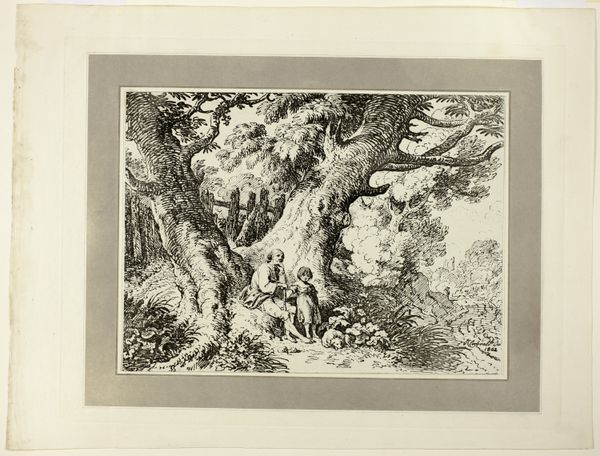

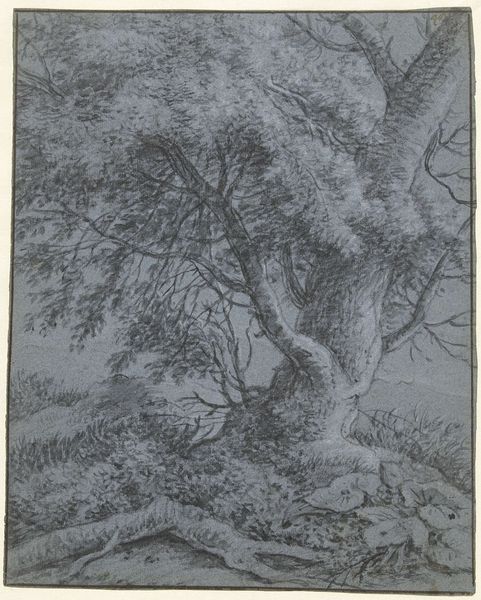

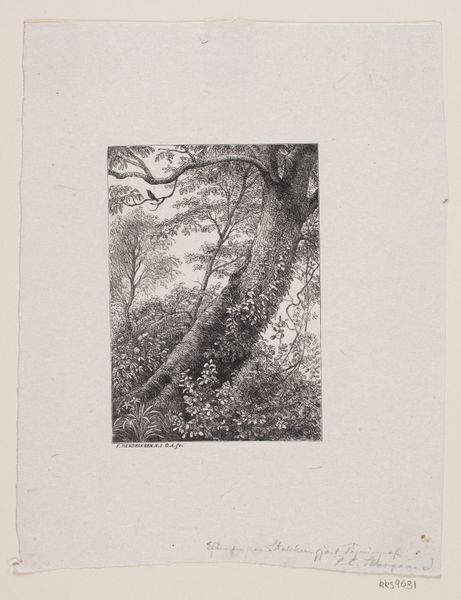

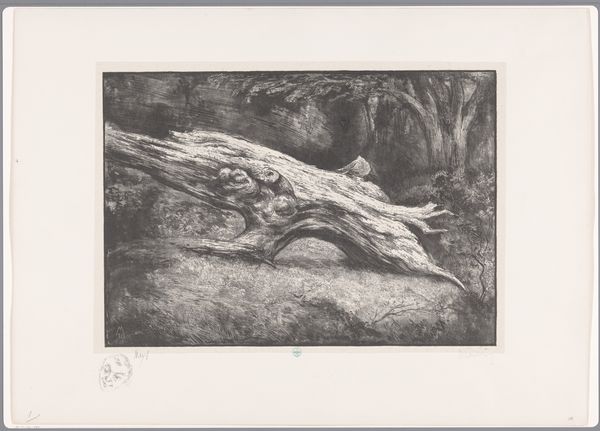

Old Tree, from the first issue of Specimens of Polyautography Possibly 1801 - 1803

0:00

0:00

drawing, lithograph, print, paper

#

drawing

#

lithograph

# print

#

landscape

#

figuration

#

paper

#

romanticism

#

line

Dimensions: 287 × 210 mm (image/primary support); 490 × 375 mm (secondary support)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Before us is "Old Tree, from the first issue of Specimens of Polyautography," a lithograph print on paper, possibly from 1801-1803, created by Thomas Hearne. It's currently part of the collection at the Art Institute of Chicago. Editor: The first thing that strikes me is its texture. It almost feels like a charcoal drawing but with the stark contrast typical of prints. There’s a distinct atmosphere to it, something almost melancholic. Curator: I think the mood arises directly from Hearne’s chosen lithographic process. Remember that lithography was a relatively new printing technique at the time. Its accessibility democratized printmaking, inviting wider participation, including Hearne, who explored its capacity to mimic drawings. Editor: That’s interesting! The relative ease of production makes you wonder who the intended audience was and how they were consuming images like these. This work is so evocative. You see that twisting tree—almost anthropomorphic—and its presence speaks volumes about humanity’s relationship with nature during that era, especially amid rapid industrial changes. The Romantics certainly idealized nature in the face of this change. Curator: Precisely. The tree serves as the focal point, its gnarly form rendered with meticulous detail. The artist uses layering and hatching to create tonal depth and three-dimensionality, further enhanced through his choice of materials, specifically the paper onto which the print is transferred. Did he select that specific kind to give that certain rough and absorbent quality? Editor: The work reflects a very particular view of landscape—nature that feels both powerful and vulnerable. Its rough edges suggest both endurance and a certain precarity in the face of unrelenting pressure. How the work functions, especially through the act of replication and circulation, gives it new potential meanings and perhaps even subversive intent if the means of production becomes too common. Curator: Looking closely, we can almost imagine Hearne at work. Did he collaborate on a project that was intended for scientific examination? How did it circulate at the time? Those details speak volumes about the culture of production surrounding this work. Editor: Indeed. Reflecting on this piece allows one to consider how art shapes—and is shaped by—cultural perceptions of landscape and nature in times of social transformation. Curator: Absolutely. Understanding these contextual details opens up layers of meaning, allowing us to appreciate this image more fully as more than just a landscape.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.