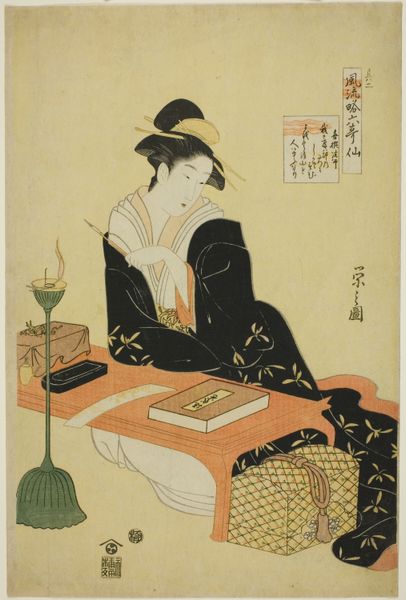

The Courtesan Hanaōgi of the Ōgiya Brothel (Ōgiya Hanaōgi), from the series Beauties of the Pleasure Quarters as Six Floral Immortals (Seirō bijin rokkasen) 1784 - 1804

0:00

0:00

#

portrait

# print

#

asian-art

#

caricature

#

ukiyo-e

Dimensions: Vertical ōban; Image: 14 9/16 × 9 7/8 in. (37 × 25.1 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

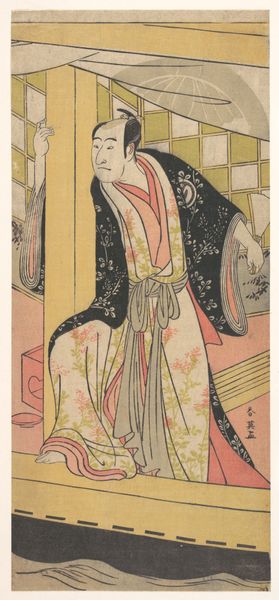

Curator: Before us is "The Courtesan Hanaogi of the Ogiya Brothel, from the series Beauties of the Pleasure Quarters as Six Floral Immortals", a captivating ukiyo-e print by Chobunsai Eishi, dating roughly between 1784 and 1804. Editor: The delicate lines and muted tones are immediately striking, it's quite a departure from the flashy courtesan images that first spring to mind with ukiyo-e. There's a quiet intimacy to this scene, almost melancholy. Curator: Indeed. This piece comes at a pivotal moment, representing the shift from the robust figures of earlier prints to more refined and elegant depictions. Eishi himself, a member of the samurai class, lends a unique perspective, perhaps influencing this sense of understated grace. Editor: That's interesting context, because I'm immediately drawn to the objects around her—the writing tools, the meticulously designed kimono. It highlights a sort of cultivated production involved in maintaining these images, the social roles being performed and consumed. The print itself as a commodity being essential here. Curator: Precisely. We must consider the courtesan's position within the pleasure quarters and Japanese society. This print isn't simply a portrait; it's a commentary on the idealized female image, deeply entangled with ideas of beauty, class, and societal expectations. Editor: Thinking of this in terms of the labor involved in its construction, even her posture as she holds that fan just so—a physical display of what it took to exist in this kind of system. It’s also intriguing that this piece survives today in the collections of institutions like the Metropolitan Museum. How does this change how it continues to circulate today, and how can we use this knowledge to promote responsible art-viewing habits today? Curator: Excellent point. The life of this image, its production, circulation, and eventual institutionalization speaks volumes. We have an example of a highly stylized and carefully crafted work that serves as a valuable cultural document through multiple eras and in multiple cultures. Editor: Looking at Hanaogi in our present-day context, the layers of history embedded in its materials force us to grapple with ethical concerns inherent to art consumption. How do we deal responsibly with an object reflecting a history that is quite complicated when held to contemporary cultural expectations and societal understanding? Curator: It’s a point of both attraction and repulsion that fuels debate, driving us to dissect social constructs of identity and womanhood, as presented here, that are constantly re-framed throughout history. Editor: Exactly! Let's allow it to facilitate a necessary reflection and reassessment about beauty, commodity, identity, and, even more broadly, representation itself.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.