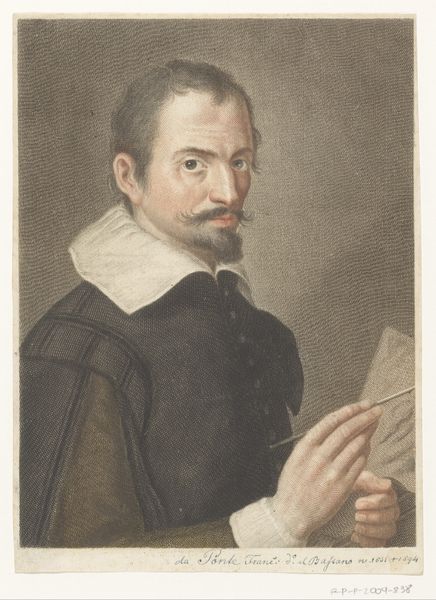

drawing, coloured-pencil

#

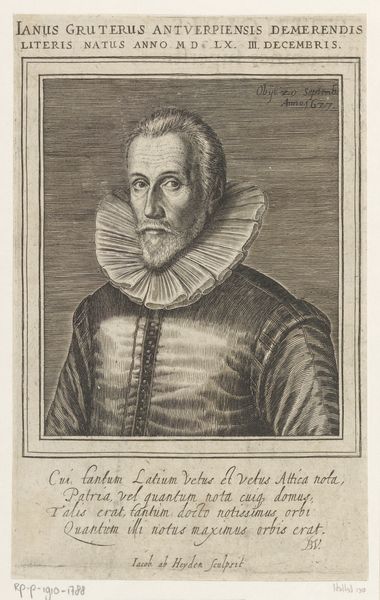

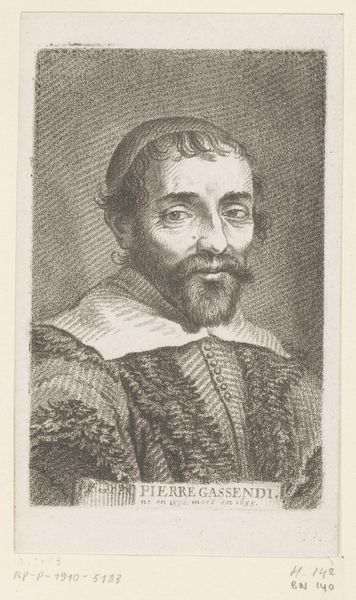

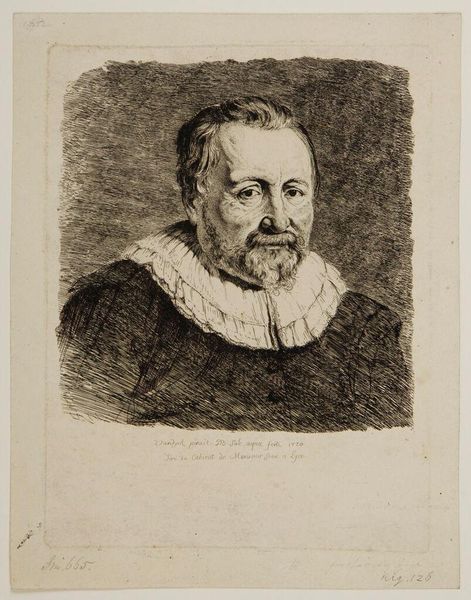

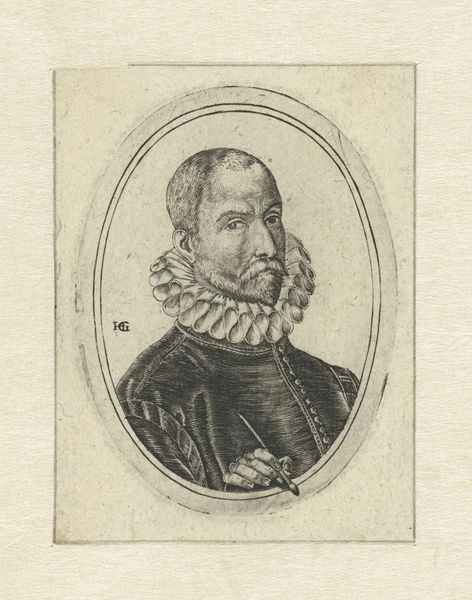

portrait

#

drawing

#

neoclacissism

#

coloured-pencil

#

charcoal drawing

Dimensions: height 170 mm, width 130 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: There’s something rather charming about this portrait, isn't there? It's almost ethereal, created using colored pencils in 1789 by Carlo Lasinio, and it depicts Rutilio di Lorenzo Manetti. Editor: Charming is one word. I immediately focus on the ruffle – the precise labor involved in creating such a perfect circlet of fabric is quite compelling. And the almost raw quality of the mark-making, juxtaposed with the ostentation of his attire—it points to the hierarchies of artistic production at play. Curator: Indeed. Neoclassicism often engaged with notions of class, power, and the spectacle of governance. It makes me think about who commissioned these works. Editor: It’s crucial to ask how such imagery was circulated. Prints, drawings...they’re commodities as much as representations. Was this designed for mass consumption, or was it more exclusive, further elevating the sitter’s status through the sheer expense and craft of the image itself? And was he really worth such trouble? Curator: Manetti was a painter himself; understanding the art world ecosystem helps to ground the picture in its cultural setting. He had his own prominent workshop... Lasinio immortalizing Manetti serves both as a transaction and validation of their craft. Editor: It is about craft, and the tools used. Looking closely, one appreciates the textures. The tooth of the paper, the layering of pigments to create subtle modulations of tone in his face and that dazzling ruff...these are signs of skill deployed towards very particular social ends. What was the intent in using color? Curator: At the time, color elevated a work from mere draftsmanship toward the illusion of painting; it was aspirational and brought associations with history painting, or other prestigious genres. But more than just surface level associations, the shades and shadows in Manetti's expression may reveal something about how people viewed their place in that world, given that the portrait arose during the tumultuous end of an old order. Editor: Yes, all those things come together when looking back at it. Examining these traces allows us to see a network of producers, consumers, and meaning-makers tied up with social aspirations, more than mere pretty artwork, even if in such miniature form. It gets us somewhere useful, I think. Curator: I concur, tracing these social roots gives added richness to the act of gazing.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.