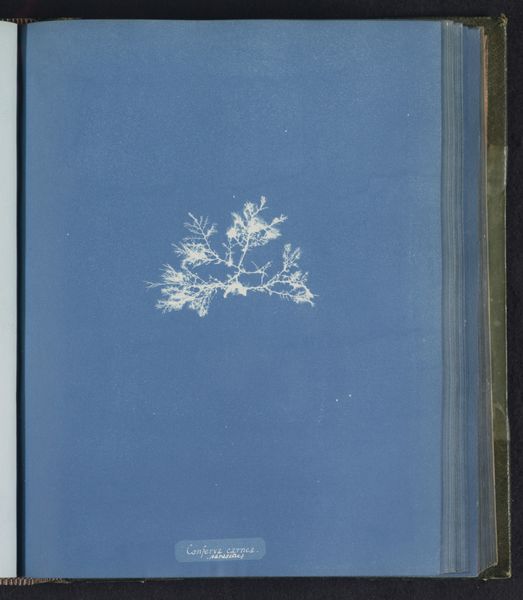

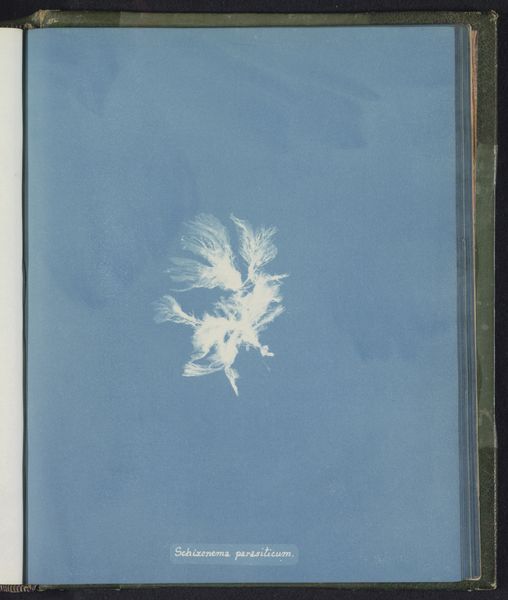

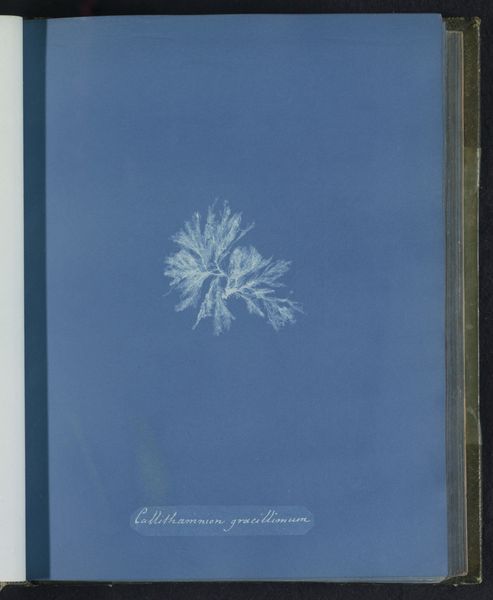

![Schizonema Smithii [= Schizonema smithii] by Anna Atkins](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fd2w8kbdekdi1gv.cloudfront.net%2FeyJidWNrZXQiOiAiYXJ0ZXJhLWltYWdlcy1idWNrZXQiLCAia2V5IjogImFydHdvcmtzLzNlMDVjYWYwLTdhM2MtNDU5ZC1hZmM3LWM3M2YzZWJlNzU0Mi8zZTA1Y2FmMC03YTNjLTQ1OWQtYWZjNy1jNzNmM2ViZTc1NDJfZnVsbC5qcGciLCAiZWRpdHMiOiB7InJlc2l6ZSI6IHsid2lkdGgiOiAxOTIwLCAiaGVpZ2h0IjogMTkyMCwgImZpdCI6ICJpbnNpZGUifX19&w=3840&q=75)

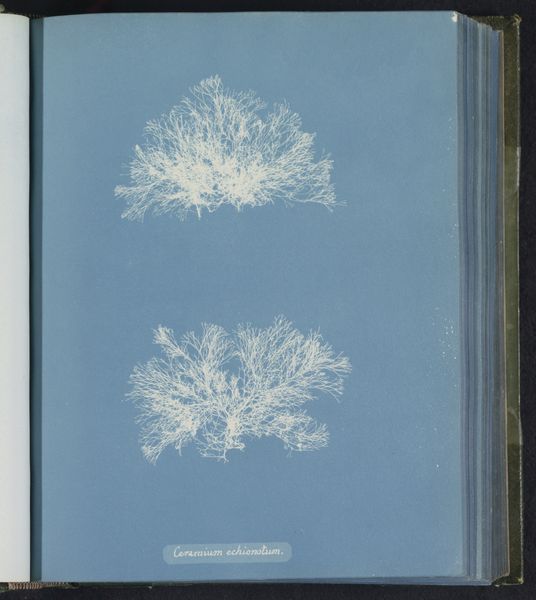

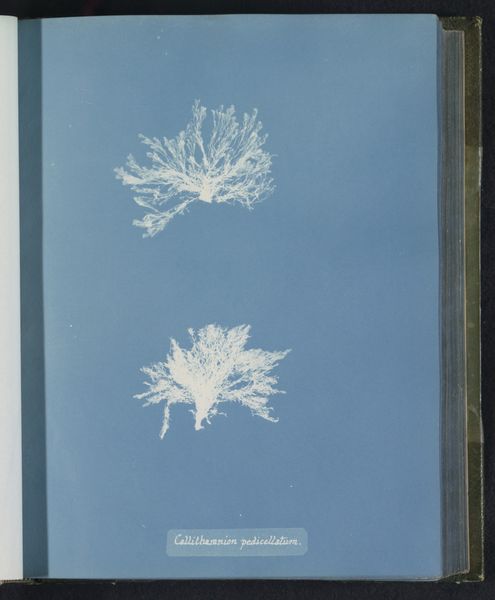

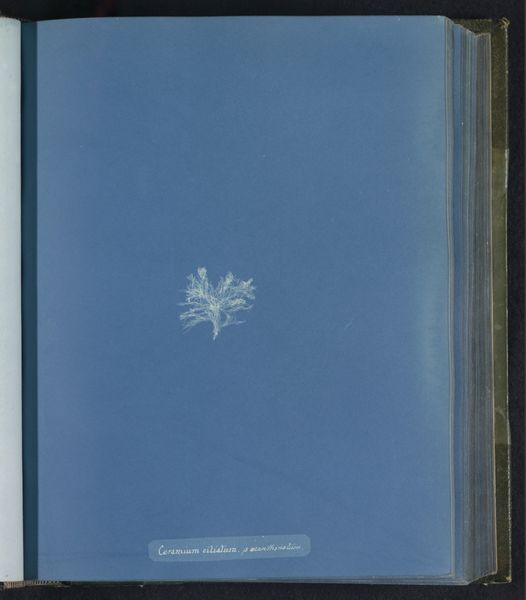

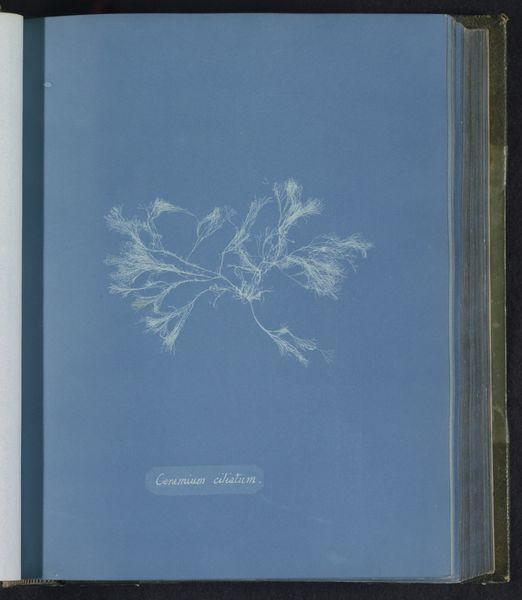

print, cyanotype, photography

# print

#

cyanotype

#

photography

Dimensions: height 250 mm, width 200 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: What a striking blue! I’m immediately drawn to the depth of that colour. Editor: That’s Anna Atkins’s “Schizonema Smithii [= Schizonema smithii],” made sometime between 1843 and 1853. What you're seeing is a cyanotype, a very early photographic process. Curator: So, more of a scientific illustration than an artistic endeavor, initially perhaps? It feels like an x-ray—there's this delicate form presented almost clinically, yet the vivid blue introduces such an unexpected element of emotion. The shapes themselves feel like a kind of primal diagram—seeds of life on a vast cosmic ground. Editor: Not so fast with the clinical assessment. The cyanotype process itself, using iron salts and sunlight, highlights human intervention and engagement with the material world. The creation of these images depended entirely on access to the right chemicals, the right equipment for processing them. Think about it - this work democratized the scientific image-making process. Curator: I see your point. Yet the decision to render it this way also speaks volumes. It evokes, for me, something of an early cosmos, echoing those hand-drawn star charts trying to map meaning and purpose onto the dark, the great unknown. The choice of algae—humble, yet vital—places an emphasis on the building blocks of the ecosystem, or, as it might've been read then, the "chain of being." Editor: Exactly. It reveals the means of production. Cyanotypes became an accessible tool, and in Atkins's hands, the boundary between scientific documentation and artistic representation became blurred, just as craft can blend into high art. It allows a unique form of knowledge-sharing outside traditional routes. Curator: A truly interesting perspective. The "blueprinting" or photochemical development, in that light, isn't simply a process but becomes a sign in and of itself, alluding to future advancements, as an emblem of what may grow from the raw potential held within this form. It shows, really, how our very conception of symbolic life is constantly shaped by technology and industry. Editor: It forces us to consider who had access to scientific discourse and knowledge at that time, and it's rewarding to contemplate Atkins's method, to observe how that may have served her well in breaking those cultural and gendered codes.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.