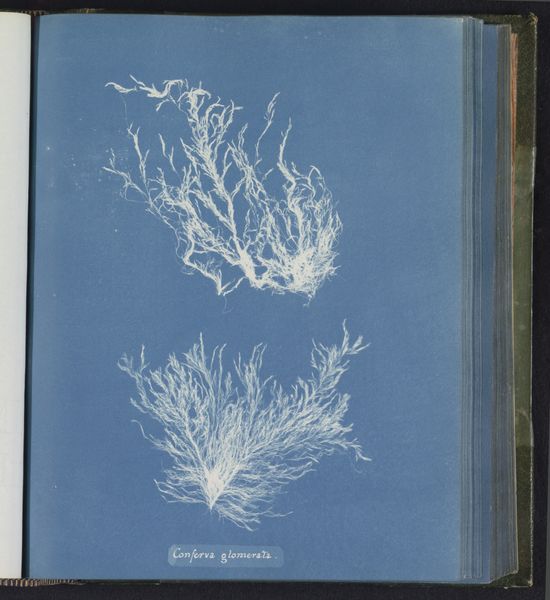

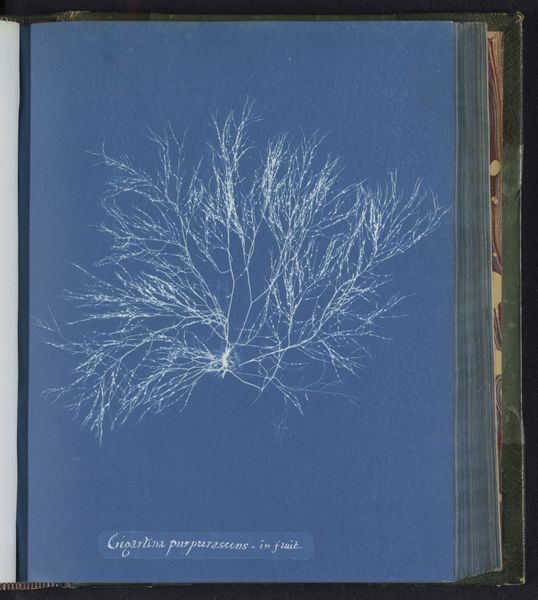

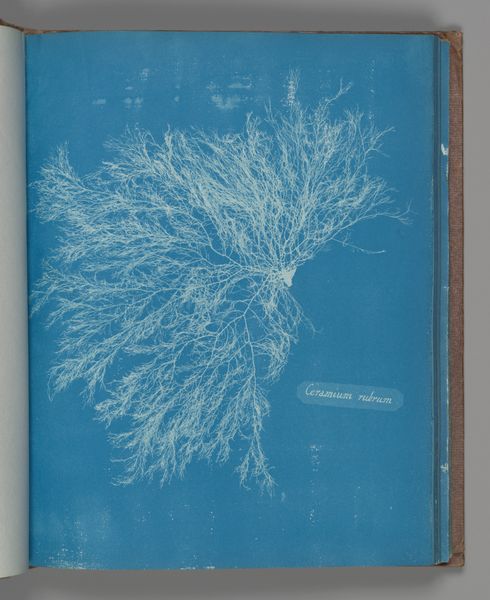

print, cyanotype, photography

#

still-life-photography

# print

#

form

#

cyanotype

#

photography

#

coloured pencil

#

line

#

realism

Dimensions: height 250 mm, width 200 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

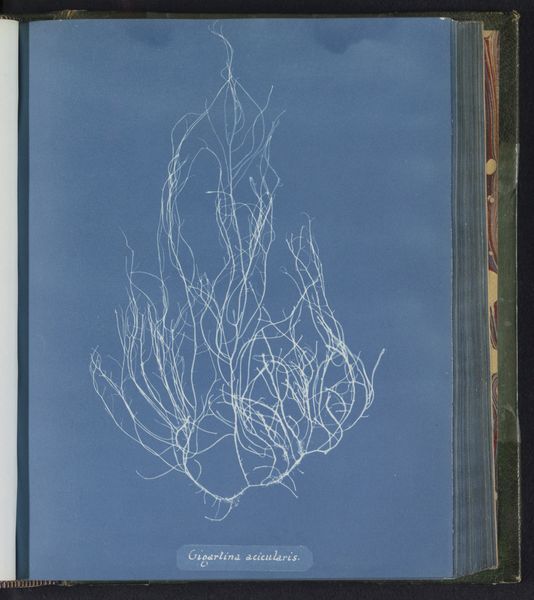

Curator: Before us, we have Anna Atkins’ "Gigartina confervoides," a cyanotype likely created between 1843 and 1853. It is a stunning example of early photographic processes. Editor: The stark contrast immediately grabs me – the delicate, almost ethereal, white algae against that intense Prussian blue. There’s an undeniable simplicity to it, yet it possesses this incredible depth, inviting you in to explore the details. Curator: Indeed. Atkins' choice of cyanotype printing transforms seaweed, gathered through Victorian beachcombing, into photograms. What seems like simple reproduction highlights the era's merging of scientific cataloging and artistic experimentation, questioning how we classify knowledge. Editor: But it is also the way she captures light. See how the form is emphasized using that one tone? What is usually submerged and unseen takes on a graphic quality and creates these elegant, flowing lines against the flat, uniform ground of cyan blue, all based on photographic accidents as much as design. It becomes something so structurally interesting... Curator: A consequence, precisely, of this era of experimentation. Remember that Anna Atkins made these photograms not for purely aesthetic purposes, but to illustrate her books on British algae, so it was an exploration of image reproduction that blurred lines between science, industrial labor and aesthetics, which questions what constitutes the fine arts, especially within the framework of photographic reproducibility. Editor: Right, I agree, but its enduring power is because it is aesthetically so engaging; the arrangement of the seaweed takes on a kind of organic pattern, or a stylized diagram, prompting viewers to consider botanical structure. A fusion between form and function. Curator: Definitely, seeing these works as evidence of cross-pollination between scientific discovery and artistry allows us to interrogate traditional views of craft in the artistic context. Editor: Ultimately, what I find myself admiring most is its capacity to still resonate today; that combination of striking imagery and thoughtful, intellectual curiosity renders the piece powerful, almost 200 years on.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.