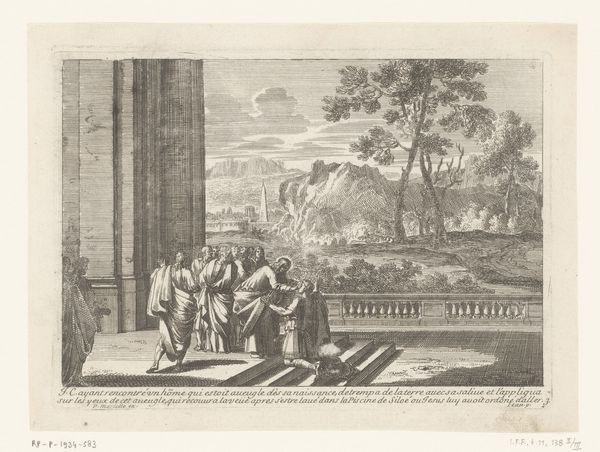

print, engraving

#

neoclacissism

#

narrative-art

# print

#

landscape

#

classicism

#

cityscape

#

history-painting

#

academic-art

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 148 mm, width 186 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This engraving, created around 1780 by Pietro Antonio Martini, is titled "Christus en de hoofdman van Kafarnaüm" or, in English, "Christ and the Centurion of Capernaum." The work exemplifies neoclassical aesthetics through its clear lines and classical architectural elements. What are your initial thoughts on this print? Editor: The cityscape depicted is striking. It certainly evokes a sense of historical weight, and I think Martini uses it to position the power dynamics at play in this narrative, with a crumbling classical architecture juxtaposed with signs of military presence and authority. There is a visual conversation around different systems of power at play here. Curator: Indeed, Martini employs precise engraving techniques to construct depth, which then emphasizes this dialogue between faith and authority. Notice the careful distribution of light and shadow—the lines accentuate the musculature of the figures, as well as the texture of the classical ruins. The formal clarity lends itself to understanding Martini’s technical prowess as well as his adherence to Neoclassical principles. Editor: While I can acknowledge the mastery of the technique, I'm more drawn to how Martini positions the figures within the historical and social hierarchies that structure the narrative. The centurion's act of kneeling, coupled with Christ's welcoming stance, feels intentionally designed to interrogate power. This narrative offers an allegory for resistance against colonial authority, as well, which then transcends the work beyond purely religious meaning-making. Curator: An interesting consideration. From a compositional point of view, however, I believe the balance achieved through the placement of figures against the ruins and cityscape leads the eye systematically, emphasizing the universality of the moment depicted, transcending a purely political read. It’s not about power specifically, but humility in the face of a divine moral code. Editor: Perhaps both readings can co-exist. By grounding the spiritual within tangible markers of social and political hierarchies, Martini makes us question not only faith, but the very power structures around it. It allows us to interrogate not just belief, but the conditions under which beliefs are perpetuated or contested. Curator: An engaging dialogue; thank you for contributing. Editor: It’s always a pleasure to consider how art acts as both a mirror and a catalyst for change.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.