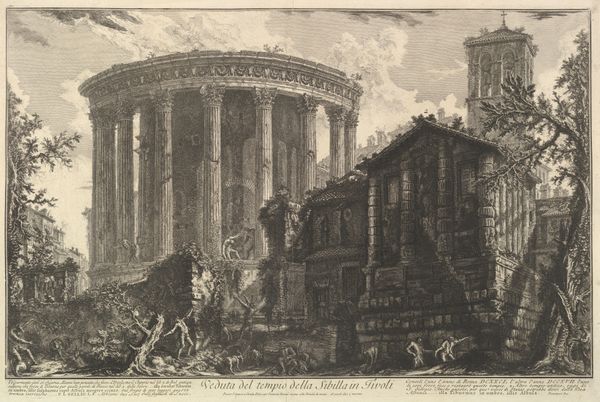

engraving, architecture

#

baroque

#

old engraving style

#

landscape

#

classical-realism

#

pencil drawing

#

history-painting

#

engraving

#

architecture

Dimensions: height 256 mm, width 354 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Standing before us is "Ruïnes te Rome," or "Ruins in Rome," dating from around 1750 to 1770. It’s a fascinating engraving housed here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: Oh, my. It's terribly romantic, isn't it? So much crumbling grandeur juxtaposed with a strange serenity. Like time forgot to keep things tidy. Curator: It's certainly evocative. The artist, Richard Houston, through the engraving process, allows us to peer into a world where classical ideals meet decay. The detail achieved using only incised lines on a metal plate is truly something. Editor: Exactly. And consider what the etching medium, with its inherent reproducibility, meant for circulating these ideas. Think of all the hands that touched the plates, the paper, and eventually, held these images! The engraving becomes a democratizing force, disseminating Roman visions across Europe. What inks were used? Who prepared the paper? So much untold history. Curator: Precisely! Houston captures the aesthetic fascination with ruins, turning remnants of classical architecture into a stage for quiet contemplation, a rather Baroque sensibility, don't you think? See how those figures are almost posing, reclining amidst the wreckage as if they are extras in some elaborate drama? Editor: Perhaps less a stage and more a resource? These figures are situated amongst broken architecture with its beautiful fluting and decorative carving. Was the function of that material still at the forefront of their mind or was it aestheticized for those privileged enough to consume art and philosophy? Who built these structures? And who brought them to ruin? I can't help but wonder if the focus on grand images obscured the everyday building blocks in society that enabled it. Curator: An important point, indeed. There is a prevailing melancholic aura, hinting at the transience of power and the inevitable passing of even the grandest empires. A morality lesson, if you will. Editor: I suppose what Houston offers us with his process of production and these forms are a stark vision, simultaneously lamenting and celebrating what once was. Curator: Beautifully said. It's a testament to the enduring power of art to spark such reflection, even centuries later.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.