print, engraving

#

portrait

# print

#

figuration

#

11_renaissance

#

classicism

#

history-painting

#

northern-renaissance

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 42 mm, width 27 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

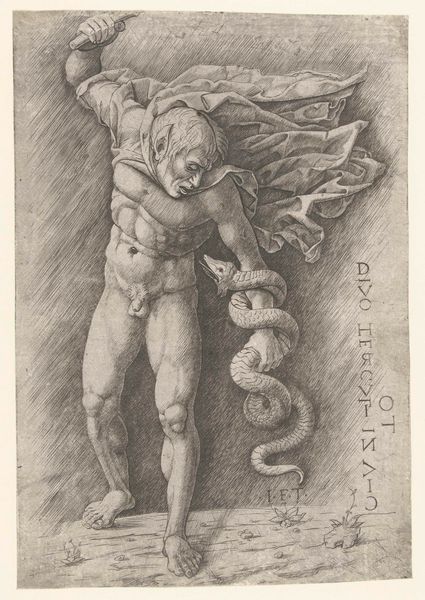

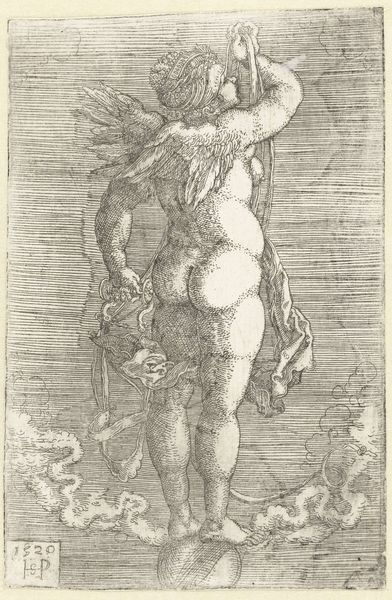

Curator: Here we have "Zeegod op dolfijn" or "Sea God on a Dolphin" by Barthel Beham, created around 1525. It’s an engraving, quite small in scale. Editor: Immediately, I'm struck by the rather strained intensity in the sea god's face. It’s not the triumphant figure you might expect. There’s a lot of labor suggested here, in his muscles and furrowed brow, he seems burdened. Curator: The politics of imagery in the Northern Renaissance were heavily influenced by classical ideals being filtered through a changing socio-political landscape, and prints were an accessible and increasingly popular way to disseminate ideas. Editor: Exactly. Engravings like this demonstrate the labor involved in reproducing imagery and disseminating stories. The clear delineation, the fine lines that build up to create volume, speaks to the process of artistic production in itself. What about the reception of this particular piece at the time? Curator: The circulation of prints allowed for wider audiences than paintings, so artists could reach beyond courtly circles, engaging the rising merchant class. This classical theme offered access to elite culture but in a new, reproducible format that disrupted traditional hierarchies. We have a mythological figure available to the rising merchant classes! Editor: I see that labor and production aren't only reflected in the act of engraving, but also visually represented. His sword, held aloft, suggests power but also exertion. It underscores the act of claiming dominion, of work, not just divine right. Curator: And the figure is noticeably nude, a nod to classical statuary, but also reflecting a German fascination with the body during the Reformation. So how do you think that impacts the way his role is constructed? Editor: Perhaps it signals a rejection of overly ornamental or religious display. The sea god's physical body, his humanity and the human endeavor, are literally exposed, demanding viewers consider the cost – or at least the means – behind power, which resonates well with merchant society at the time. Curator: The themes of mythology provided space to comment on contemporary issues, a safe way to deal with controversial subject matter under the garb of fable and allegory. Editor: Looking at the engraving as a material object, the choices of line, form, and subject coalesce into something that bridges high art with practical craftsmanship, while reflecting emerging class tensions. It’s a testament to the potential of reproduced imagery to reach a far broader social space. Curator: I think that offers us an interesting peek into this historical piece, showing that it's so much more than just classical iconography, and rather represents complex shifts within culture, religion and politics at the time of its production.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.