print, etching

# print

#

etching

#

war

#

landscape

#

history-painting

#

modernism

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

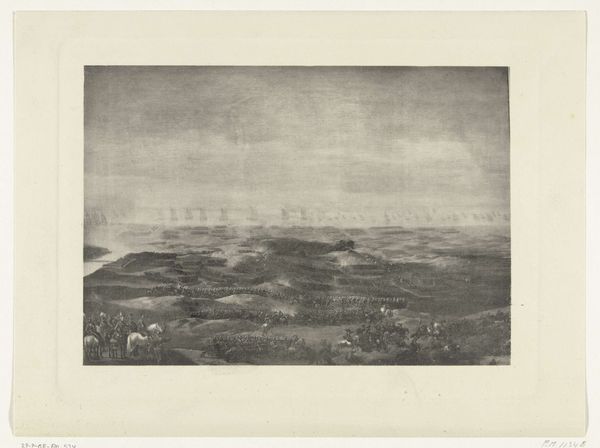

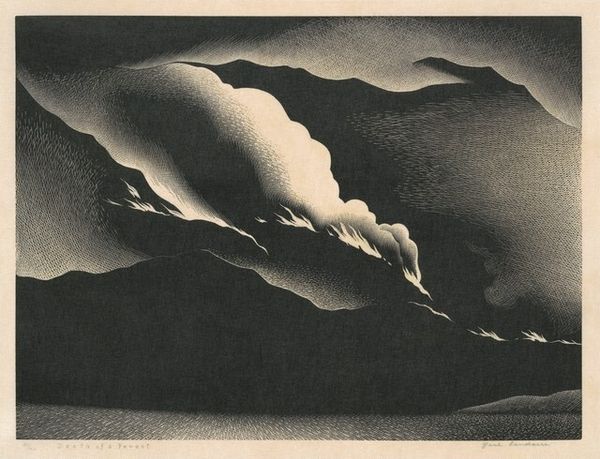

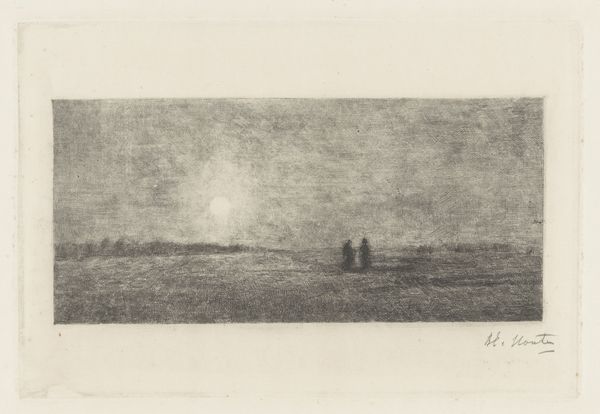

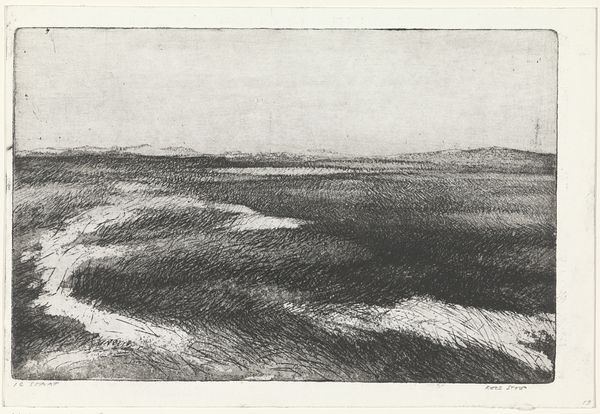

Editor: This etching, "September 13, 1918, St. Mihiel" by Kerr Eby, dated 1934, uses a monochrome palette to create a solemn scene. What strikes me most is the looming darkness in the sky, a sense of overwhelming dread. What do you see in this piece? Curator: I see a landscape heavy with symbolic weight. The desolate field, punctuated by those stark, broken trees, functions almost as a memento mori, reminding us of mortality and loss. The darkness you observed isn’t just literal; it speaks to a collective trauma. It acts almost as a visual representation of the psychological weight carried by survivors and by extension, our cultural memory of the war. Do you notice how the lines of soldiers seem to dissolve into the landscape itself? Editor: Yes, they almost look like rows of decaying crops, blending with the churned earth. What’s the significance of that, do you think? Curator: It blurs the boundary between man and nature, emphasizing war's destructive power over both. The soldiers, arranged almost anonymously, become a part of the devastated land. Eby is creating a space charged with cultural meaning, where the individual fades into a representation of universal suffering. This visual merging has been used throughout history as a symbolic image in cultural memory and grief. Consider other artists depictions, what symbols and representations overlap? Editor: So, it’s not just a historical depiction, but a kind of symbolic landscape of grief and memory? That's insightful; I hadn't considered the way the artist connects the figures to the devastation of the land itself. Curator: Exactly. And think about how Eby chose to create an etching rather than, say, a painting. The medium itself, with its delicate lines and somber tones, lends itself to conveying a sense of fragility and impermanence. Editor: I see what you mean. The printmaking process adds to that feeling of a moment captured and preserved, but also vulnerable to fading with time. I now see so many layers that I didn’t recognize at first glance. Curator: Indeed, its power resides in its capacity to function as both a historical document and a deeply resonant symbol of loss and remembrance.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.