engraving

#

allegory

#

baroque

#

figuration

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 319 mm, width 342 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

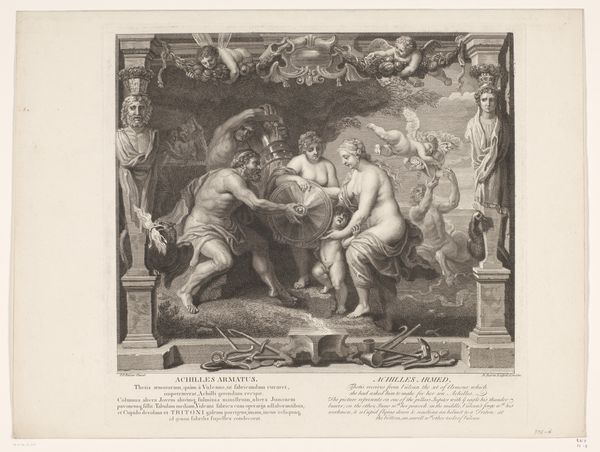

Curator: Franz Ertinger's 1679 engraving, "Thetis receives arms for Achilles from Vulcan" presents a bustling scene, a mythological tableau brought to life with Baroque flair. My first thought is just how much is going on. So much detail, but so meticulously rendered! Editor: It feels almost claustrophobic, doesn’t it? There's this density, an active foreground that almost smothers the narrative. Ertinger definitely captures the drama of the divine exchange but I do wonder about the symbolic impact. Curator: Well, the scene itself is rife with symbolism, isn't it? We see Thetis, the sea nymph, receiving the armor for her son Achilles from Vulcan, the god of the forge. Achilles, of course, is fated to die in the Trojan War, making this moment loaded with a bittersweet tension. The figures surrounding them underscore the historical and mythical heft of it all. Editor: Exactly, and I think positioning this artwork in its cultural and political setting is important. Seventeenth-century art was, after all, enmeshed with power dynamics. Allegorical engravings like this, commissioned and circulated, perpetuated particular heroic ideals and visions of leadership. It is fascinating how Ertinger visualizes this exchange, but the power structure that commissions this work does, indeed, require our critical attention. Curator: I think the engraving style certainly amplifies this. Ertinger used line work to suggest tone, mass and, volume. If you look carefully, he captures the opulence of the scene while alluding to its grave implications through the use of heavy Baroque themes. The fact that we see putti flying overhead reminds me of what lies ahead. Editor: Yet there is more at play here. I notice that Ertinger depicts Thetis at the center; but how is she framed by these narratives of war and fate that mostly focus on men and their glories? How are such classical stories utilized to subtly reinforce patriarchy, making even mothers like Thetis seem almost props in masculine plots? I always find something very poignant, for instance, in knowing that these objects are housed in the Rijksmuseum, formerly representing Dutch colonial aspirations. Curator: I appreciate how you consider what a museum embodies; how these artifacts come to mean different things when a once sovereign state turns to a colonial power. As historians, we consider these trajectories in the production and consumption of these images, their historical context, their impact, the narrative that still drives them to this day. Editor: Yes! By grappling with this intersectional discourse, we come closer to seeing Ertinger’s beautiful image—and, crucially, beyond its most immediate scope, as we draw conclusions between power and portrayal.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.