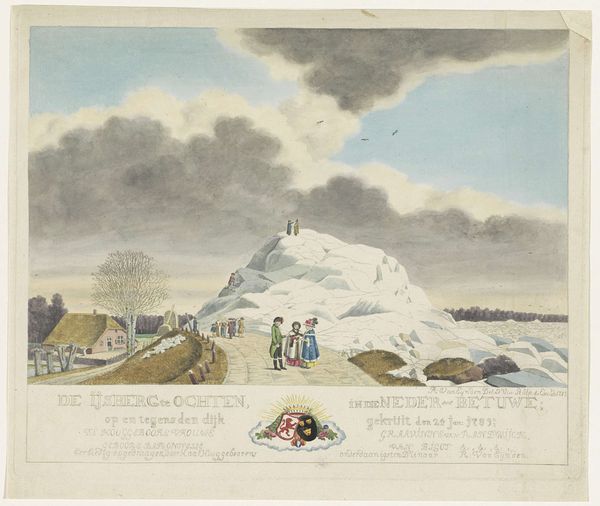

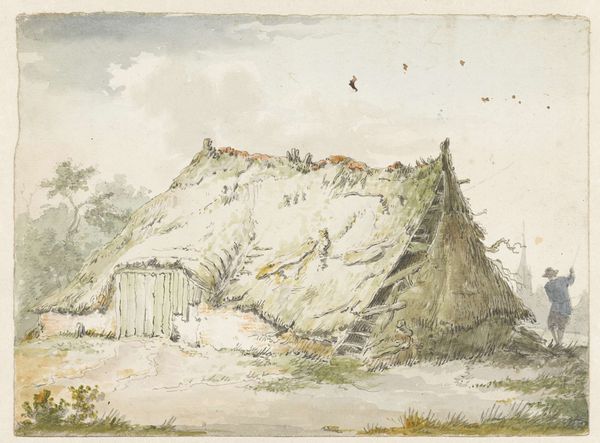

watercolor

#

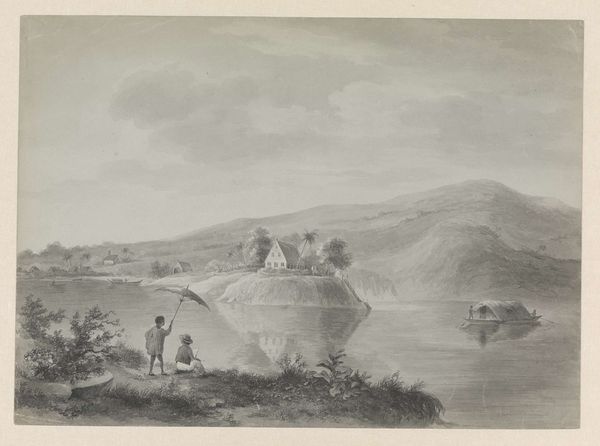

landscape

#

watercolor

#

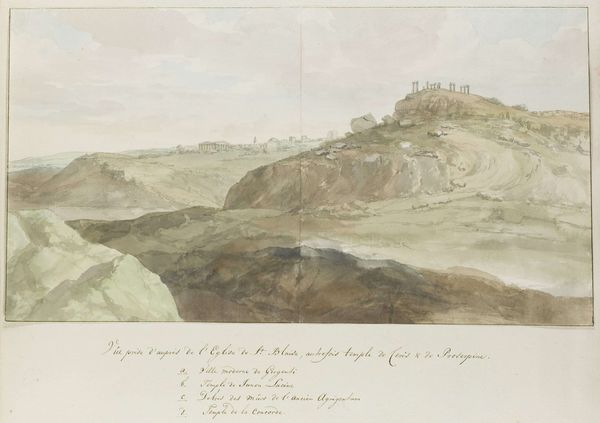

coloured pencil

#

romanticism

#

history-painting

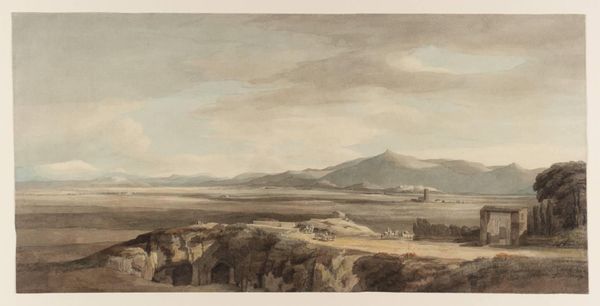

Dimensions: height 364 mm, width 501 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

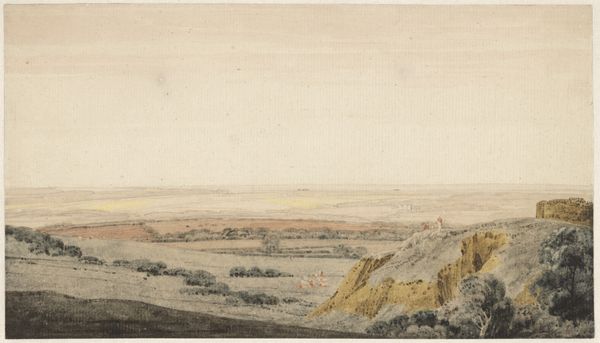

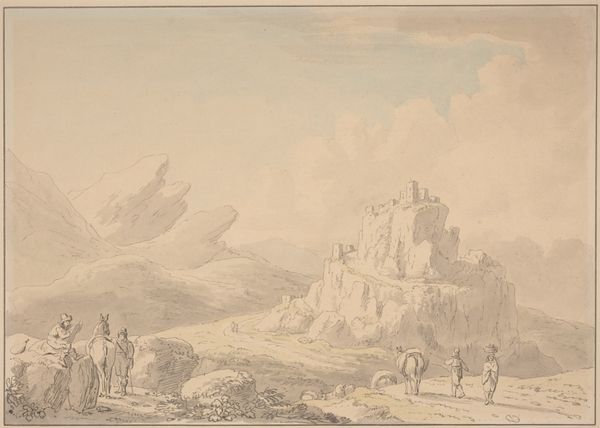

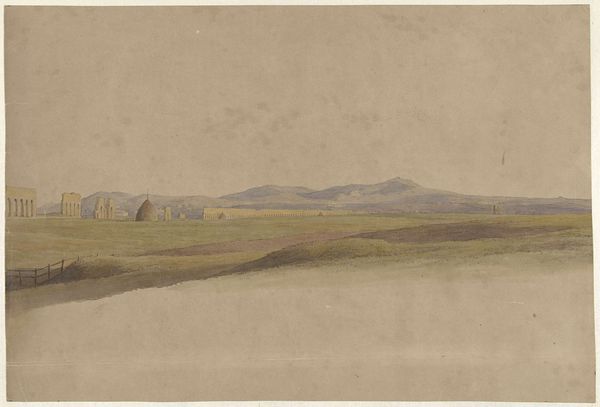

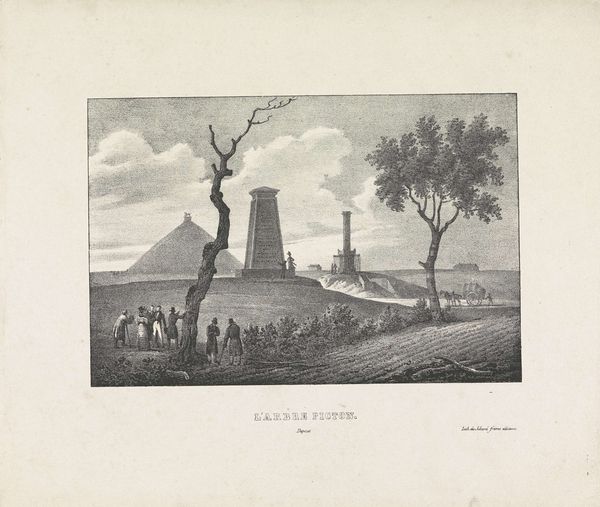

Editor: So, this is "Monumenten bij Waterloo, 1815," made between 1815 and 1820. It’s an anonymous watercolor at the Rijksmuseum. The scene has an air of tranquility about it, despite the historic battle. I wonder what purpose these monuments served, beyond remembrance. How do you interpret this work, especially considering its historical context? Curator: It’s interesting you picked up on that tension between peace and a battle site. Looking at this from a historian's viewpoint, these monuments, built shortly after Waterloo, were not just about remembrance. They are deeply embedded in the socio-political climate of the time. Consider the role of these structures in shaping the narrative of the battle. Were they symbols of victory, reconciliation, or perhaps, something else entirely? Think about who commissioned these monuments, and what message they wanted to send to the public. Editor: That's a great point, the act of commissioning shapes the narrative. It makes me wonder, who *did* commission them? And how did the everyday person view these monuments popping up on their landscape? Curator: Precisely! These monuments, while seemingly objective markers of history, are actually loaded with political meaning. The commissioning, design, and placement all contribute to a specific historical interpretation that favored certain political groups, mainly celebrating the victors and their ideologies. Do you think this perspective might shift our initial feeling of tranquility when considering what social purposes these monuments actually served? Editor: Absolutely! Framing it this way shows how even a seemingly peaceful landscape can be a site of cultural and political power. Seeing it less as a serene historical scene and more as a constructed narrative definitely changes things. Curator: Indeed. And by understanding the forces behind the image, the public function, and the politics of its creation, we get a far deeper appreciation. We reveal its subtle social operations by seeing how even images play into constructing ideologies, just like architecture does. Editor: Thanks, this conversation’s highlighted that sometimes art functions more as social architecture than artistic representation. I will remember this lesson.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.