print, engraving

#

portrait

# print

#

figuration

#

line

#

northern-renaissance

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 167 mm, width 125 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

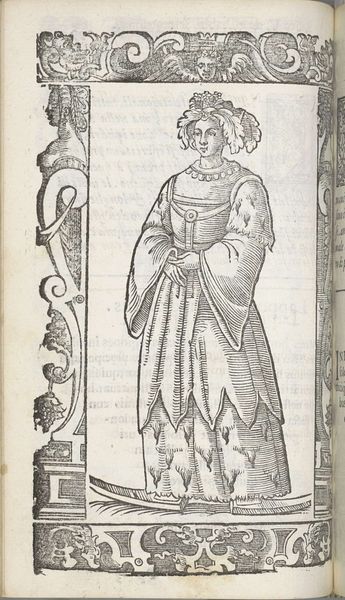

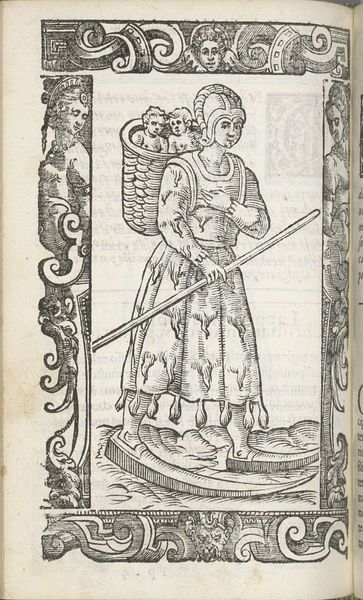

Editor: Here we have "Gentildonna di Brabantia (Flandrensis)", a print made by Christoph Krieger in 1598. It's incredibly detailed for an engraving, with so many fine lines. The woman has this almost ghostly quality to her, emerging from a dark background. What is most striking to you about this portrait? Curator: Well, it's important to remember that prints like this circulated widely, playing a crucial role in shaping ideas about status and identity in the late 16th century. Look at how this "gentlewoman" is framed. Do you notice the ornamental border filled with classical motifs? Editor: Yes, I see cherubs and grotesque masks. It feels…almost like a stage. Curator: Precisely! Consider that the image isn't just a likeness, it's a performance of nobility for public consumption. It also invites us to consider the printing press, not as neutral, but as itself an industry shaped by market forces and reliant on patronage. Where might Krieger have circulated this image? Editor: Possibly amongst other elites, perhaps as part of a series showcasing different regional identities. Would prints like this reinforce existing social hierarchies or challenge them? Curator: Good question! They probably did both. Disseminating images of status inevitably democratizes access to representations of power, even while it reinforces the idea of that power. This "Gentildonna," multiplied and distributed, enters into circulation to be consumed and negotiated within society. Editor: So, a single image becomes a political tool of sorts. I never considered that. I am always so concerned with the “artist” as an individual but here there is more at play! Curator: Exactly. Art doesn't exist in a vacuum; it interacts with societal forces. Thinking about this work really highlights that idea.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.