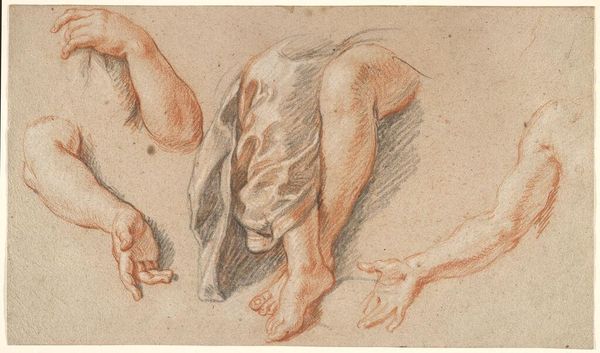

drawing, paper, pencil

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

pencil sketch

#

paper

#

pencil drawing

#

pencil

#

academic-art

#

early-renaissance

#

arm

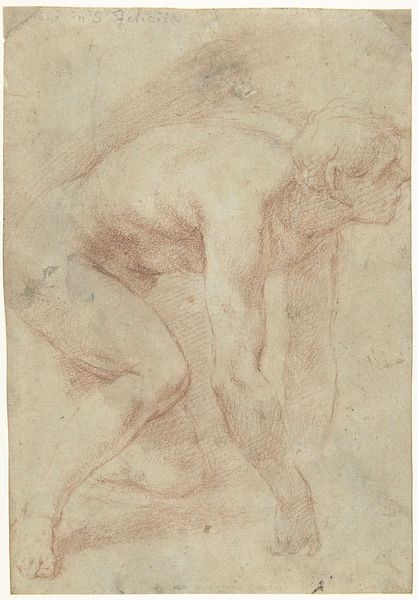

Dimensions: height 257 mm, width 167 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have "Studies of Arms, Hands and Heads" by Abraham Bloemaert, made sometime between 1574 and 1651. It’s a red chalk drawing on paper, currently held at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: It feels like looking over the shoulder of someone learning to draw. A real peek behind the curtain. Curator: Indeed! It’s an academic exercise, rooted in the Early Renaissance tradition. But looking closer, you notice a captivating array of human features capturing various emotional states. I find it really speaks to a kind of internal conflict present in Bloemaert. The individual components suggest deeper stories when considered within the religious tensions and cultural shifts of the time. Editor: Interesting point. To me, the use of red chalk suggests a rawness, an immediacy of material thought. I can almost feel Bloemaert’s hand moving across the paper, trying to grasp the nuances of anatomy and expression. The texture of the paper itself, though now aged, emphasizes the physical act of creation. How would access to quality drawing materials, or lack thereof, shape an artist's production in 17th century Netherlands? Curator: I appreciate you bringing us back to the tangible realities! What about the socio-political element informing this "exercise"? Considering the prevalent use of body studies in religious art of that era, particularly how hands might express devotion or piety, can we view this as an interrogation, or rather a subtle assertion, of humanity’s role within those spiritual narratives? Editor: Possibly. Or is it about democratizing knowledge? These drawings provided templates and techniques that would’ve circulated within Bloemaert’s studio and maybe beyond. Art making in this context feels incredibly collaborative, almost industrial. How would the apprenticeship system further socialize or regiment such art production? Curator: I suppose it all depends on whether you privilege an internal struggle for expressive freedom versus participation in social artistic reproduction, right? Regardless, by considering not just what’s depicted, but the why and how, these fragmentary glimpses start revealing complex ideas about humanity, spirituality, and art making during Bloemaert's era. Editor: Agreed. The drawing reminds me of artistic apprenticeship and the labour and material conditions in the studio during this period. Curator: Exactly.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.