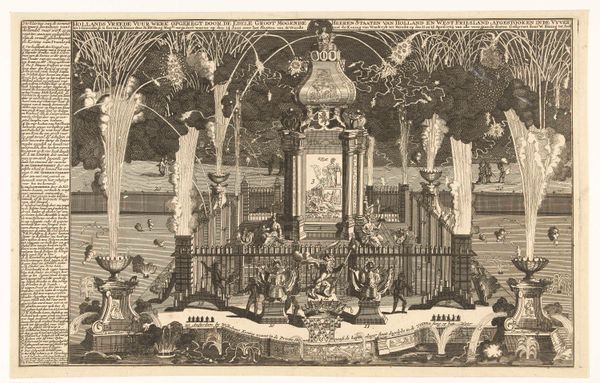

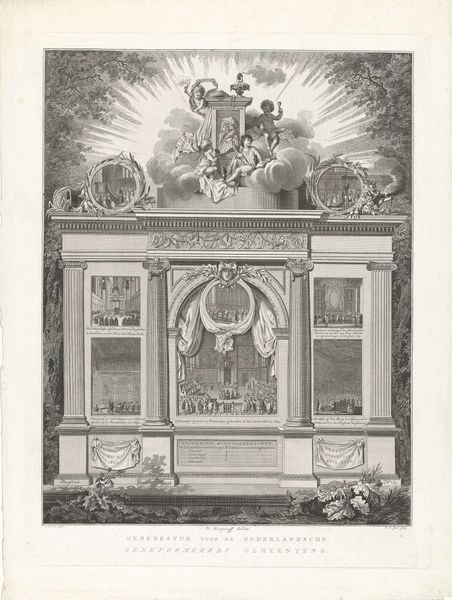

drawing, print, ink, pen

#

drawing

#

narrative-art

#

pen drawing

# print

#

pen sketch

#

figuration

#

ink

#

pen

#

history-painting

#

academic-art

Dimensions: height 678 mm, width 800 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This remarkable drawing is titled "Minerva's troonrede in September 1871" by Johannes Anthony Last, created in 1872 using pen and ink. What are your initial thoughts? Editor: It strikes me as incredibly detailed. The composition, filled with numerous small scenes, almost reads like a political cartoon, yet the style feels very academic, and inherently patriarchal. Curator: Exactly. Let's delve into that tension. Last created this around the tradition of the "troonrede," the Speech from the Throne. Minerva, the Roman goddess of wisdom, is meant to symbolize reasoned, informed governance. Editor: But by visually segmenting the narrative like this, he almost undermines the very notion of unified governance. I see scenes of legal proceedings, public gatherings, suggesting fractured societal power, definitely class differences, maybe highlighting who has access. I wonder about whose voices are prioritized, and frankly, who’s in charge. Curator: Good point. Look at how those smaller scenes function –almost like vignettes commenting on specific aspects of Dutch society in that period. The academic style, of course, lends a certain gravitas, placing the monarchical system within a historical context that suggests order and tradition. Editor: A selective history though, I presume. The absence of certain perspectives can be just as powerful a statement as what is shown. We must ask who this artist served and who paid to create this piece, and whose story are they wanting to convey. Curator: Last worked in a time when print culture became much more central. The rising of illustrated newspapers served to inform society and to give people insight into many social phenomena. We are looking at visuality taking power as a tool of political influence, which still functions similarly today. Editor: And that artistic decision also has its politics. Pen and ink allow for intricate detail, of course, but the monochromatic palette reinforces the impression of historical authority – as if this is some official record presented as evidence. Curator: Perhaps a more subjective, mediated record? It asks, I believe, what images in newspapers are telling the viewer. Who holds that paintbrush, or pen in this case, makes a large difference. Editor: That resonates. Understanding not only the ‘what’ but also the ‘how’ and the ‘why’ of artistic choices truly unpacks what this drawing communicated then, and reveals much about what it conveys to us today. Curator: Agreed. Looking closer challenges simplistic narratives about power and representation.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.