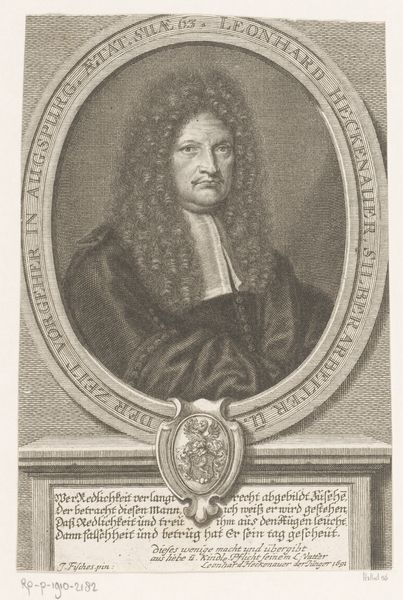

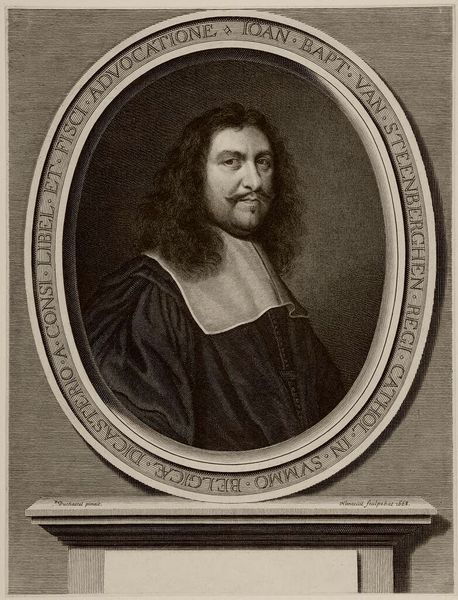

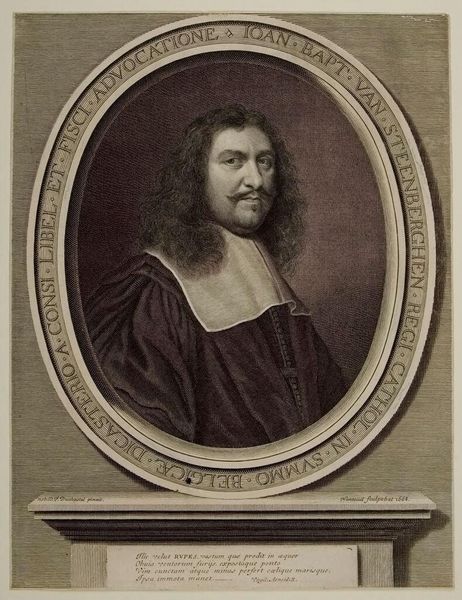

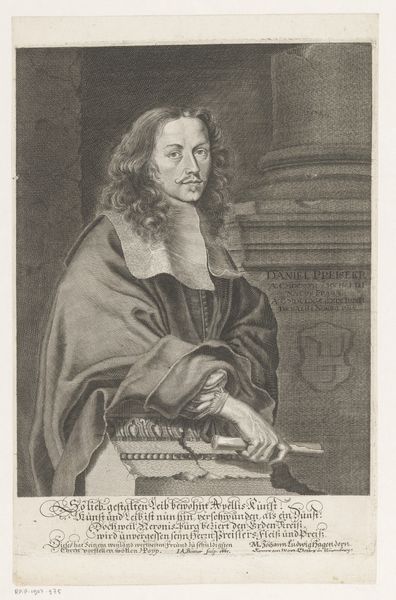

engraving

#

portrait

#

medieval

#

baroque

#

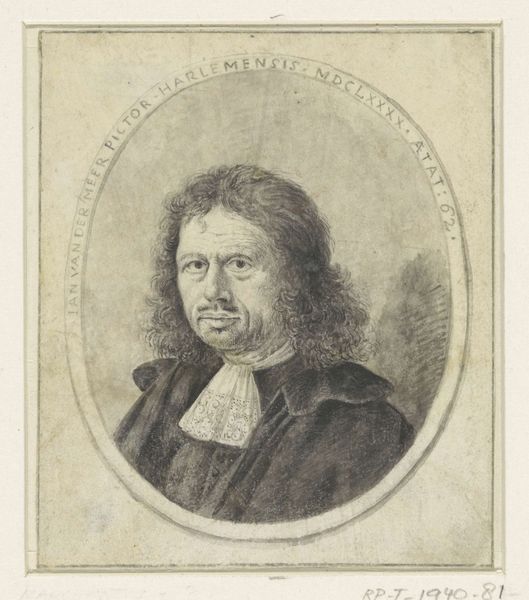

portrait drawing

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 227 mm, width 154 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

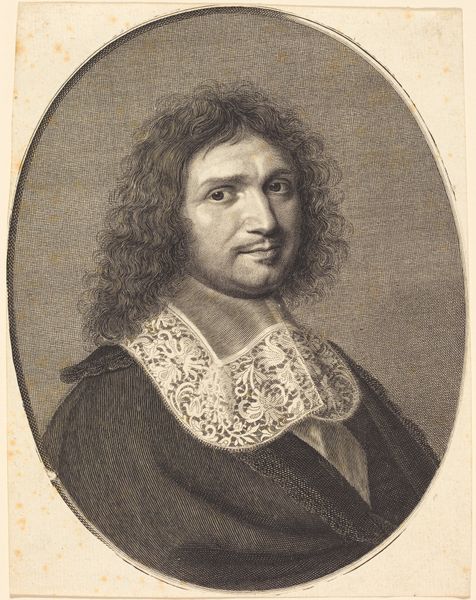

Curator: Lambert Visscher's "Portret van Stanislaus Lubienitzky," made sometime between 1643 and 1691, strikes me as a fascinating example of Baroque portraiture, rendered in engraving. Editor: Yes, it's mostly tonal and somber, made more intimate by its relatively small scale. You can practically see the etched lines that give it that granular depth, like tangible layers of work. Curator: Precisely. Looking at the wider social canvas of the late 17th century, Lubienitzky himself was an astronomer and historian, an important intellectual figure. His inclusion in this formal setting speaks to the value placed on scholarly identity, a trend that saw sitters drawn from an emerging professional class eager to inscribe themselves within established social hierarchies. Editor: I'm particularly struck by how Visscher’s method reinforces this social elevation. The engraving, with its reproducible nature, facilitated the widespread dissemination of Lubienitzky's image. In an era when the cost and skills were high, producing copies, in essence, democratizes his representation even though, of course, his portrait wouldn't reach ordinary citizens. The labor embedded in the creation of those etched plates allowed this person to be memorialized. Curator: True. There’s that intriguing interplay between individual identity and the sociopolitical systems at play. Lubienitzky’s gaze—somewhat introspective—combined with the inscription below suggests an almost idealized notion of scholarly zeal and religious virtue, values upheld by both the Protestant and early Enlightenment elite. Editor: And think about the circulation of prints as a social exchange, connecting artists, patrons, and the wider public in a visual conversation about status, knowledge, and even the dissemination of propaganda. Each print that emerges bears testimony to a nexus of exchanges tied to this person's political, and religious standing. Curator: Right, these weren't merely artistic creations. They functioned as objects that codified and reaffirmed certain modes of being, contributing to the establishment of enduring societal narratives. Editor: Exactly. By focusing on the processes of artistic production and circulation, we glimpse how power dynamics were constructed and how visual communication played a critical role in the maintenance of a given social and political order. Curator: In delving into the life and representation of Stanislaus Lubienitzky through this lens, we surface the cultural underpinnings of societal status and intellectual prowess that remain remarkably resonant today. Editor: The material conditions behind image-making offers concrete insight into that world. It encourages questioning who controls these image-making means, which continues to echo loudly today.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.