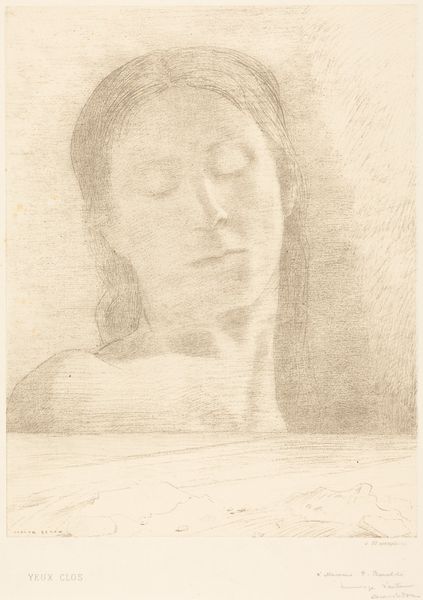

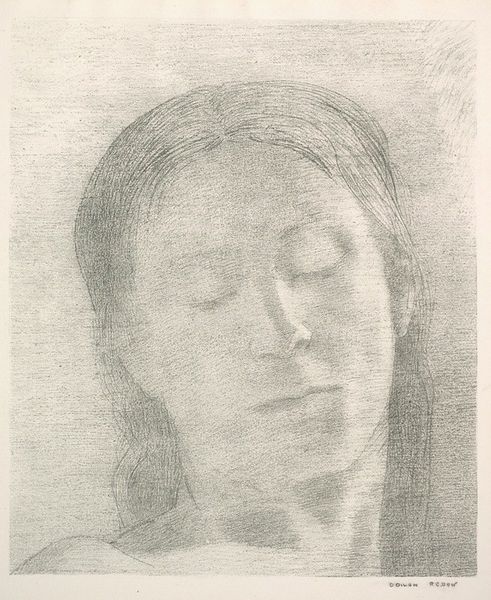

drawing, pencil

#

portrait

#

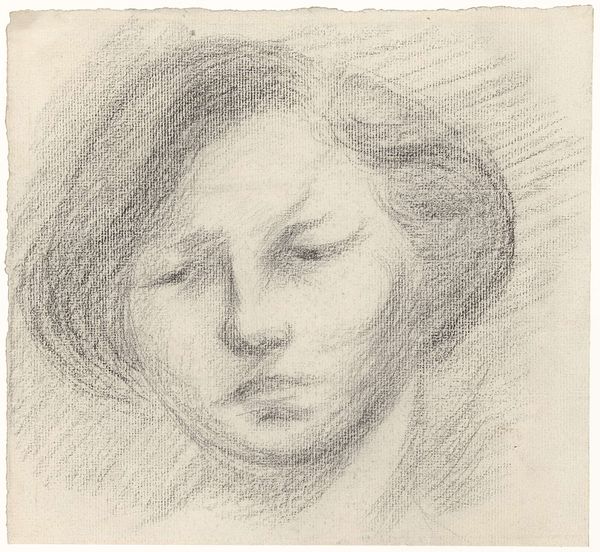

drawing

#

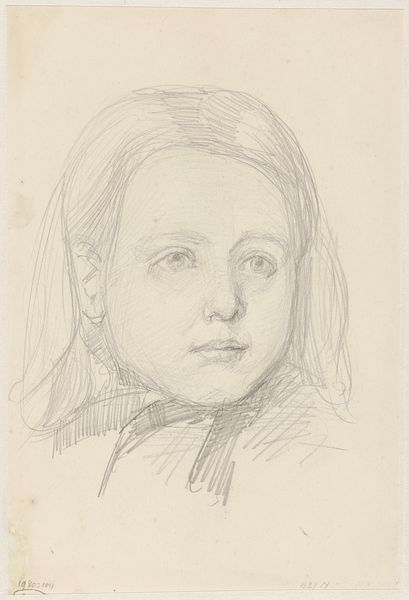

pencil drawing

#

pencil

#

symbolism

#

realism

Dimensions: 242 mm (height) x 188 mm (width) (bladmaal)

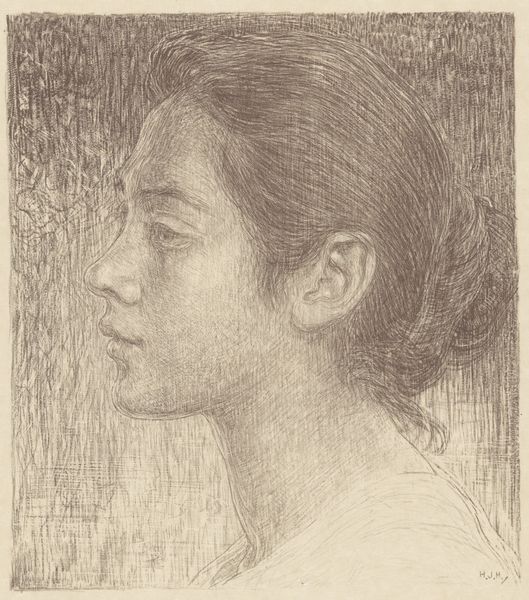

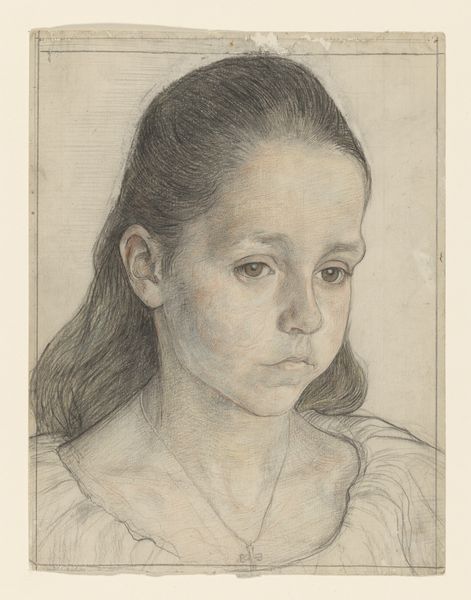

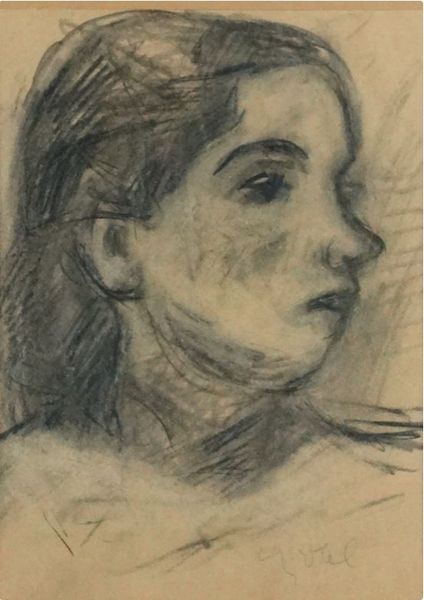

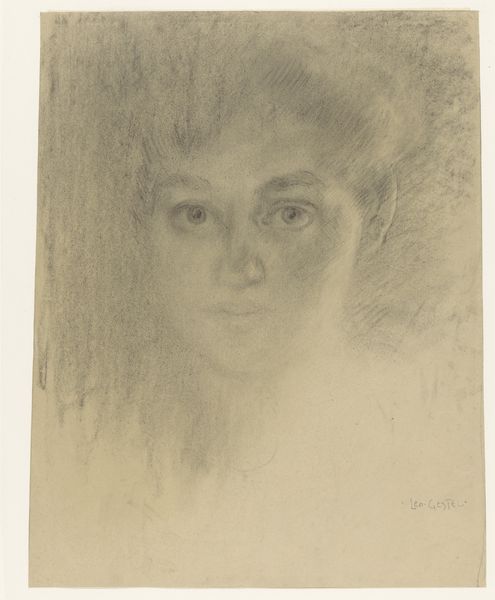

Vilhelm Hammershøi created this intimate graphite portrait of his wife, Ida, sometime during his career. Hammershøi lived during a time of shifting societal expectations, especially for women. Ida's identity is central to understanding this work. As his wife, she was a frequent subject, often depicted in domestic interiors, performing mundane, quiet tasks. Here, she is presented with her gaze lowered, an introspective pose that was typical of the artist. Is she an active subject or a passive object? The subtlety of the drawing underscores the quiet, interior life that was so valued in the bourgeois experience. Yet, there is also a sense of melancholy, perhaps reflecting the limitations placed on women during this period. The artist has captured a sense of personal reflection, but we are left to wonder if it’s one of contentment, resignation, or muted rebellion.

Comments

statensmuseumforkunst about 2 years ago

⋮

Vilhelm Hammershøi and his wife lived in various European cities with irregular intervals. The settlement in London For example, they lived in London from the end of October 1897 to the end of May 1898. Unlike Rome and Paris, London was not a capital of the arts at the time, and this naturally occasioned some surprise and speculation as to what made a Danish artist want to go there. James Abbott McNeil Whistler One of the reasons was, undoubtedly, the US-born painter James Abbott McNeill Whistler (1834-1903). In London Hammershøi took a step that was quite out of character. He wrote to Whistler and tried to meet him in person, but did not succeed. The main reason for this direct approach was that Hammershøi hoped for Whistler’s intervention to secure his representation at The International Society’s inaugural exhibition in 1898. Here, he wished to present Two Figures, a picture of himself and his wife, Ida, based on several studies such as this piece. A rendition of veiled presence The artist did not intend his picture to contain "portraits in the strictest sense of the word", and indeed this drawing is something other and more than a good likeness: a rendition of veiled presence, a pencil painting with echoes of Leonardo. Another obvious source of inspiration is the museum’s portrait of a young woman with a carnation, previously attributed to Rembrandt, but now attributed to Willem Drost (1633-58). Hammershøi painted a replica of this picture ten years before.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.