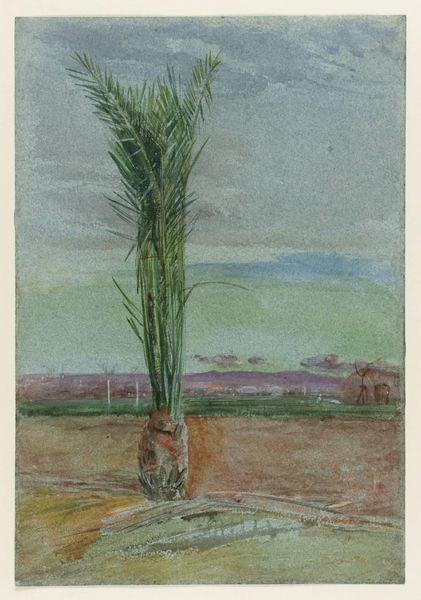

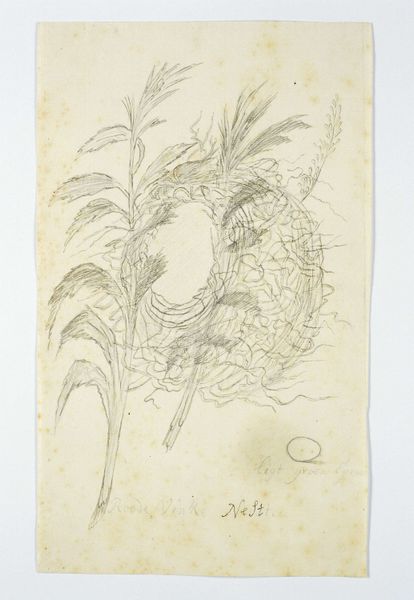

![Tropical Plant [recto] by Jane M. Stanley](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fd2w8kbdekdi1gv.cloudfront.net%2FeyJidWNrZXQiOiAiYXJ0ZXJhLWltYWdlcy1idWNrZXQiLCAia2V5IjogImFydHdvcmtzLzMzM2ZkNjZhLWUwZDktNDIyZS1hNDRhLTFmOWJkYmFiMGNmOC8zMzNmZDY2YS1lMGQ5LTQyMmUtYTQ0YS0xZjliZGJhYjBjZjhfZnVsbC5qcGciLCAiZWRpdHMiOiB7InJlc2l6ZSI6IHsid2lkdGgiOiAxOTIwLCAiaGVpZ2h0IjogMTkyMCwgImZpdCI6ICJpbnNpZGUifX19&w=1080&q=75)

Dimensions: sheet: 45.72 × 35.56 cm (18 × 14 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

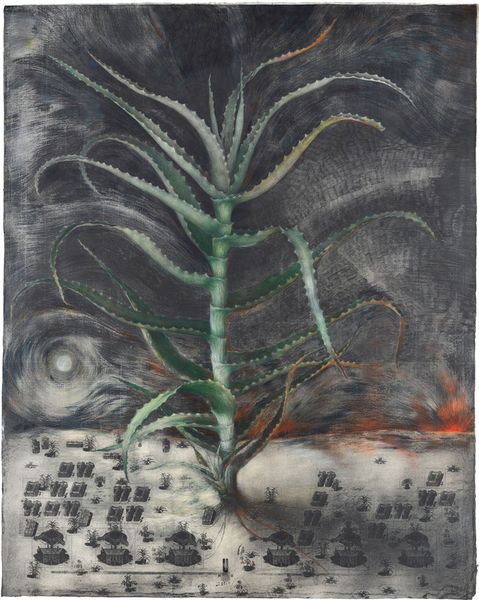

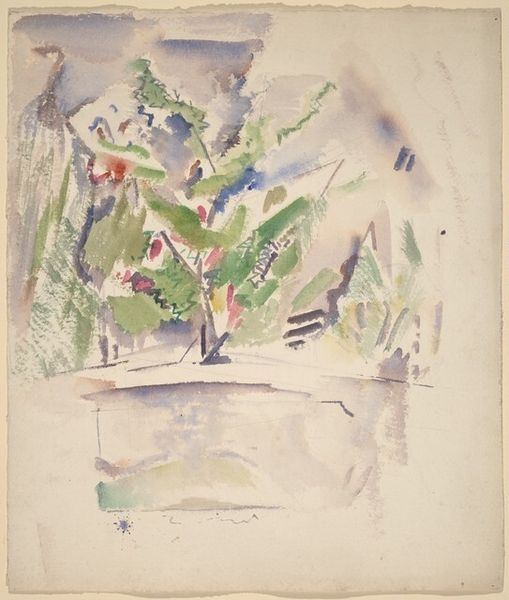

Curator: Here we have Jane M. Stanley's "Tropical Plant," likely created around 1930. The primary media appear to be watercolor and colored pencil on paper. Editor: It strikes me as serene. The limited palette—mostly muted greens and earth tones—creates a rather contemplative mood. There's an intimacy despite the potentially imposing subject matter, likely caused by the composition’s flattening effect. Curator: Absolutely. If you look at the composition, there’s an emphasis on surface, isn't there? The blurring of background and foreground minimizes depth, which underscores the texture. The application of watercolor displays a distinct structural logic in the overlapping fronds. The individual marks become quite visible. Editor: Right, I wonder about Stanley's intentions at this time, since this aesthetic feels somewhat anomalous considering interwar sociopolitical pressures. It could also represent colonial interests in "exotic" botany, subtly reflecting class or even geopolitical hierarchies of the period. After all, "tropical" itself is often loaded. Curator: An interesting point, but observe how the almost symmetrical balance redirects attention away from any inherent cultural reading of 'tropicality.’ The thrust of the painting lies in these repetitive lines—frond, then shadow, frond, then shadow. Stanley makes sure we notice the basic geometries and color values. The shadows themselves are fascinating, acting like near replicas of the main botanical form. Editor: Yet can we fully disconnect those geometries from Stanley’s identity? Perhaps her perspective as a woman informs how she engages with and interprets such botanicals—considering, for example, how gender shapes labor connected to agriculture or travel to exotic landscapes for plant studies at that time. We must ask: from whose vantage point do these structures exist? Curator: Those are essential questions. But equally relevant here is that by studying form—and color shifts as form—we develop ways of seeing apart from strict representation, or social intention. To reduce art down to symbolic shorthand denies, in this instance, Stanley’s manipulation of materiality. Editor: A tension, I suppose, between seeing and situating. Nonetheless, engaging art in context deepens—it never reduces. Thank you for guiding me, as ever, to engage with it more acutely. Curator: And thank you for ensuring we consider these things beyond purely formal qualities.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.