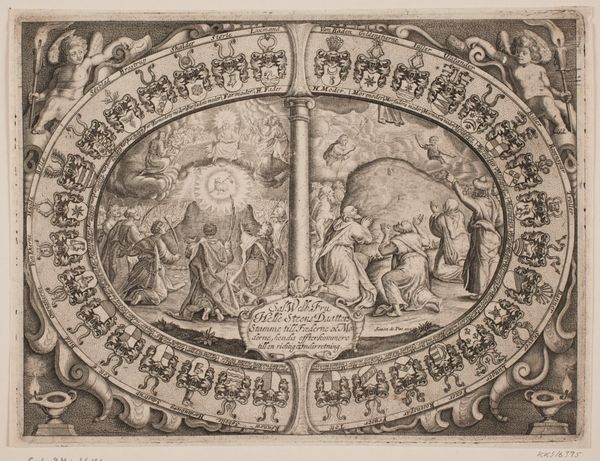

drawing, print, ink, engraving

#

drawing

#

allegory

#

pen drawing

# print

#

pen illustration

#

old engraving style

#

mannerism

#

figuration

#

ink line art

#

11_renaissance

#

ink

#

pen-ink sketch

#

line

#

pen work

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 88 mm, width 122 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: So, here we have Abraham de Bruyn's "Cartouche: Jupiter en Danaë," created around 1584. It's an ink engraving, full of such ornate details. There is a sense of density to it with a scene framed within a complex decorative border, complete with sea creatures, human figures, and garlands. What really strikes me is this almost overwhelming sense of… theatricality. What do you make of it? Curator: Theatricality is a key observation. This engraving operates within a highly self-conscious visual culture. Consider how prints at this time served not just as art objects, but as a crucial means of disseminating imagery and ideas. This particular piece, with its classical subject matter and Mannerist style, catered to a learned audience familiar with mythology. We must remember prints also acted as a form of currency. Can you imagine where one might encounter something like this? Editor: Perhaps in an aristocratic household? Somewhere that valued classical learning and displays of wealth? Curator: Precisely. Think about the power dynamics inherent in the depiction of Jupiter's seduction of Danaë. It speaks to issues of patronage, power, and the male gaze, wouldn't you say? This isn't just a neutral retelling of a myth, it reflects the socio-political climate of the time and was definitely designed to flatter someone’s world view and power. Editor: So it's not just art for art's sake. It’s loaded with the ideologies and power structures of the 16th century, which makes the art serve purposes other than display. I now look at the composition and layout differently; its ornamental framework has even greater symbolic weight. Curator: Exactly. And it compels us to think about who had access to such images, who commissioned them, and what messages they were meant to convey within a specific social and political context. These objects help reveal the history. Editor: It gives me so much to think about concerning the intersection of art, power and politics of representation in that era. I had no idea that I’d be entering the realm of the sociopolitical.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.