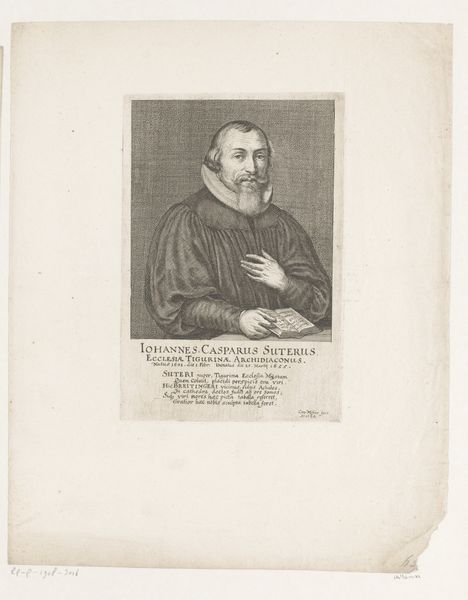

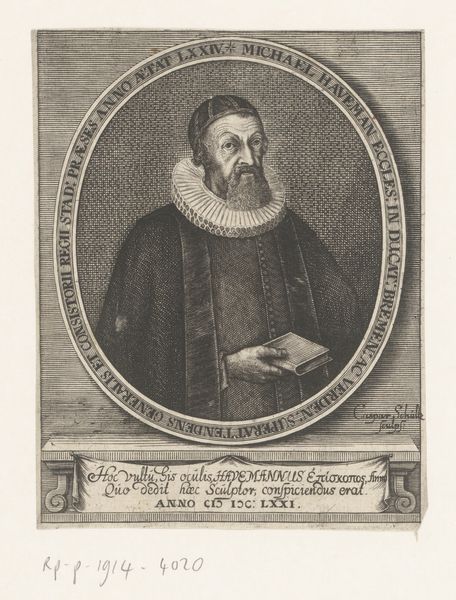

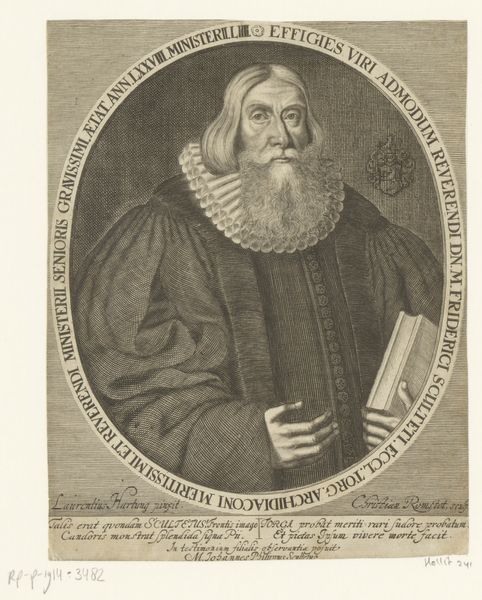

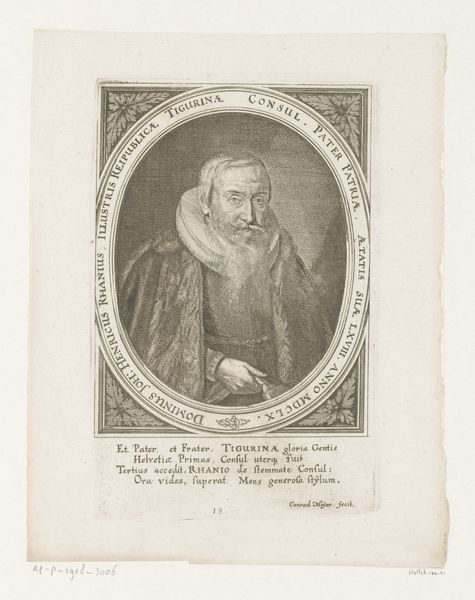

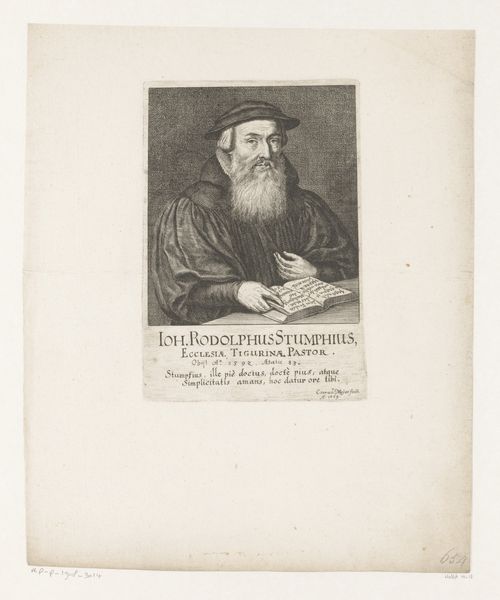

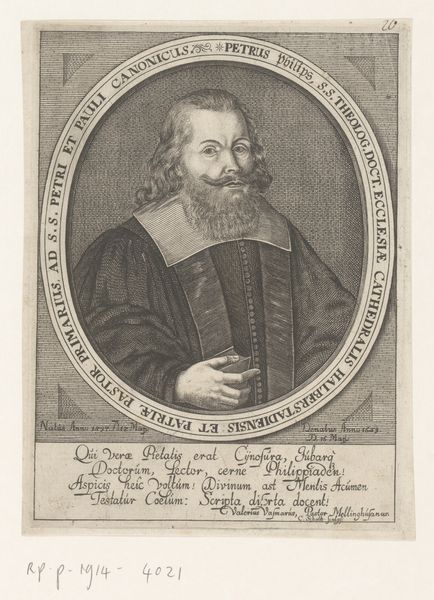

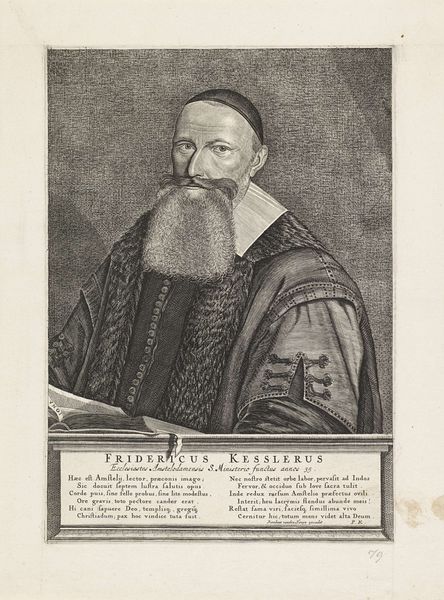

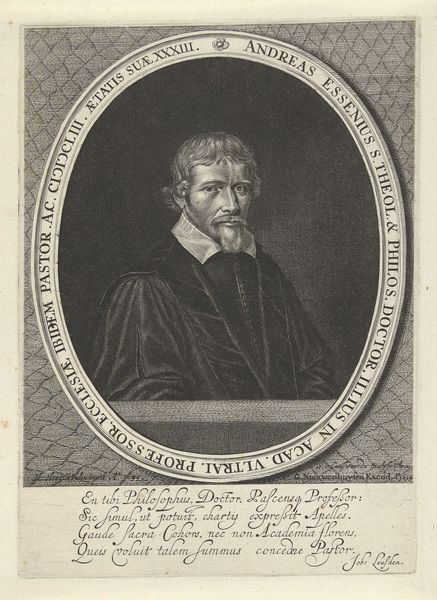

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

aged paper

#

baroque

# print

#

old engraving style

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 150 mm, width 98 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

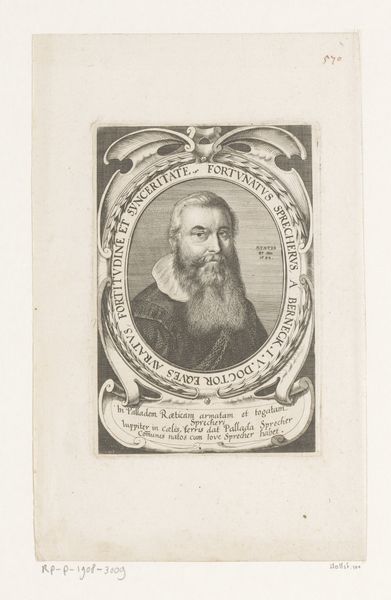

Editor: This is a rather striking engraving entitled "Portret van Fortunat Sprecher von Bernegg," created in 1748 by David Herrliberger. The detail achieved through the engraving technique is incredible; the man’s beard seems to have real depth. What kind of cultural context do you see informing this work? Curator: Well, considering Herrliberger’s place in 18th century Zurich, this print reflects the rise of civic identity being visually represented through portraiture. Printmaking enabled the wider dissemination of these images, thereby crafting a more public persona for figures like Sprecher. Did he commission this or was it an independent publishing venture? Editor: That's a good question, and something I should have considered! From what I've read, Herrliberger produced a large volume of prints of notable figures. It seems less about individual commission and more about creating a visual archive of influential citizens for public consumption. Curator: Exactly. Notice how the inscription beneath the portrait identifies Sprecher as a military leader ("bellicarum Praefectus") and highlights his associations ("Rhatus, Eques")—titles that connect him to powerful networks. The portrait isn't just about individual likeness but signaling membership and power within specific social structures. Think about the intended audience for such prints; how might they interpret these visual cues? Editor: I guess that ordinary citizens of Zurich seeing this would feel a stronger connection to these figures, as the prints helped create a visual connection between those with power and the people that they governed. And because print was accessible, it played a large part in building this connection. I hadn't really considered the role of art as a social connector in this context. Curator: Precisely. Prints such as this acted as social and political currency in the 18th century, which really gives a totally new lens through which to analyze portraiture like this one. Editor: Thanks, this has given me a totally new perspective on the purpose of portraiture at this time.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.