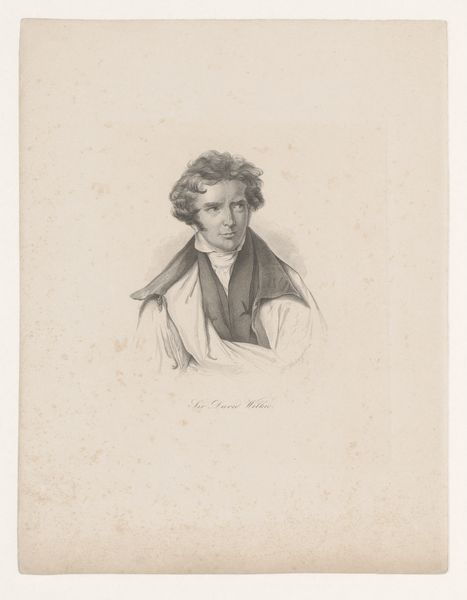

drawing, pencil

#

pencil drawn

#

drawing

#

romanticism

#

pencil

#

realism

Dimensions: height 192 mm, width 126 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

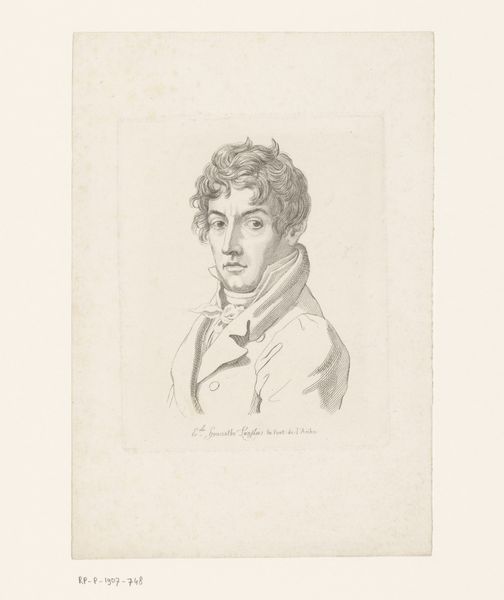

Curator: This work presents a rather striking air. It is called “Portret van Robert Mount, boekbinder en prentverkoper te Londen” – or, “Portrait of Robert Mount, Bookbinder and Print Seller in London.” We believe it was crafted sometime between 1800 and 1850. It’s a pencil drawing by an anonymous artist. Editor: The muted tones and the man’s serious expression do create a contemplative mood. It reminds us that image-making was a crucial mechanism to negotiate social position in the 19th century, whether one was a print seller or the member of the peerage whose portrait he would sell. Curator: Exactly. The image exists within a larger ecosystem of cultural production and consumption. Mount, as both a bookbinder and print seller, occupied a unique position in that system. He both created and distributed knowledge and art. This portrait thus acts as a window into understanding that complex network of print culture and the way in which a "middle-class" identity developed during the period. Editor: You see that represented, in particular, by the secondary imagery: the plaque held by a cherub, positioned below the portrait of Mount himself. We should be looking at what is written on the tablet there, and what books flank its side! We might also consider the social implication of using such imagery—drawing from classical tropes to elevate the individual’s character. Curator: And it really makes you wonder who commissioned it and for what purpose. The romantic and realism stylistic tags remind us of that tense duality from this time, particularly for those in emerging professional classes negotiating status and authority through visual culture. We must ask, for whom was it intended? Did it become part of Mount's professional life? Editor: Yes, such visual culture certainly became integrated into various modes of discourse, whether it be social, political or personal. But the subtle blurring of lines within those power dynamics allows the portrait, such as this drawing, to challenge the prevailing norms and narratives embedded in visual production and interpretation. The role of art in constructing those narratives becomes highlighted here. Curator: A fitting thought. It leaves me considering the portrait’s layered engagement with the public role of imagery at this transitional moment for England, the beginning of an industrialized modernity.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.