drawing, print, engraving

#

drawing

#

ink drawing

#

allegory

#

baroque

#

dutch-golden-age

# print

#

landscape

#

figuration

#

female-nude

#

pencil drawing

#

surrealism

#

genre-painting

#

nude

#

engraving

#

male-nude

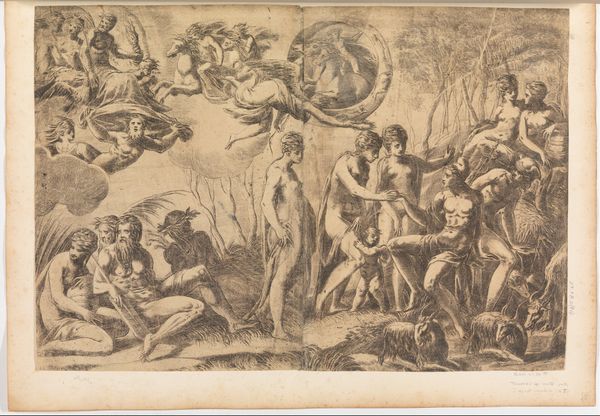

Dimensions: sheet: 12 3/16 x 16 3/4 in. (30.9 x 42.6 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Looking at this piece, it’s like stepping into a dream. Or maybe a half-remembered myth. There’s an abundance of everything – figures, foliage, even…animals chilling. Quite the spectacle, really. Editor: Indeed. This is “The Golden Age,” an engraving created in 1620 by Adriaen Matham. You'll find it in the Metropolitan Museum of Art's collection. What’s particularly compelling here is the artist's capacity to integrate different levels of figuration within a defined space. Note how Matham’s baroque style infuses an allegorical theme with this dynamic visual architecture. Curator: The dynamism is what gets me. You’ve got this central, almost theatrical staging area with people just *living*. It’s like they’re totally tuned in, carefree as anything. No clothes, no problems. Just primal joy, which is both magnetic and also…kinda disconcerting? Editor: That’s a fascinating reading. Think of the orb which provides a backdrop for a lot of the staging of this piece; note that Matham is deliberately drawing attention to it. Curator: True. And the Cornucopia practically bursting from its apex! So you have to ask yourself if Matham thought people living in this age were fully attuned with one another and with nature? Editor: Let us consider that “The Golden Age,” as a concept, traditionally represents an idealized past—an era of peace, prosperity, and innocence. It’s an archetypal longing for a time before corruption and suffering, so there’s always the potential to see what it shows, but also for its value to be placed in things unseen and idealized. This visual construction speaks to utopian ideals and a critique, perhaps implicit, of the present moment, which may have been wracked by social and political upheaval. Curator: You put your finger on it: an imagined counterpoint, a vision of a better time when humans seemed less awful to each other. Looking at all the naturalism and freedom… It gives you hope, while simultaneously hinting at what we’ve lost. A double-edged vision, right? Editor: Precisely. This work remains relevant, and indeed powerful, because it provides more than a historical snapshot. The image becomes a locus where ideals are performed on the picture plane. Its richness lingers precisely because Matham taps into a shared, albeit perpetually unreachable, dream.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.