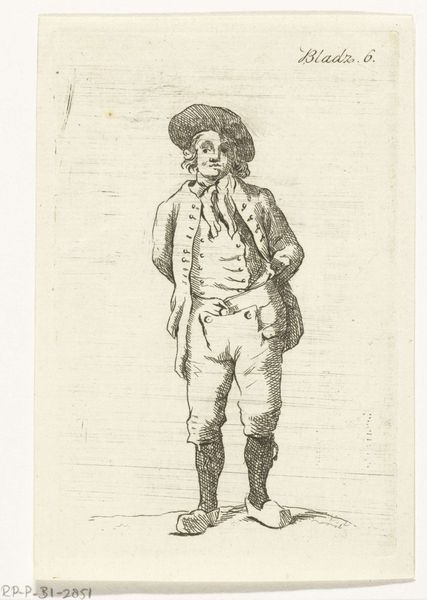

Dimensions: height 59 mm, width 40 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: This etching, *Marskramer*, which translates to 'Peddler' or 'Hawker,' is by Johann Andreas Benjamin Nothnagel and was created sometime between 1739 and 1804. It's deceptively simple, but I find myself wondering, what stories does this itinerant figure tell about the society he lived in? Curator: A crucial question. Consider the proliferation of such images in the 18th century. Why were these types—the peddler, the street vendor—so popular as subjects? Was it simply documentation, or did something deeper resonate with audiences? Editor: I imagine these images served as a sort of record, almost like a visual census. But why choose someone like a peddler, who exists outside of rigid societal structures? Curator: Exactly! The Baroque era, while valuing order, also held a fascination with those on the margins. Genre painting offered glimpses into the everyday, often romanticizing the lives of the working class while simultaneously reinforcing social hierarchies. The peddler, independent yet economically vulnerable, embodies this tension. Think about the role of these images within the context of an emerging merchant class and the rise of print culture, who would buy those and why. Editor: So, the image of the peddler could function as both a celebration of the common person and a subtle reminder of their place in the social order? It’s fascinating how loaded a seemingly straightforward depiction can be. Curator: Precisely. The circulation of images like this helped shape perceptions of class, labor, and the very fabric of society. And how those perceptions shape laws, tastes and overall socio-economical mobility. Editor: This has given me so much to think about. It’s easy to see art as just pretty pictures, but there's often a whole world of social and political meaning embedded within. Curator: Indeed. By questioning the artwork’s role within its cultural and historical moment, we reveal those hidden dimensions and gain a richer understanding of the past and the politics of the present.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.