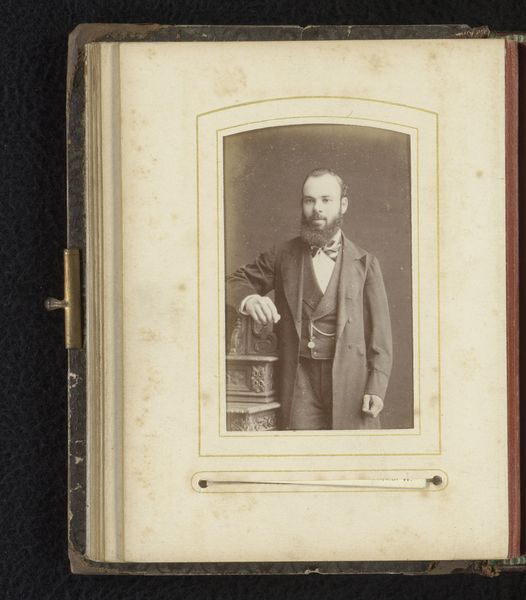

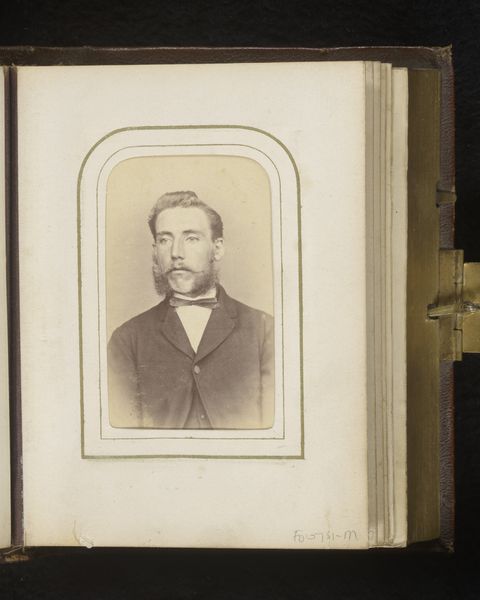

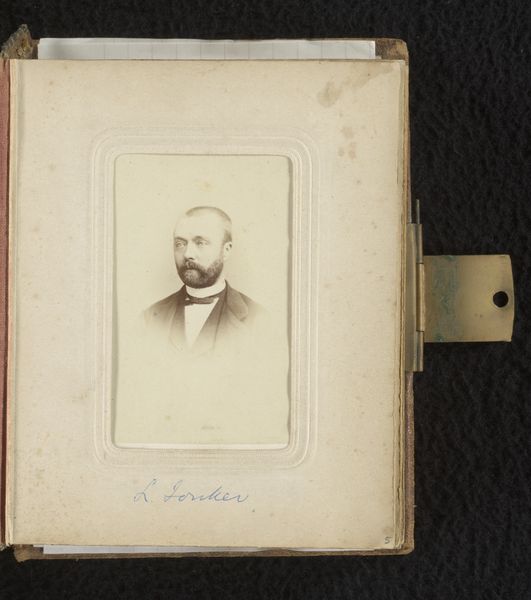

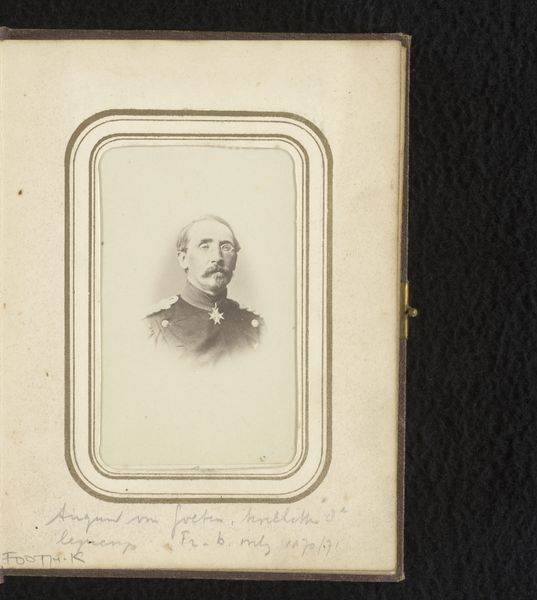

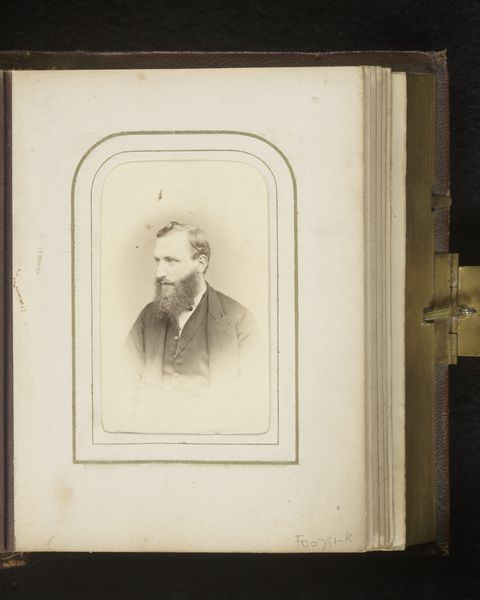

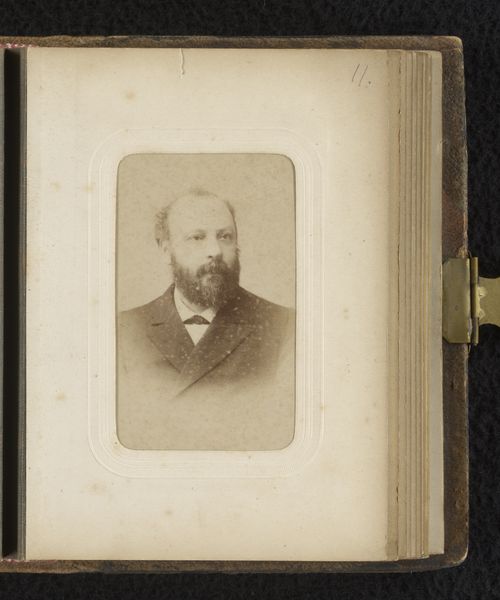

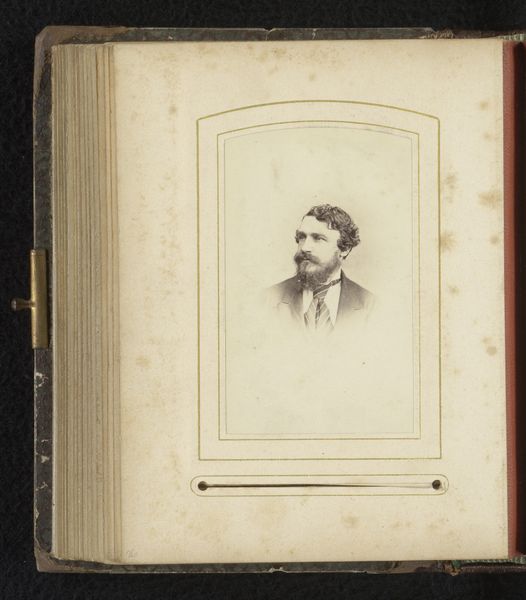

photography, albumen-print

#

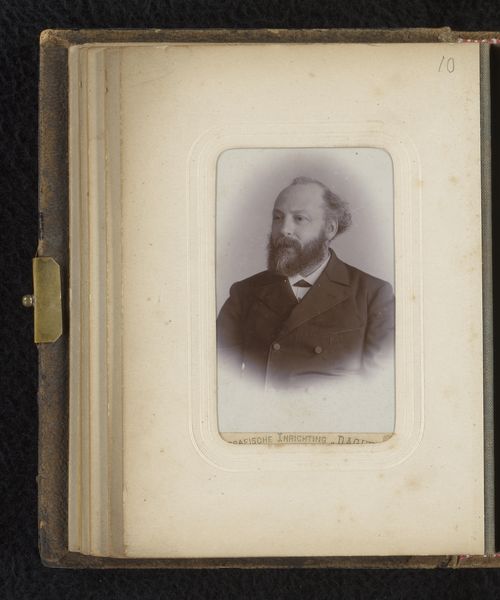

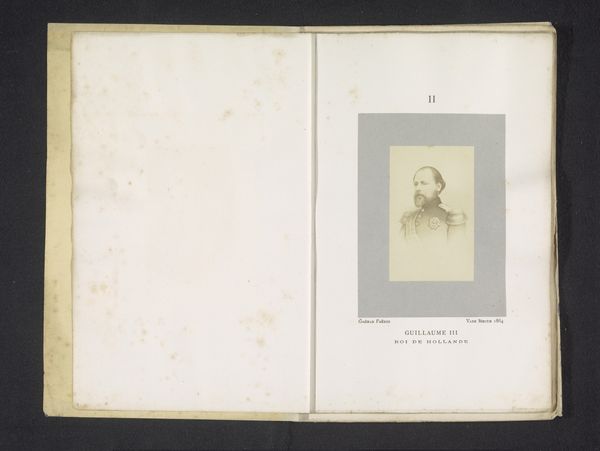

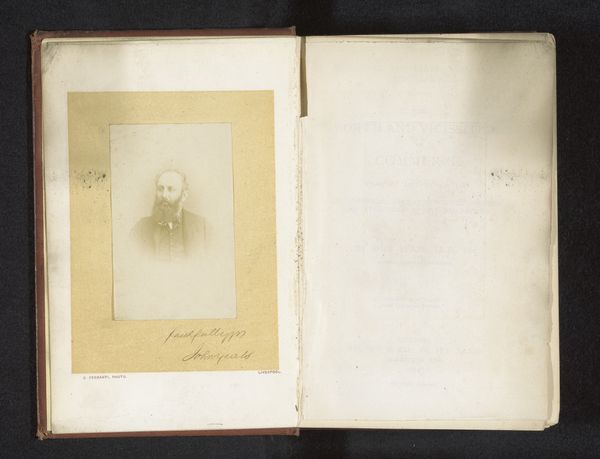

portrait

#

aged paper

#

toned paper

#

antique

#

photography

#

coloured pencil

#

albumen-print

#

realism

#

historical font

Dimensions: height 102 mm, width 62 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: So, this is "Portret van een man met baard," made between 1862 and 1870 by Dixey & Co. It's an albumen print, which gives it that sepia tone. I’m immediately drawn to its antique feel. It makes me wonder about the subject, and his place in society. What story do you think this image tells? Curator: It’s fascinating how studio photography like this contributed to constructing and reinforcing social identities. During the mid-19th century, having your portrait taken became increasingly accessible to the middle class. Consider the performative aspect of portraiture – how does this man want to be seen? His neat beard, his bow tie – it's all carefully considered. How do you think the context of its creation and consumption alters our viewing of this piece today? Editor: That's a great point. He's definitely presenting a cultivated image. Knowing it was for a growing middle class, I wonder about the photographer’s role too. Were they shaping the public image of this new class? Curator: Precisely. Photography studios like Dixey & Co. were not simply capturing images; they were actively participating in shaping the visual language and aspirations of a rising social group. The very act of choosing to have a formal portrait signifies a certain level of economic comfort and social ambition. Notice the deliberate composition. This standardization contributed to establishing social norms and aspirations, defining respectability through visual cues. Editor: That's insightful. It makes me see the image less as a simple portrait and more as a carefully constructed statement about belonging. Thank you, that definitely changes how I interpret the artwork. Curator: Absolutely. These historical portraits aren’t passive reflections of reality, but active participants in social and cultural dialogues, reminding us that the creation and consumption of art are always enmeshed with the politics of identity.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.