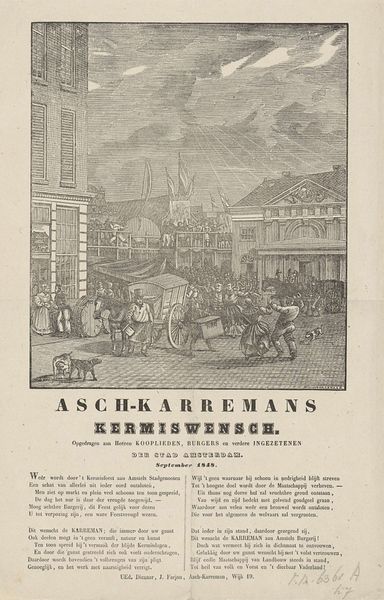

Nieuwjaarswens van de Amsterdamse askarrenmannen voor het jaar 1847 1846 - 1847

0:00

0:00

print, engraving

# print

#

cityscape

#

genre-painting

#

engraving

#

modernism

Dimensions: height 338 mm, width 225 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

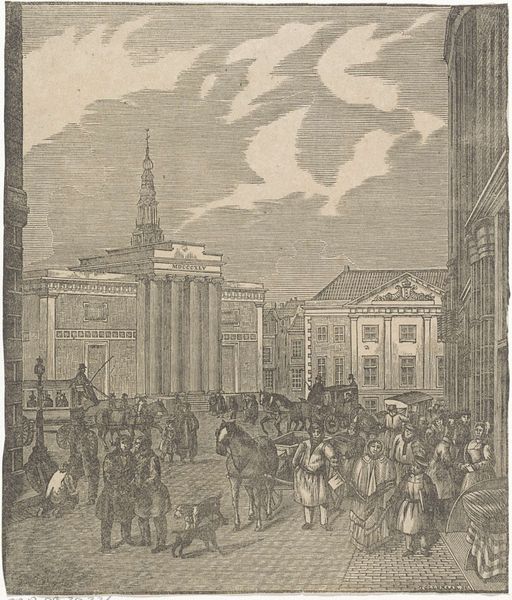

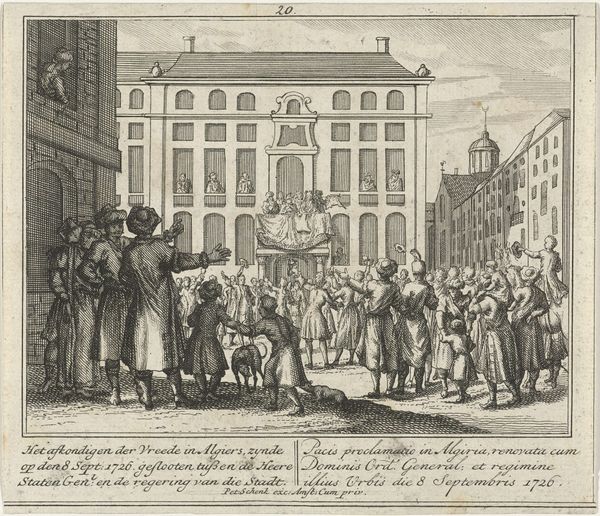

Curator: We're looking at "Nieuwjaarswens van de Amsterdamse askarrenmannen voor het jaar 1847," or "New Year's Greetings from the Amsterdam Ash Cart Men for the Year 1847." Dirk Wijbrand Tollenaar created this print somewhere between 1846 and 1847. Editor: It’s rather bleak. The starkness of the monochrome engraving and the crowded cityscape convey a certain melancholy. There's a palpable density in the application of the lines and the construction of perspective. Curator: Exactly. And yet, there's a layered approach to materiality in this work. Tollenaar wasn't merely making an image; he was creating an object embedded in a specific economic and social transaction. Ash cart men presented this engraving to their patrons as a New Year's greeting, perhaps expecting a gratuity. It's work manifesting as printed matter. Editor: The subject matter reinforces that understanding of labor. Look at how the architecture and street activity create planes; there is attention being paid to form in the perspective and rendering of structures. The contrast in architectural rendering, figures and landscape points to modernist interpretation. But how might the context of its creation and function play into a modernist assessment of this print? Curator: The image reflects that material reality. While seemingly a simple city scene, it contains an entire economic relationship. Consider how printmaking democratized image production, extending it to artisans. In those processes and means, lies the cultural work! Editor: The inclusion of verse below the image adds another layer of social commentary and highlights of class structures with respect to "kooplieden, burgers en verdere ingezetenen der stad Amsterdam"– "merchants, citizens, and other inhabitants of the city of Amsterdam." This feels deeply embedded in place and production. The physical handling of materials and the exchange for that physical thing connects these workers to city commerce in 1847. Curator: I see what you’re getting at. Perhaps this is a self-conscious form reflecting that economic relationship and giving the workers a way to literally stamp their existence in the city. The very material of this print is both the means of their appeal and their legacy. Editor: Precisely. Seeing it that way alters one's perception; the labor is permanently embedded in its form and texture, connecting art directly with societal context. Curator: Yes, examining it this way gives dimension beyond mere aesthetic arrangement. It's the relationship, really, between creation, circulation, and society.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.