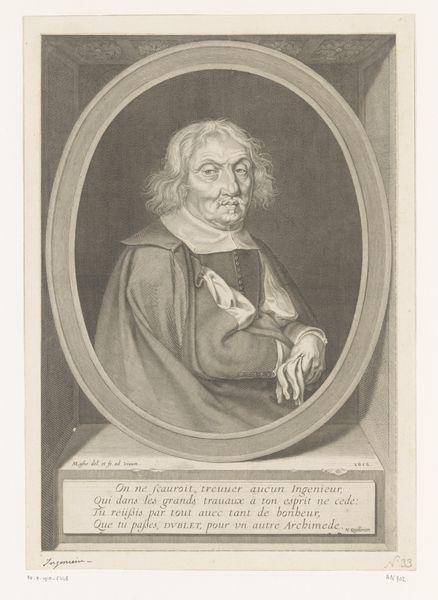

Dimensions: height 146 mm, width 86 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have Louis Bosse’s "Portret van M. de Malon," an engraving dating from around 1767 to 1777. It’s quite a detailed print, and the figure appears very dignified. What strikes you most about this portrait? Curator: I'm immediately drawn to the engraving itself as a material object and process. Think about the labour involved in creating this intricate design by hand, carving lines into a metal plate. This wasn't just about portraying an individual; it was about demonstrating skill and participating in a specific mode of production. Editor: So you see the value in the physical act of creation, instead of, let's say, the figure represented? Curator: Exactly! How does the choice of engraving as a medium affect the social context? Engravings allowed for wider distribution of images, and a relatively cost effective approach for widespread representation and, indeed, propaganda. Who had access to engravings? How did this differ from oil paintings reserved for the elite? Editor: So it’s more about who *could* have this portrait, than who *is* in the portrait? I see your point about accessibility; printmaking democratizes the image, doesn’t it? Curator: Precisely! Also consider the materiality of ink and paper itself. Paper became a conveyor of so much political material - its ubiquity can almost make it invisible to the eye of art history! The availability of the artwork due to these new processes affected everything. Editor: That is interesting. I've always looked at art with an aim of considering it symbolically. I will certainly think more about materials going forward, and the implications for artistic consumption.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.