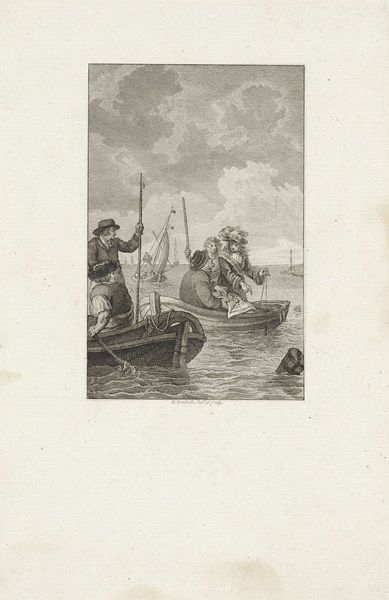

Dimensions: height 215 mm, width 145 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

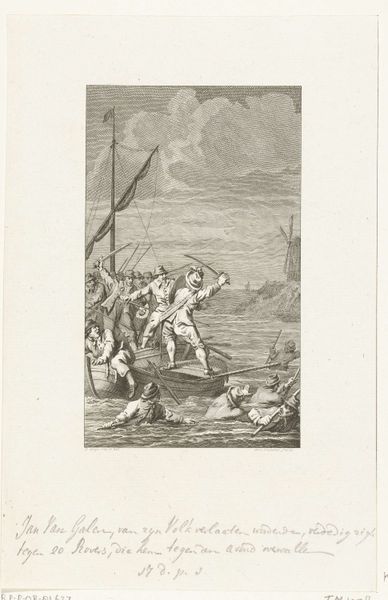

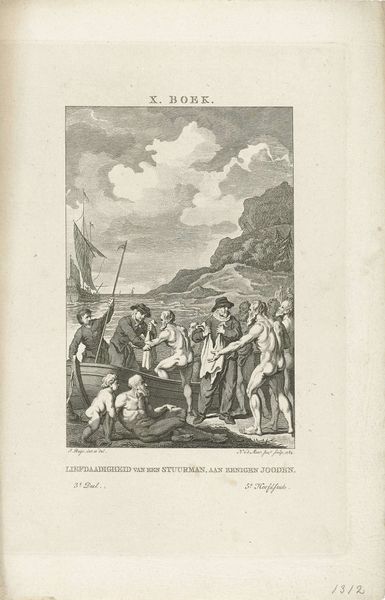

Curator: Immediately, I'm struck by the energy. The choppy water, the figures in motion, the sharp contrasts—it has a kind of Baroque drama despite the limited grayscale palette of the engraving. Editor: This engraving depicts the "Meeting of Adriaan van der Kam with Algerians, 1755". Created around 1829 by Philippus Velijn, it's a line engraving printed here, housed at the Rijksmuseum, drawing on a historical event but made decades later. Curator: Right, a reproduction intended for circulation perhaps. I'm drawn to the figures—are they genuinely being rescued or is there an implied power dynamic? I see the formal dress of Van der Kam contrasts sharply with those he's supposedly "saving". Editor: That contrast is key. Contextually, such images served specific ideological functions, especially concerning Dutch colonialism. The labor of producing such images – the engraver, the publisher – reinforces existing social structures, circulating power narratives regarding the "civilizing mission" through mass-produced art. How complicit are these productions in historical narratives? Curator: I agree, especially when it becomes such an easily reproducible and shareable image. But let's focus on the material process here. The linear precision achieved through engraving speaks to the craftsman’s skill; transferring intricate details, building tone, from original artwork to metal plate, a skill honed through intense manual labor, for wide scale reproductions. Editor: But it is so easily co-opted by oppressive, historical views on non-Europeans. I'm particularly sensitive to how this image contributes to constructing Algerians as perpetually in need of Western assistance, therefore perpetuating the narratives of cultural and economic dependence. Curator: It raises the question, what did people consume? Engravings like these weren’t passively received. Looking at the materiality and accessibility of this artwork—the conditions of production, circulation, consumption—allows us to gauge this cultural climate, how prevalent such images may have been, who engaged with them, to what extent it altered views on international politics, and if that awareness allowed for dissent? Editor: It prompts questions, definitely. Velijn's rendering allows a glimpse into 19th-century attitudes, the creation of art to bolster colonial justification. It reminds me that aesthetics aren’t neutral, even when translated through the meticulous craft of engraving. Curator: Yes. In that regard, this reproduction is a time capsule in many senses. Editor: Exactly. I'll never look at a simple engraving the same way again.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.