print, photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

print photography

# print

#

landscape

#

social-realism

#

photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

monochrome photography

#

cityscape

#

history-painting

#

monochrome

Dimensions: height 5.5 cm, width 8.5 cm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

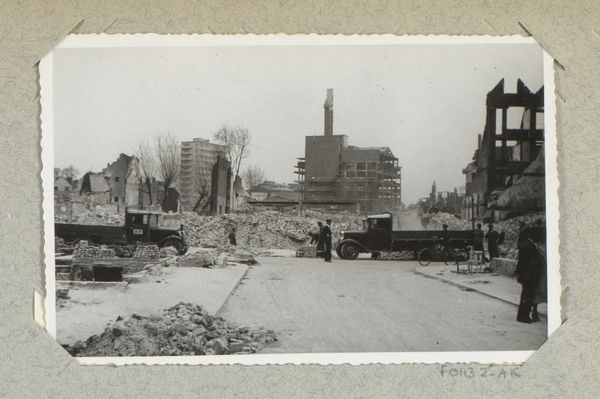

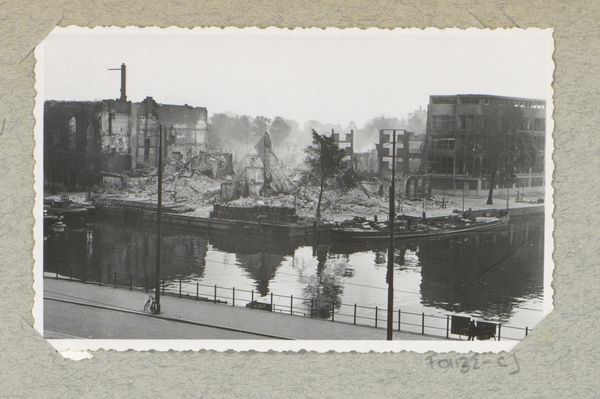

Curator: This gelatin-silver print, titled "Uitgebrande huizen langs het water," or "Burnt Houses by the Water," was created by an anonymous artist sometime between 1940 and 1946. It's currently held here at the Rijksmuseum. What strikes you initially about it? Editor: It's stark, almost post-apocalyptic. The skeletal remains of buildings dominate the scene. The stillness of the water reflects the devastation, creating a mirror image of loss. Curator: The desolation depicted certainly reflects the ravages of war. I think situating this work within the historical context of World War II is essential. We can read this photograph as a potent symbol of the immense human cost and infrastructural damage inflicted during that era. The anonymous nature of the photographer also speaks volumes about the shared trauma of that experience. Editor: Absolutely. The materials themselves also communicate this history of devastation. The gelatin-silver print, a product of specific chemical processes and industrial capabilities of the time, ironically captures the very destruction of the built environment – brick, concrete, and metal – laid bare. I’m drawn to how this photographic method turns the aftermath of something chaotic, the fires and bombs, into this very still, ordered image. Curator: And I see in this a broader intersectional narrative too. The bombed buildings undoubtedly impacted diverse communities disproportionately, based on race, class, and access to resources. Considering urban planning and housing policies of the time, one wonders how those social inequalities contributed to the vulnerability of certain groups represented, or rather unrepresented, within that scene of urban decay. The labor involved in the rebuilding, or lack thereof, too. Editor: Yes, and beyond the grand narratives of war, what labor went into this photograph? Was the photographer a journalist, a soldier, an ordinary person trying to document what they saw? This labor of image-making is often invisible, overshadowed by the more explicit subject matter. Curator: Looking closely, notice that the workers or residents are marginalized in the scene; the damage is centered, not those affected. It becomes a panorama of devastation and points to the state and capital's investment, both material and symbolic. Editor: Ultimately, this work resonates precisely because of the tangible tension between materiality and trauma. We’re confronted with an image produced by specific means at a time of unparalleled material destruction and immense suffering. Curator: Yes. It challenges us to confront uncomfortable histories and ask critical questions about power, representation, and resilience. Editor: A potent reminder of the human cost embedded in every piece of rubble, every grain of photographic silver.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.