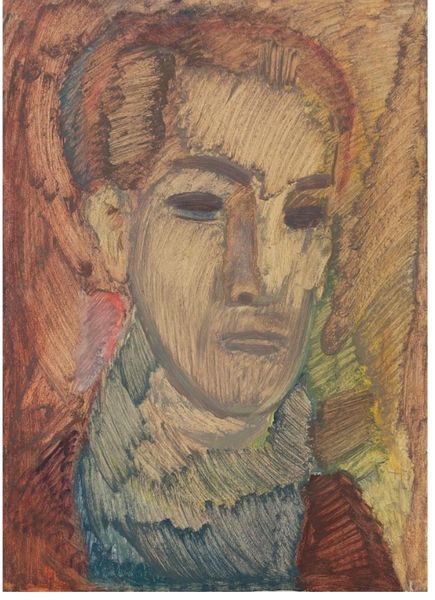

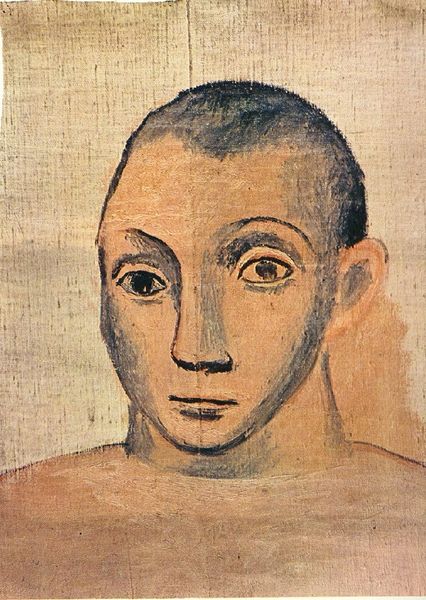

Dimensions: 52 x 98.5 cm

Copyright: Public domain

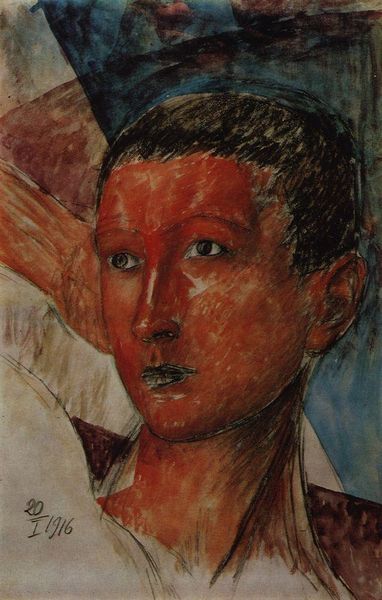

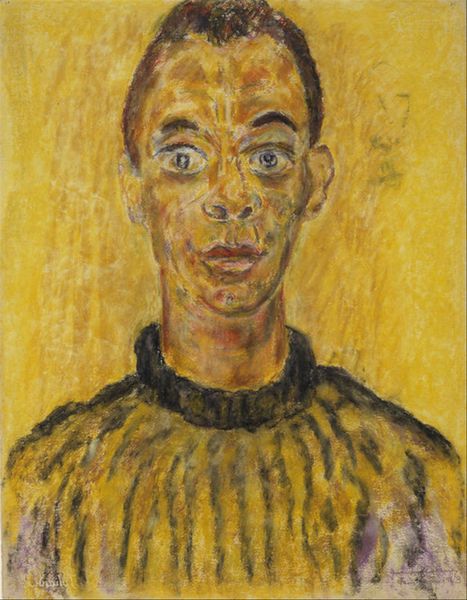

Curator: Here we have Kazimir Malevich's "Portrait of a Youth," painted in 1933 using oil paint. The subject stares directly outward, his hands held in an intriguing gesture. Editor: It strikes me as unsettling. The rawness of the brushstrokes, the almost sickly palette, especially that hint of green on the shaved head—it's all so unsettling, bordering on disturbing. Curator: Absolutely. And context is critical. This portrait was created during a period of intense pressure for artists in the Soviet Union under Stalin. Socialist Realism was becoming the only accepted style. Malevich, who had pioneered Suprematism, was forced to return to figuration. Editor: So, this unsettling mood—you’re saying it’s potentially reflective of the suppression he was facing as an artist, a maker forced to abandon his own language? The crude materiality becomes an assertion, a physical record of his compromised position? Curator: Precisely. Think about Malevich’s earlier, purely abstract works—their radical freedom. Then consider this portrait, burdened with representation, and arguably conformity, it tells a different story. We might even read the youth's gaze as an act of defiance, or at the very least, stoicism, under oppressive circumstances. Editor: And the hands? They seem to almost obscure the striped garment, a visual barrier perhaps. There's something unresolved in the making here; is he actively pushing back against the expected modes of artistic production with every deliberate, visible brushstroke? The materiality and making processes on view almost undermine the figuration itself. Curator: Exactly! Malevich’s embrace of expressionism here underscores the emotional weight of his predicament. This is not simply a portrait; it's a potent commentary on artistic and political constraints. Consider what it meant for someone so deeply invested in pure abstraction to return to such traditional form under coercion. Editor: Thinking about his turn back to figuration in light of what he had pioneered gives you a new way to look at how creative expression exists when constrained. Thank you. Curator: My pleasure. I find that approaching this piece through a gendered lens also adds valuable nuance to it, since so many women artists from similar timelines faced identical constraints, but their stories often receive little critical appreciation.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.