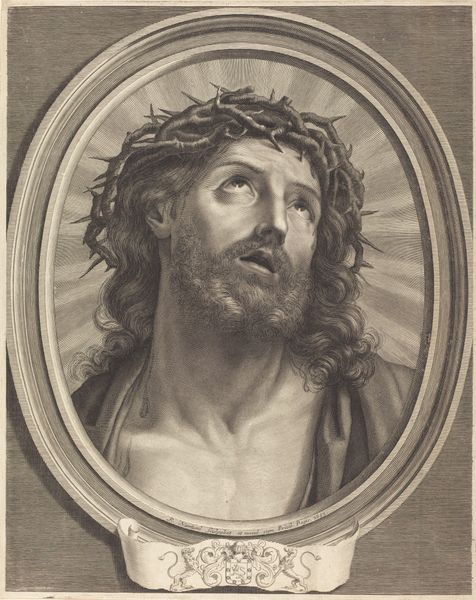

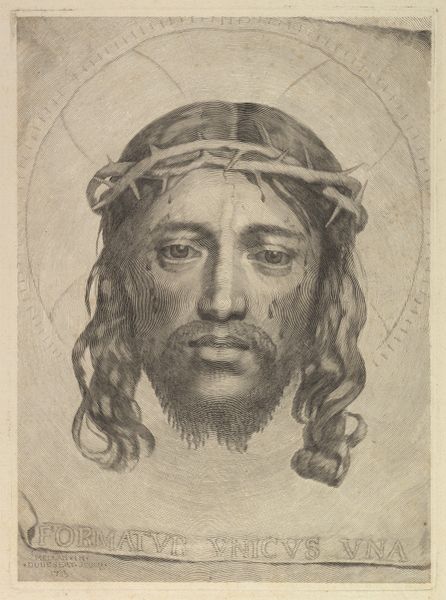

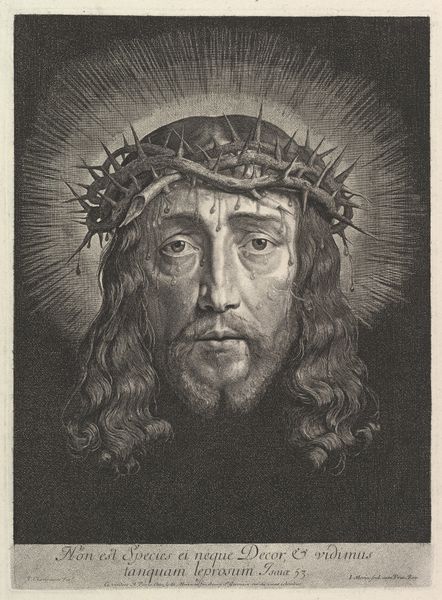

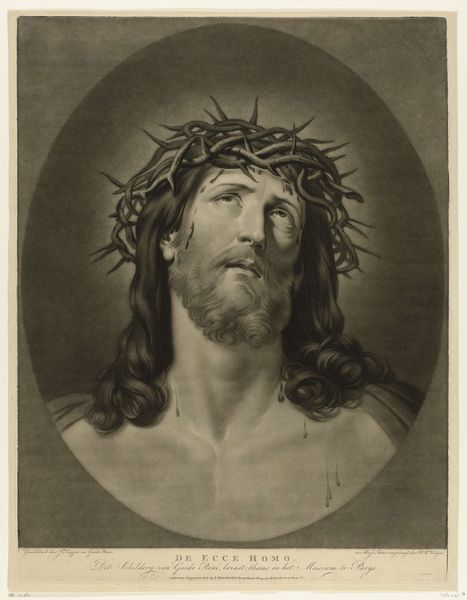

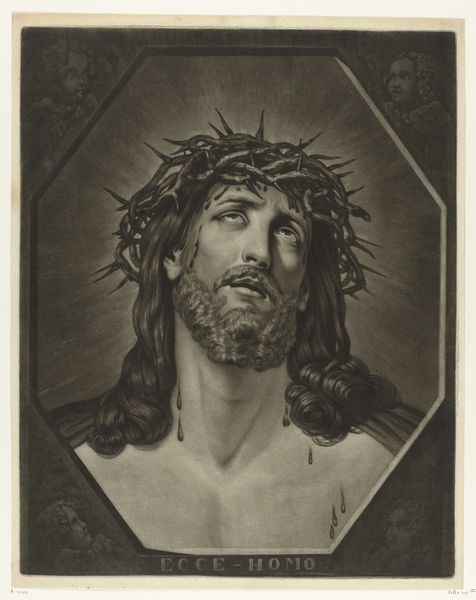

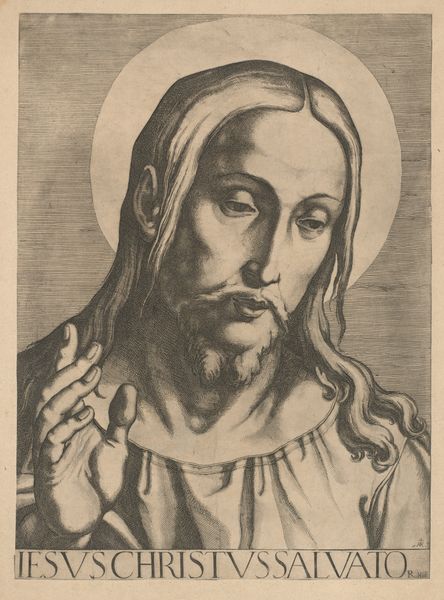

Head of Christ with crown of thorns, in an oval frame with a ribbon above and banderole below, after Reni 1600 - 1700

0:00

0:00

drawing, print, engraving

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

baroque

# print

#

portrait drawing

#

engraving

Dimensions: Sheet (Trimmed): 12 5/8 × 8 5/16 in. (32 × 21.1 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: I find myself struck by the figure's gaze, so vulnerable and uplifted at the same time. There's a powerful emotional charge even through the graphic, almost detached nature of the print. Editor: Indeed. This engraving, “Head of Christ with crown of thorns, in an oval frame with a ribbon above and banderole below, after Reni” made sometime between 1600 and 1700, likely reproduced a painting. Notice the meticulous detail: the fine lines suggesting light radiating outwards, the textures of the crown and ribbons. It’s interesting to consider the skilled labor and tools required to produce such detail using only a burin. Curator: I'm drawn to consider how this image might function within a social and political landscape. Consider the reproduction – making an image widely accessible that may have only been for a privileged few. Did this democratize access to this imagery? The artist's role would be diminished here, no? Editor: Well, that touches upon ideas of authorship and artistic skill. But this piece is credited as “after Reni," meaning that there’s still an artistic genius at the work’s origin. The engraver, identified as Cajetanus Urbinas, acted as a facilitator, of sorts. Think of the relationship of artist, the art market, and how this type of work could broaden the original work's market reach, allowing a mass distribution of faith. Curator: It makes me think about power structures and religious authority during this period, and the symbolic weight an image like this might carry for different viewers. We must question the assumed universality of Christian imagery – its imposition on colonized peoples, its role in reinforcing social hierarchies, and its power to simultaneously offer solace and enforce dominance. Editor: A worthy consideration for sure. Looking closer, the materials, ink and paper, allowed it to exist transnationally and transform how audiences could understand spirituality in the 17th century. It speaks to shifts in cultural consumption, of course. Curator: So, seeing it that way really transforms the idea of a religious token of faith to an interesting vehicle of material production. Editor: Precisely. In a sense, the hand and machine meet here. A mass production for distribution to eager recipients across cultural contexts. A perfect reminder that artwork cannot be disconnected from its material reality. Curator: That provides a lot more perspective for me to carry with me when considering Baroque art and its capacity for diverse interpretations. Editor: Yes, moving beyond just an understanding of beauty, which still applies of course. Thank you, Cajetanus Urbinas, for giving us an object lesson on society itself.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.