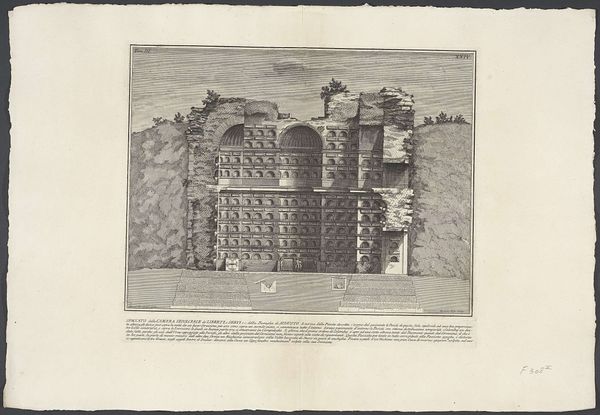

Graftombe van de vrijgelatenen en slaafgemaakten van de familie van Augustus c. 1756 - 1757

0:00

0:00

girolamoiirossi

Rijksmuseum

drawing, print, engraving, architecture

#

drawing

#

aged paper

#

pen drawing

# print

#

pen sketch

#

old engraving style

#

sketch book

#

romanesque

#

personal sketchbook

#

pen-ink sketch

#

pen work

#

sketchbook drawing

#

cityscape

#

sketchbook art

#

engraving

#

architecture

Dimensions: height 377 mm, width 495 mm, height 34 mm, width 495 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

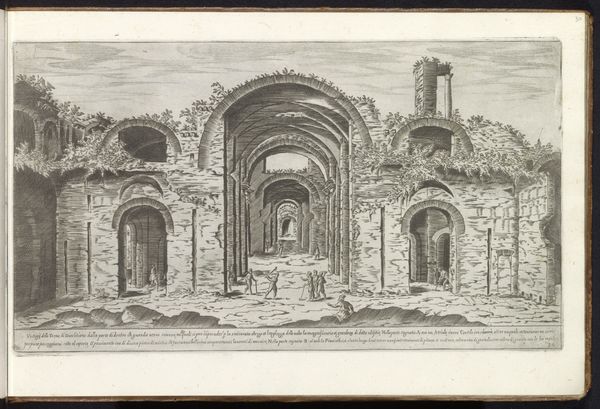

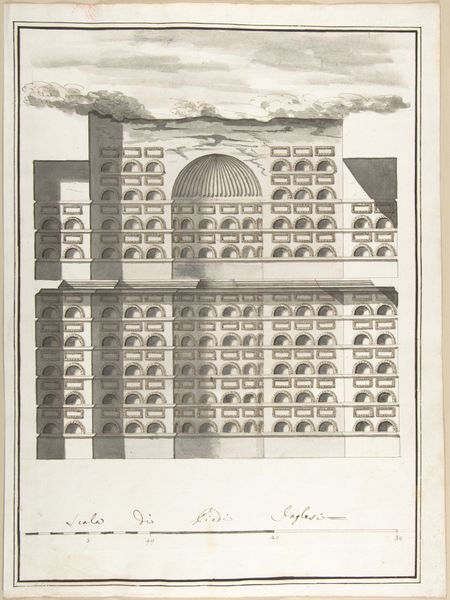

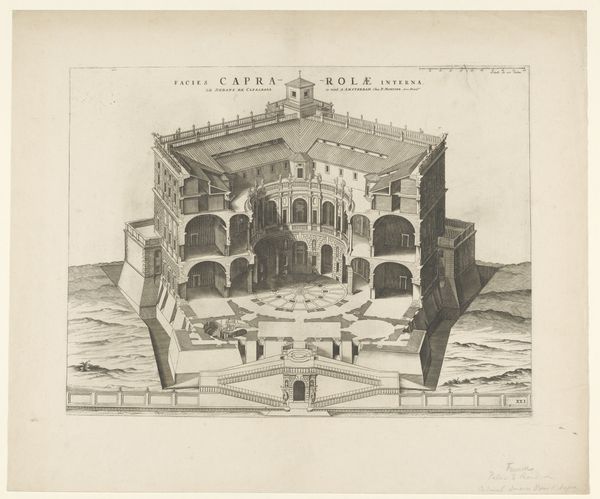

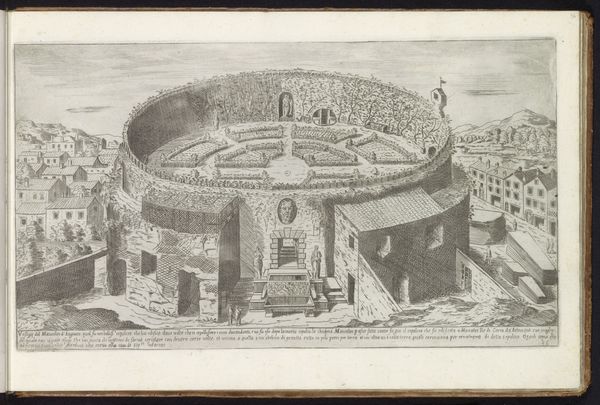

Curator: Looking at this work, my first impression is of rigid organization mixed with ruin. Editor: That’s an apt observation. We’re looking at "Graftombe van de vrijgelatenen en slaafgemaakten van de familie van Augustus," or, "Tomb of the Freedmen and Enslaved People of the Family of Augustus." It's a print by Girolamo (II) Rossi, dating back to about 1756-1757. The Rijksmuseum holds this pen drawing. Curator: The rows upon rows of niches are striking. They lend themselves to a grid-like formalism that is rather compelling. The way Rossi uses line to create a sense of depth, too, is noteworthy. It’s all very balanced, but as I said, the clear decay prevents that balance from becoming static. Editor: Absolutely, and the decay signifies so much in terms of what such structures communicate through time. In ancient Rome, tombs like these weren’t just burial places; they were statements about social standing. By including freedmen and enslaved individuals, this tomb—or this representation of a tomb—offers an interesting, though mediated, glimpse into the complex social hierarchy of the era, and its legacy through this visual depiction from the 18th century. Curator: One could also examine the use of light and shadow here. The way the light catches certain architectural details, creating a sense of three-dimensionality on the two-dimensional surface, invites deeper contemplation. Semiotically, we can decode these light patterns as symbolic of revelation versus concealment. Editor: Good point. And what's particularly poignant is thinking about the labor involved in erecting such a monument. The print hints at stories of those individuals, whose names history may have largely forgotten. What did their contributions to Roman society look like? How might the families who purchased this image have been impacted by these social arrangements? These are all crucial questions. Curator: A worthwhile inquiry into the dynamics between form and the sociopolitical forces it aims to embody. I leave this reflection with the feeling of an art that demands closer visual study alongside its historical study. Editor: Agreed. And perhaps it urges us to consider whose stories get told and how, particularly regarding those historically marginalized.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.