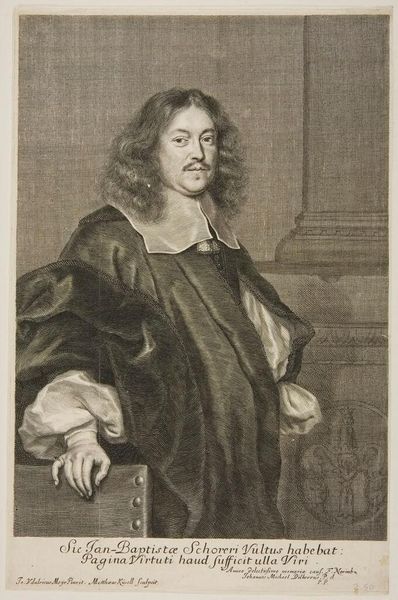

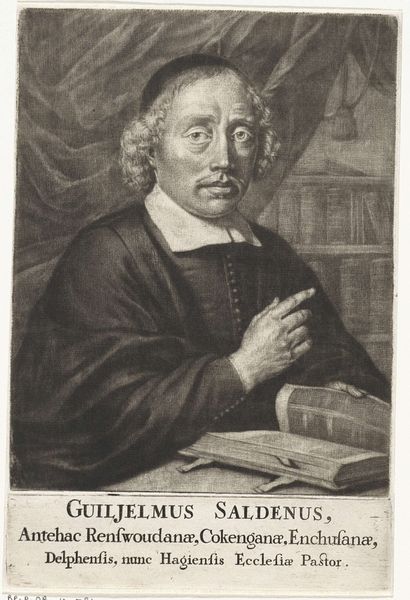

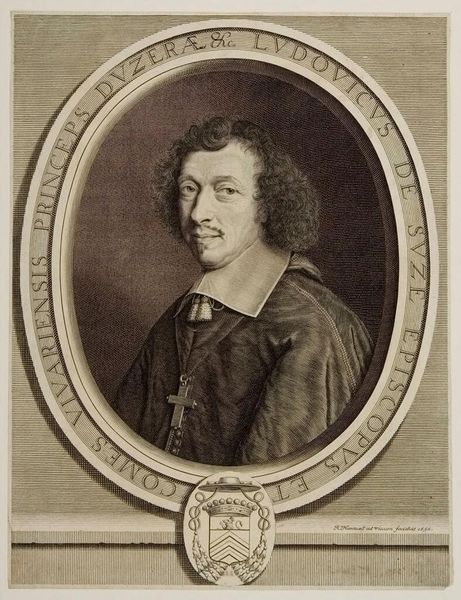

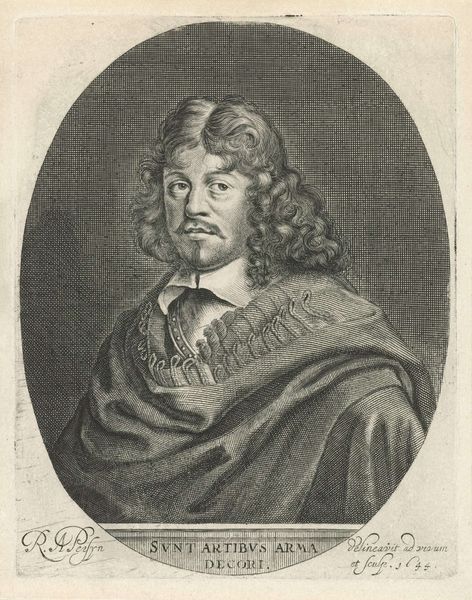

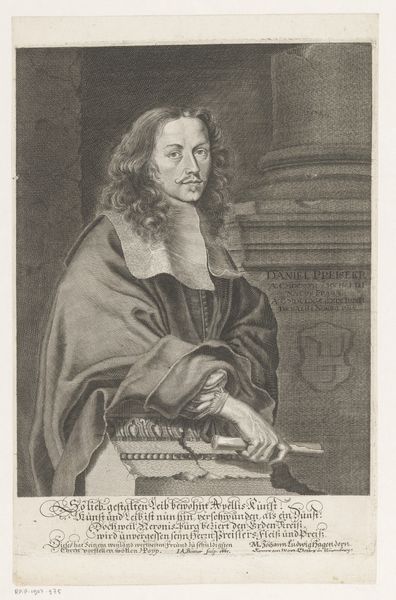

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

self-portrait

#

baroque

#

dutch-golden-age

# print

#

old engraving style

#

figuration

#

line

#

portrait drawing

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 168 mm, width 116 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

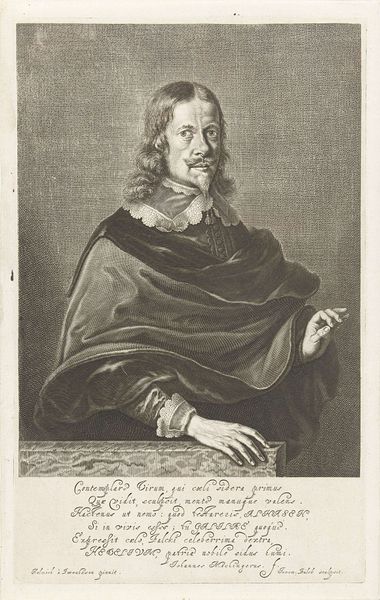

Editor: So, this is Coenraet Waumans' "Portret van de schilder Herman Saftleven" from 1649, an engraving currently held at the Rijksmuseum. What strikes me is how meticulously the lines capture Saftleven's likeness and attire, really showcasing the engraver's skill. What can you tell me about this piece? Curator: Look at the process of this image, at the sheer labor involved in creating such a detailed image through engraving. It highlights a specific moment in printmaking history, revealing the methods by which images were circulated and consumed in 17th-century Netherlands. How do the material realities of this print challenge our understanding of 'fine art' at the time? Editor: That's interesting. I hadn't really considered it as a commercial object. Was engraving seen as a lesser art form compared to painting then? Curator: It's a complicated relationship. Painting often enjoyed higher status because of the direct association with individual artistic genius. However, prints like these democratized art. Think about it – it's an image, widely reproducible. The availability transformed access. It invites the question – who owned paintings and who acquired engravings? Editor: So, while paintings might be unique objects for the wealthy, engravings served a different function, disseminating images and ideas to a wider audience. It blurs the lines between art and commerce, right? Curator: Precisely. Consider how the labor and materials shaped both the image and its social impact. Editor: I see how thinking about the print's materiality really changes how you interpret it. I hadn’t really considered the production process before. Curator: And what have you realized through our chat?

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.