print, photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

pictorialism

# print

#

impressionism

#

landscape

#

nature

#

photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

monochrome photography

#

naturalism

#

monochrome

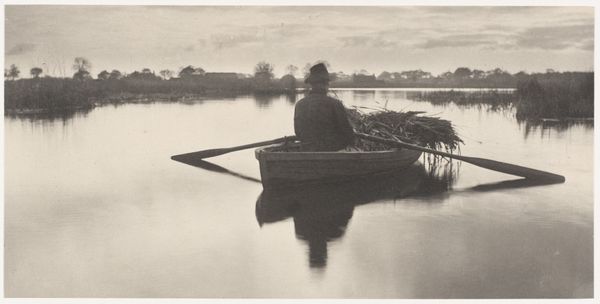

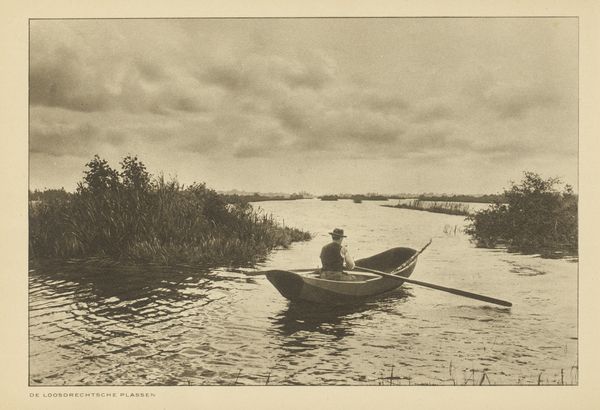

Dimensions: 20.3 × 28.9 cm (image/paper); 28.6 × 40.8 cm (album page)

Copyright: Public Domain

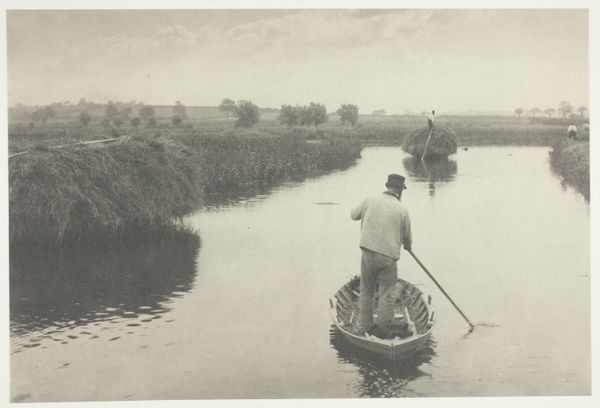

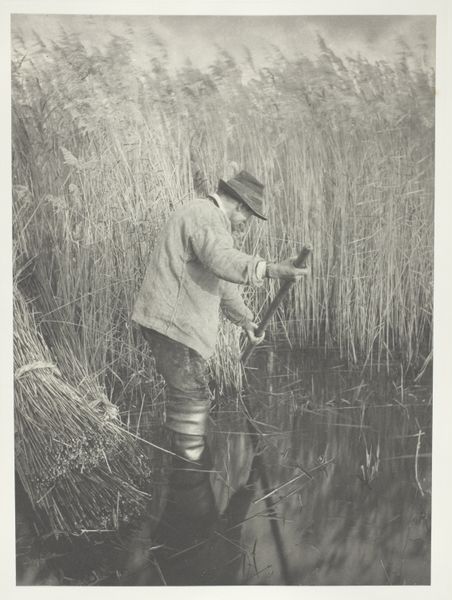

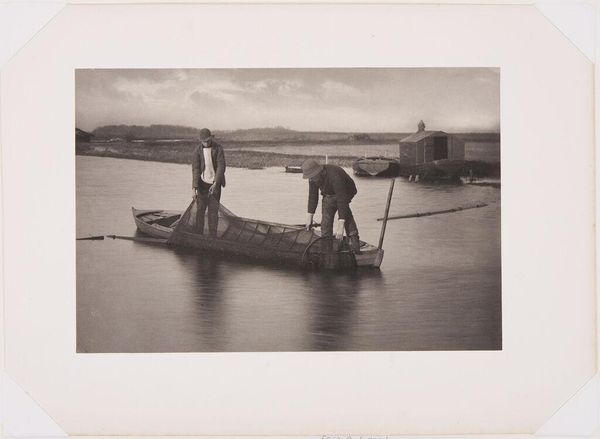

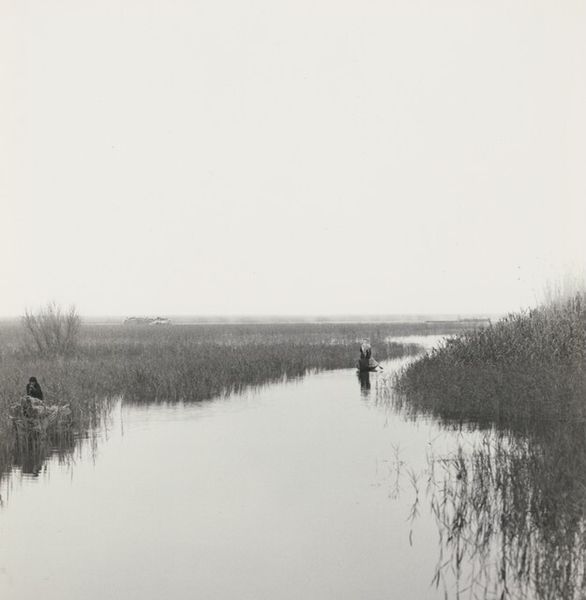

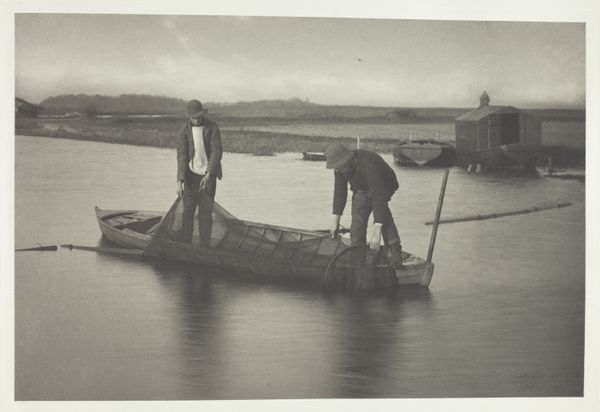

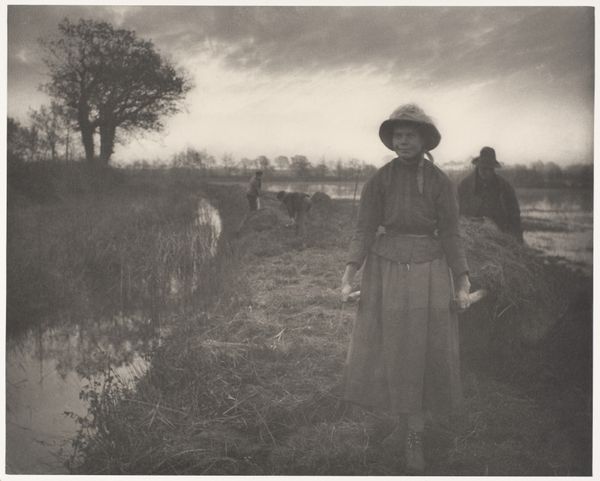

Editor: So, here we have Peter Henry Emerson's gelatin-silver print, "Marshman Going to Cut Schoof-Stuff," created in 1886 and now residing at the Art Institute of Chicago. It's undeniably melancholic, with all those muted tones. What historical elements can you glean from this particular image? Curator: Well, pictorially it’s evocative of its time. The photographic process itself, the gelatin silver print, emerged as a dominant medium then. But more than that, Emerson championed naturalistic photography as art. Think about the context: industrialization was booming, cities were growing, and artists like Emerson pushed back. He turned to rural landscapes and laborers, valorizing their way of life as the authentic ‘English’ experience that risked being displaced by modern development. What do you notice about the figure’s placement in relation to the landscape? Editor: He is facing the landscape with his back towards us. So, we look at the world with him. Curator: Precisely! And think about *who* had access to cameras at this point. Emerson's photography wasn't just art, but a statement about the perceived cultural hierarchies of the era, where the 'noble peasant' was juxtaposed against an urban elite. Photography like this fed into a national narrative – and who had control of that narrative? Was it the marshmen? Editor: No, probably those with the privilege to depict them. Did these photographs circulate widely, further shaping those perceptions? Curator: Absolutely. Exhibitions were crucial; magazines reproduced these images. The public consumed these romanticized visions, often unaware of the complexities of rural life or the potential for exploitation. So, the question isn’t just what does this photo show, but what did it *do*? Editor: So, it both documented and actively shaped the public's view. That changes my view on the artwork’s message, because it is also a sign of that time, with all of the inequalities involved in its own making and distribution. Curator: Exactly. These images can be beautiful, but they are not neutral.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.