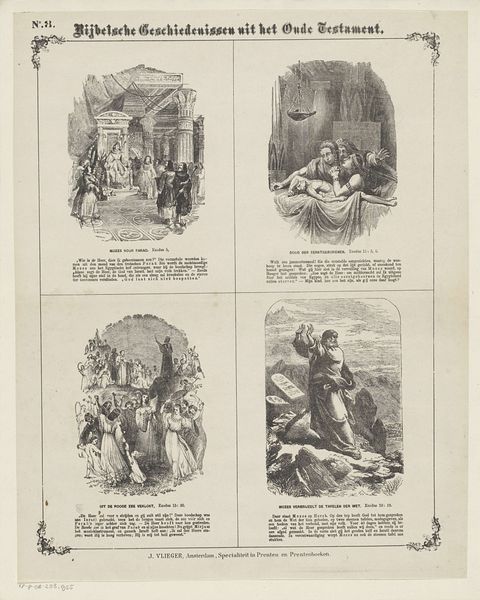

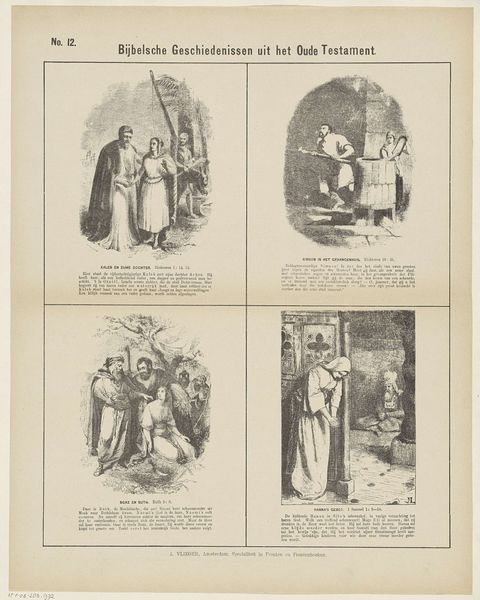

print, engraving

#

aged paper

#

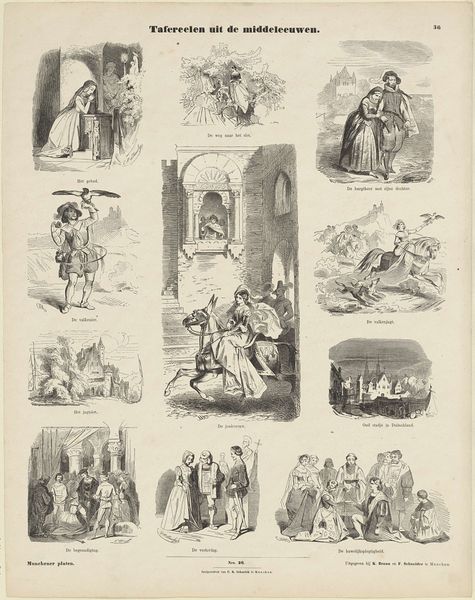

medieval

#

page thumbnail

#

narrative-art

# print

#

old engraving style

#

traditional media

#

old-timey

#

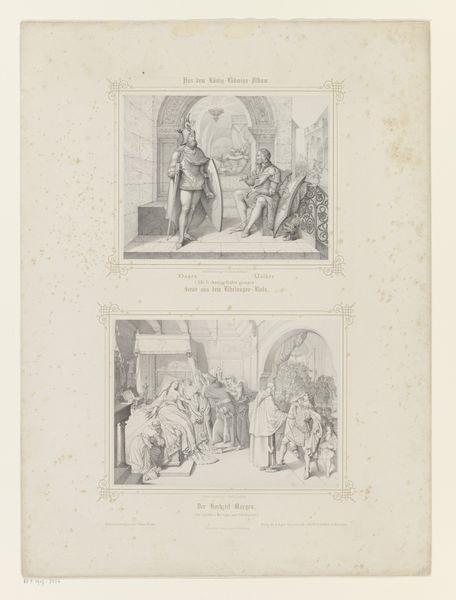

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 422 mm, width 328 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

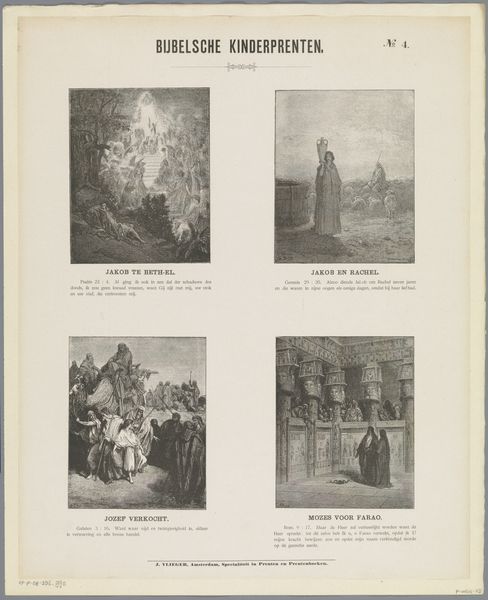

Curator: This print, dating from between 1866 and 1871, is titled "Biblical Stories from the Old Testament" and appears to be the work of S. Sly. The medium is engraving, presenting various narrative scenes. My initial reaction is one of contained chaos. So much narrative compressed into distinct vignettes, battling for attention on a single sheet. It is reminiscent of medieval illuminated manuscripts. Editor: It absolutely evokes that sense of didactic medieval imagery. Each of those small scenes is dense with its own iconography, practically vibrating with significance. We have vignettes of Elijah, one depicts mourning near classical columns, and scenes featuring men in distinctive robes. The symbols, gestures, the visual shorthand would all speak volumes to its contemporary audience. Curator: Absolutely, and these would have been understood within very specific socio-cultural frameworks. Consider its original setting – probably in the home – its role might have been both devotional and educational, shaping beliefs within the domestic sphere. The layout of the print mimics earlier examples of cheap print, and speaks of this object's circulation within a broader public than simply a wealthy elite. Editor: Looking closely, the way the artist renders the garments— the specific hats worn, the folds in the fabrics— speaks to deeply entrenched cultural markers. These weren't simply illustrations; they visually reinforced specific societal roles and values, almost acting as blueprints for how people should conduct themselves. The architecture even reinforces this hierarchical understanding of space. Curator: And of course, there’s the political implication too; what stories were selected, and how were they represented to legitimize the contemporary religious and social institutions. That would shape not only beliefs but the political structures around them. Editor: Yes, it's less about innocent illustration, more about creating a visual language of power, tradition, and belief. The power in symbols persists. Curator: This piece makes one consider just how carefully controlled images could shape worldviews in the nineteenth century and invites one to investigate the public function of such art, its ability to teach. Editor: Indeed, by dissecting the dense symbolism, we glimpse the emotional and ideological landscape of the past, and how such symbols echo into the present.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.