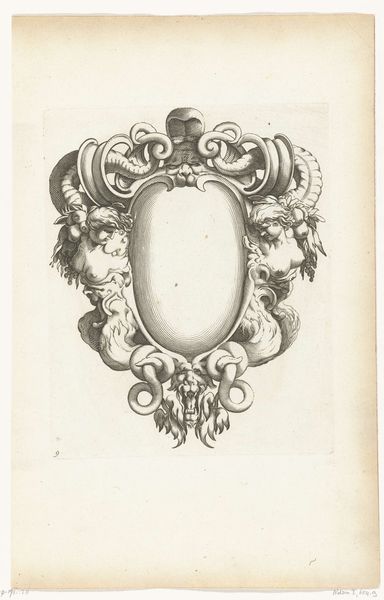

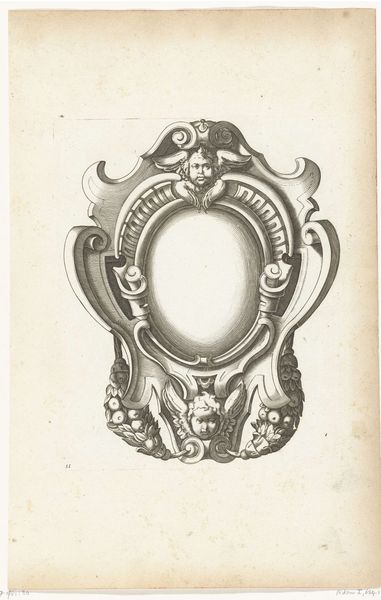

drawing, print, engraving

#

drawing

#

baroque

#

pen drawing

# print

#

form

#

line

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 184 mm, width 154 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

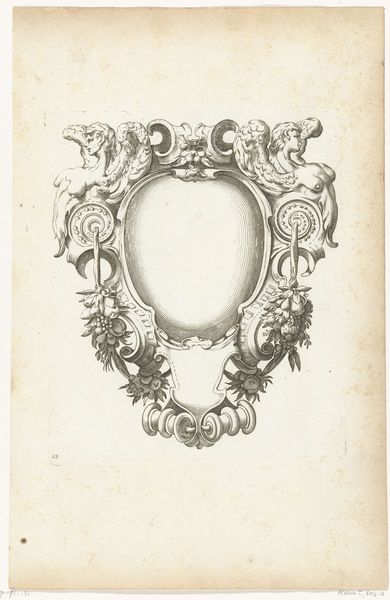

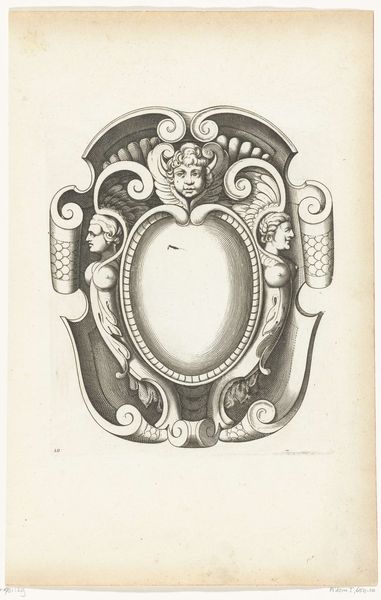

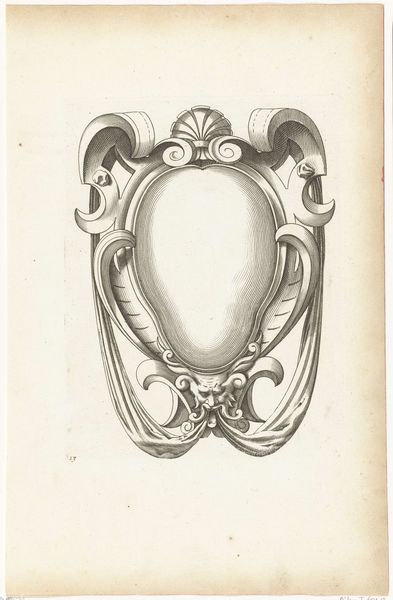

Curator: Let’s spend a few moments with H. Picart’s “Cartouche met cherubijntje en gevleugelde vrouwen,” created around 1628. It's an engraving, showcasing incredibly fine lines. What's your immediate impression? Editor: Elegantly morbid, wouldn’t you say? It’s baroque—all swoops and curls—yet something about the stern faces clinging to the oval makes me think of memorial art. Like a frame awaiting a dearly departed portrait. Curator: I love that! It’s like the Baroque’s flair for drama channeled into a very specific, decorative purpose. These cartouches were essentially ornate picture frames. This one beautifully demonstrates the engraver's skill in mimicking the textures and three-dimensionality of sculpture with nothing but ink. Editor: Exactly. But it is also very much a product. Look at the repetition, the way the winged figures echo each other. This was made for mass production, each print a replica meant for widespread distribution. Think about the labor involved, the time, the skill. It collapses the idea of "high art" a bit, doesn’t it? This craft was as important as any painting back then. Curator: I agree completely. It reminds me of old, exquisitely wrought invitations or personalized stationery, almost like a precursor to those objects. There's something deeply romantic about that accessibility, the potential for this very grand style to enter ordinary life. I wonder, what portraits might have been placed within this ornate frame? Editor: Or think of the artisans crafting these. The paper itself, likely handmade; the ink, carefully formulated. It’s easy to forget the sheer physicality that precedes even the most 'refined' art. I keep wanting to trace the route of the copper itself – did Picart mine it? Who smithed the printing press? All the work embodied to distribute his design. Curator: Considering all the resources – literal earth and bodies– involved shifts how we see the image, doesn't it? I think I look at that central space differently, now. Knowing the invisible supports of its production… almost imbues it with another presence entirely. Editor: Well put. Next time I see Baroque art, I'll remember all the skilled workers, often unnamed, whose hands shaped its opulent excesses. It makes me feel like I'm honoring something hidden, like a whispered acknowledgement.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.