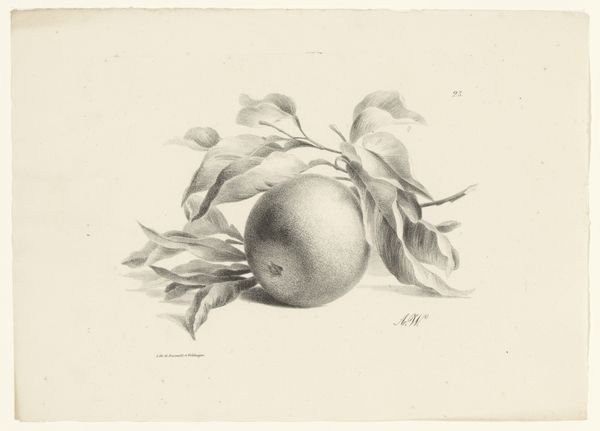

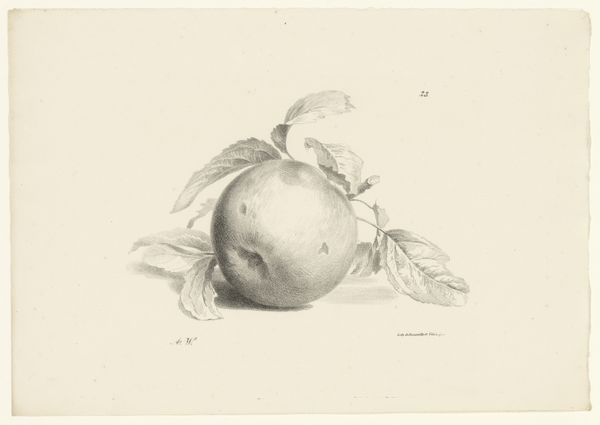

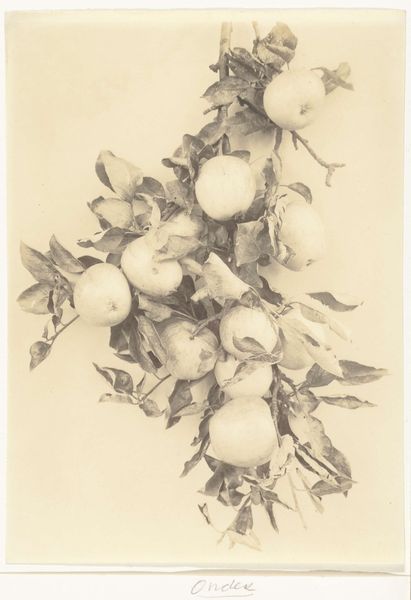

drawing, pencil

#

drawing

#

pencil drawing

#

pencil

#

realism

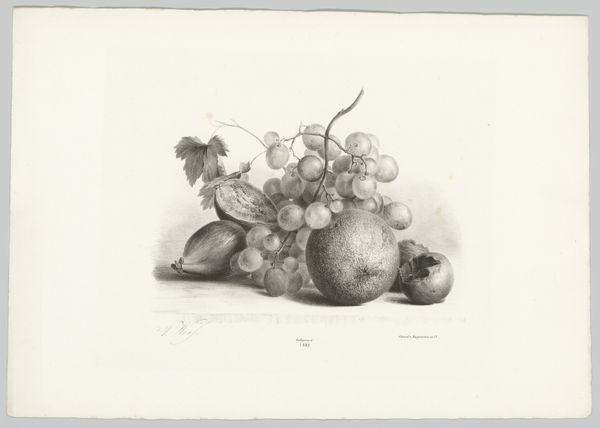

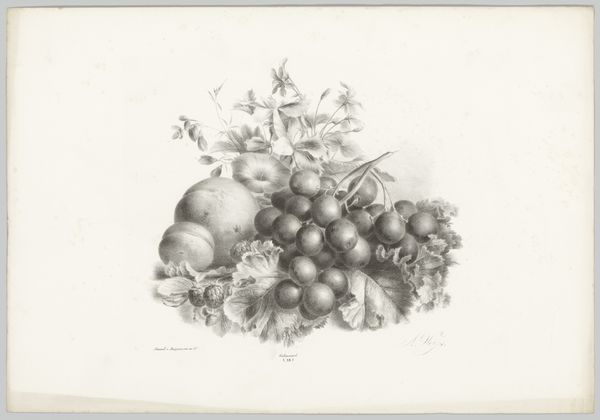

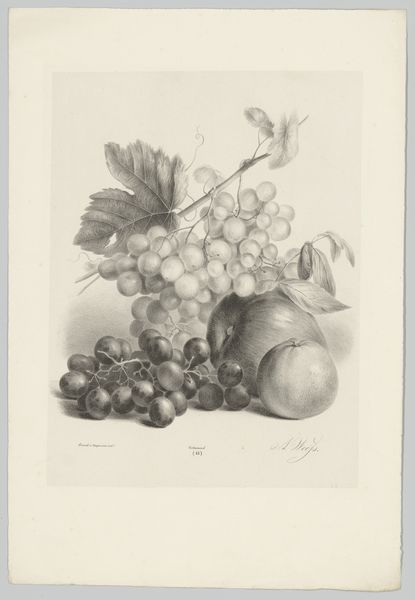

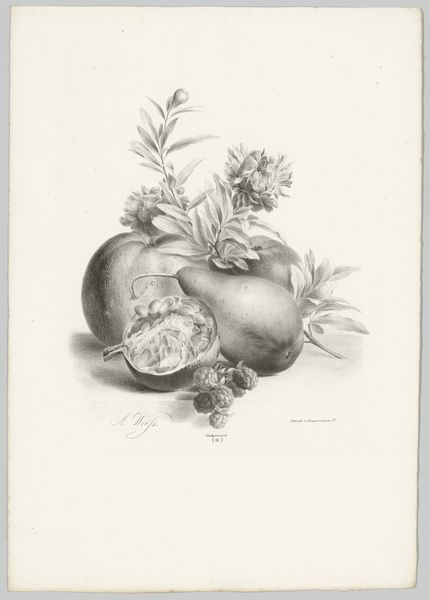

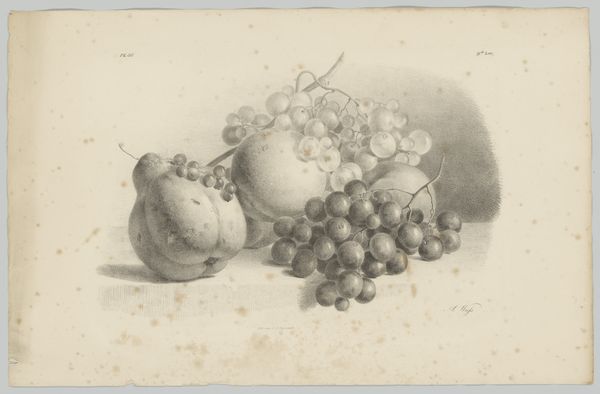

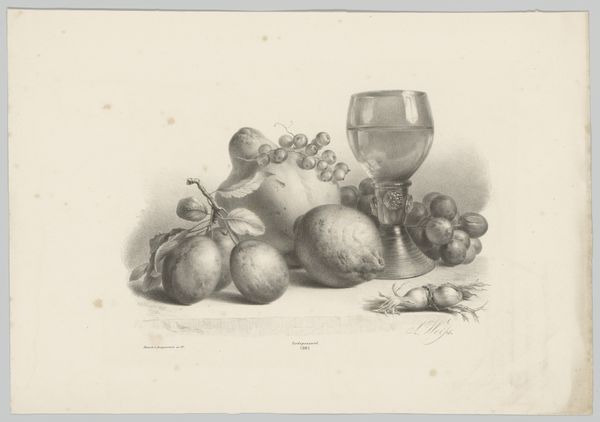

Dimensions: height 295 mm, width 428 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

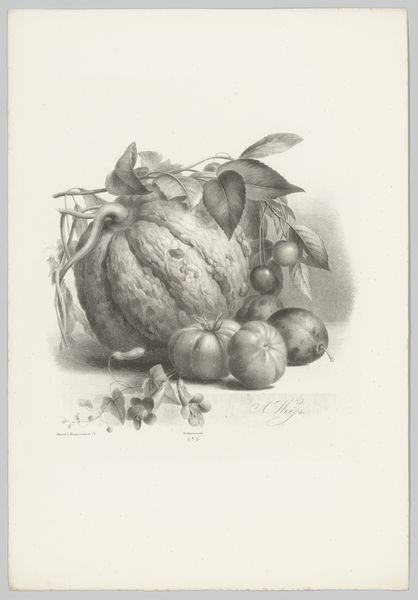

Curator: Welcome. Before us is Anton Weiss's 1836 pencil drawing, "Bloemen, nectarines en hazelnoten," housed here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: The shading gives such depth, it’s nearly photorealistic! And all in pencil. You can practically feel the fuzz on the nectarines and hear the snap of the hazelnuts. Curator: Weiss was working within a well-established tradition. Still life paintings and drawings were incredibly popular in the Netherlands. Works like this served a decorative purpose in homes, reflecting a prosperous, ordered domestic life. Editor: You can tell how much work went into it. The artist clearly had strong drawing skills and intimate understanding of their materials. Pencils like this would have required precise handling, with graphite sourced from specific areas and hand-sharpened. It speaks to a skilled craft and a deliberate consumption. Curator: Absolutely. And the botanical accuracy aligns with scientific interests of the time. It’s a work that suggests cultivated leisure—time to observe nature and refine technique. This precision, while serving an aesthetic purpose, also carried social weight, showcasing refinement. Editor: Interesting, that leisure implies labor. The act of creating these sketches became an opportunity for artists to advance themselves in society. This pencil sketch, so fragile and yet so resilient in its survival, becomes representative of the many lives intersecting within one scene. Curator: And don’t underestimate the quiet power of these images in shaping perceptions. Displaying these works solidified the aesthetic values that were aligned with class and cultural expectations. It reinforced social structures through everyday aesthetics. Editor: The quiet dignity of this still life, a collection of perishable goods rendered so faithfully, transforms them into a moment captured, an embodiment of the social dynamics, material conditions, and lived reality that make up an early 19th-century experience. Curator: I’m left thinking about the ways we both, from different angles, explored not just what’s *in* the artwork, but what it says about how art and society intersect. Editor: And the enduring, accessible quality a simple graphite material carries when considering the value, and how the image presents so much about an era, in terms of skills, craft, consumption, and representation.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.