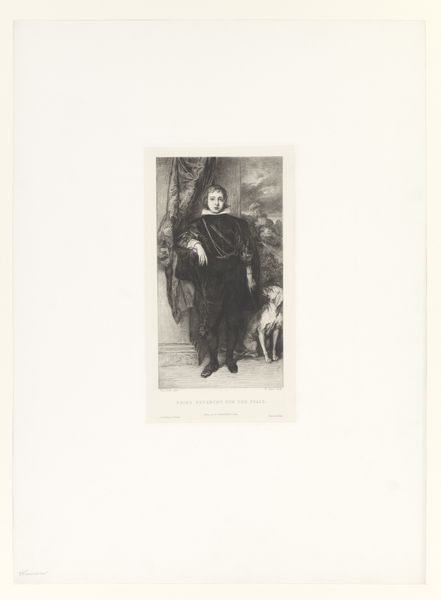

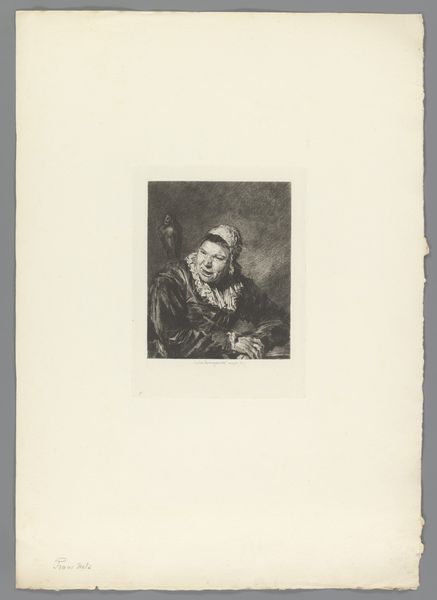

Dimensions: height 450 mm, width 310 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

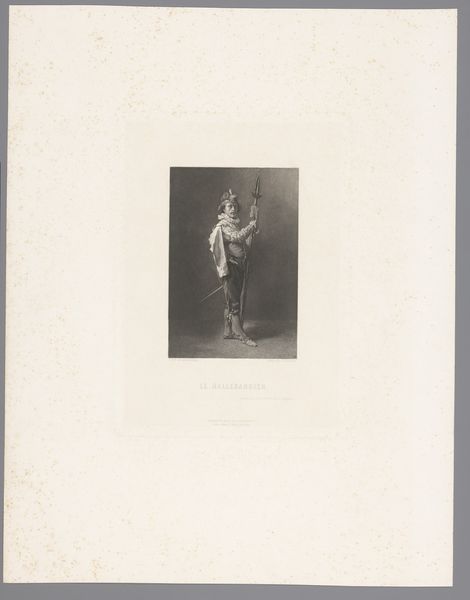

Editor: So, this is Frederik Hendrik Weissenbruch's "Pieter Florisse," an engraving made between 1858 and 1862. There’s a somber mood to it. I'm struck by the way Florisse is positioned, almost like a political portrait. How do you see this piece in its historical context? Curator: The Rijksmuseum holding this piece places it within a canon of Dutch history and identity. Think about it: in the mid-19th century, the Netherlands was actively constructing its national narrative. Representing historical figures like Pieter Florisse, a naval hero, reinforces that narrative. But what is communicated by producing this image using printmaking rather than painting? Editor: That's a good question. Maybe the artist wanted to emphasize Florisse's role for a broader public? Making prints is a more democratic method. It’s not just about wealthy patrons having access to it. Curator: Exactly! Prints have a distribution that paintings do not, speaking directly to a wider public and shaping historical consciousness. Now, how does the style of the engraving itself contribute? What era does it invoke? Editor: It seems reminiscent of the Baroque style. Is Weissenbruch perhaps connecting Florisse, and by extension, Dutch history, with a grander, almost heroic artistic past? Curator: Precisely. The “old engraving style” as tagged can evoke the perceived glories of the Dutch Golden Age. The placement of the ornate coat-of-arms supports such a notion. Editor: I didn't consider how consciously Weissenbruch might be aligning Florisse with a specific image of Dutch history through printmaking. Thanks for this historical understanding. Curator: And I see the power of this piece anew through your observation of the ‘democratic’ distribution printmaking provided.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.