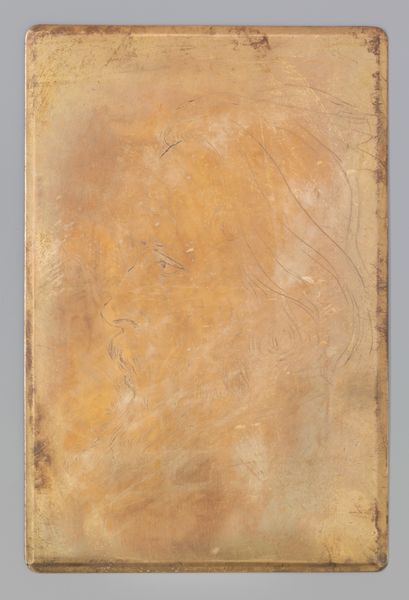

drawing, print, etching

#

drawing

#

neoclacissism

# print

#

etching

#

landscape

#

coloured pencil

#

geometric

#

line

Dimensions: height 203 mm, width 136 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

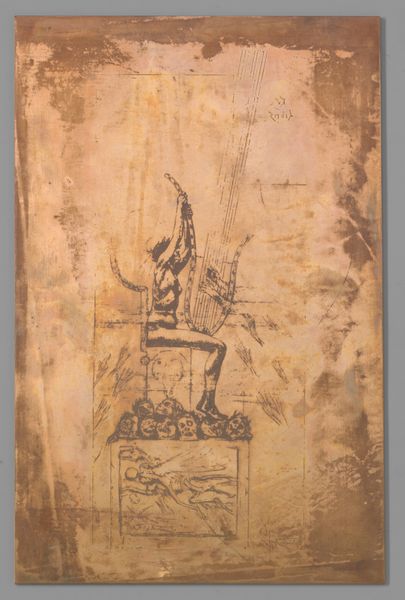

Editor: Here we have "Grafmonument met monogram," a print and etching created by Jean Bernard in 1799, housed at the Rijksmuseum. It has this haunting, almost faded quality. What’s particularly striking to me is the tension between the monument's implied permanence and the ephemerality suggested by the print's fragile state. What's your take on it? Curator: It’s essential to consider the socio-economic conditions that enabled its production. Etchings like this were part of a burgeoning print market. It lowers art’s barrier for a wider audience. Were these accessible materials? Was Jean Bernard responding to a need, feeding the market and the consumption habits of its wealthy patrons, by producing repeatable images of monuments, of legacy? Editor: That's a good point, thinking about it not just as a static object but as a product of its time. Is it fair to see the materials, the etching and print medium itself, as playing an active role in shaping the work's meaning, beyond merely serving as a means of representation? Curator: Absolutely. The line quality in an etching allows for incredibly precise detail, ideal for neoclassical precision. Was that level of intricacy worth it? Moreover, it's interesting to note the inherent reproducibility of prints. Did its material production devalue or democratize the symbolism embedded in that grave marker? Editor: I hadn’t considered how the print medium challenges traditional art values. So the value resides not just in the image, but in its making and its role in a commercial system. Thank you, this has reshaped my appreciation of prints from that period. Curator: Precisely. Thinking through the material conditions unveils new interpretive layers. The consumption, distribution, and social impact become inextricable parts of its art historical relevance.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.