print, etching

#

ink drawing

#

narrative-art

#

baroque

#

pen drawing

# print

#

pen sketch

#

etching

#

landscape

#

figuration

#

line

#

cityscape

#

genre-painting

#

history-painting

#

realism

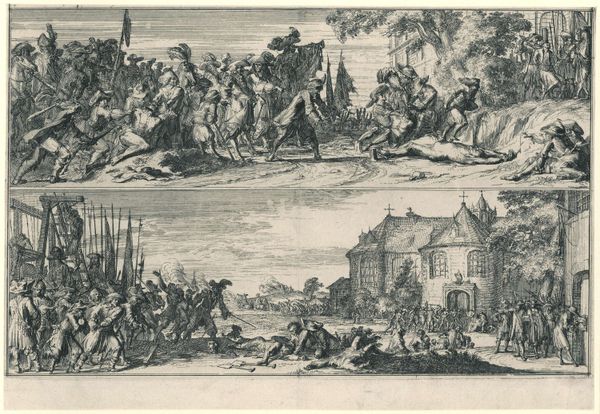

Dimensions: height 203 mm, width 303 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

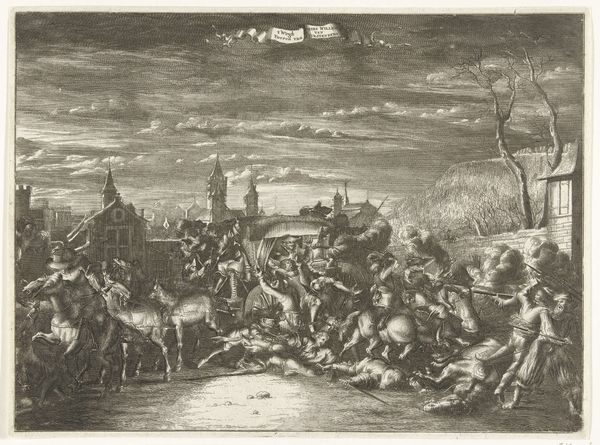

Curator: This etching by Romeyn de Hooghe, created in 1673, is titled "Atrocities in a Village during Winter, 1672". It’s currently held in the collection of the Rijksmuseum. What’s your initial impression? Editor: The eye is drawn immediately to the swirling chaos. The density of the lines creates a frenetic energy. The light and dark contrasts certainly emphasize the carnage and evoke a feeling of deep unrest. Curator: Indeed. De Hooghe made this work in the aftermath of the Franco-Dutch War. It depicts the widespread violence perpetrated by invading French troops in the Dutch Republic, especially in the "disaster year" of 1672. This image would have circulated widely as a form of political propaganda, demonizing Louis XIV's armies. Editor: That context shifts everything. Suddenly, those dynamic lines feel less purely expressive and more deliberately propagandistic. But even acknowledging its historical purpose, one cannot overlook how effectively he uses linear perspective. Notice how the lines converge, forcing the viewer's focus into the burning village in the distance, emphasizing the totality of the destruction. Curator: The composition aims for a shocking immediacy. By filling nearly every bit of space with detail, de Hooghe overwhelms the viewer. Look how figures in the foreground draw the viewer in, implicating the Dutch population directly. Consider the public that viewed this. How powerful this narrative would be for a population enduring political and economic turmoil. Editor: It's intriguing how de Hooghe uses line not just for representation but also for emotional expression. The scratching, hurried strokes contribute to the overall sense of panic. It does leave one wondering: how much of the depicted cruelty did de Hooghe witness, or was it simply constructed through available anecdotes, contributing to historical representation as art? Curator: Exactly. And we should consider how printmaking served political objectives, shaping public sentiment toward international affairs. These prints, displayed and disseminated across social strata, became powerful visual tools, integral to forming shared sentiments about governance and societal direction. Editor: Yes, de Hooghe’s lines certainly served something larger, reflecting society's narrative, making this seemingly brutal artwork ultimately meaningful.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.