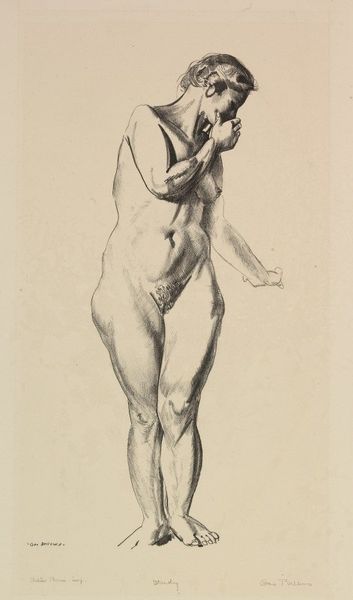

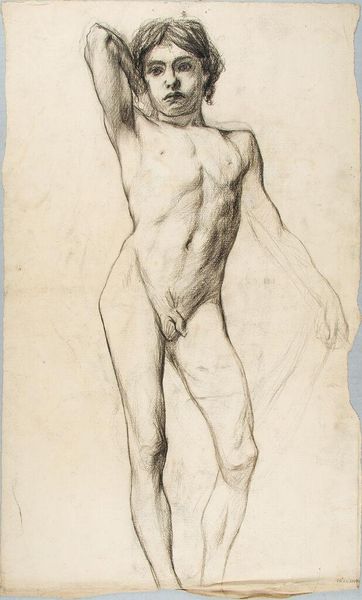

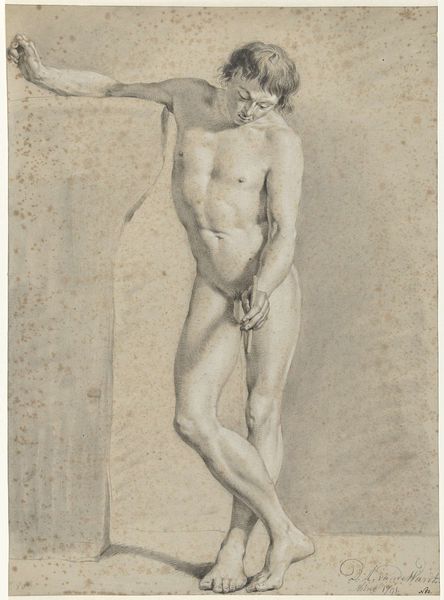

drawing, charcoal

#

drawing

#

baroque

#

dutch-golden-age

#

charcoal drawing

#

charcoal

#

charcoal

#

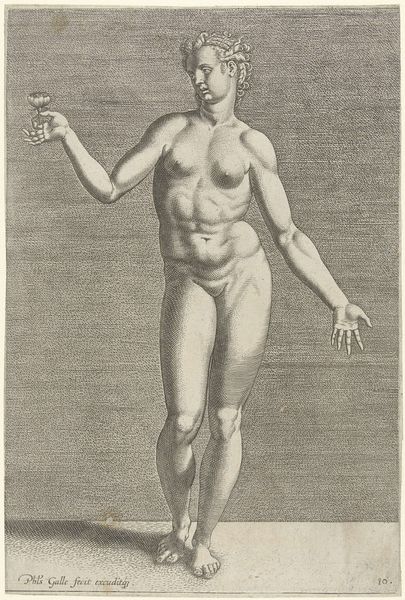

nude

Dimensions: height 327 mm, width 208 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have Moses ter Borch's "Geboeide, naakte slaafgemaakte man," or "Bound, Naked Enslaved Man," believed to have been created between 1657 and 1659. It's a charcoal drawing. Editor: My initial impression is one of intense vulnerability. The posture of the figure, the soft gradations of charcoal, everything conveys a feeling of constraint and submission. Curator: Absolutely. Ter Borch's choice of charcoal as a medium is fascinating here. It’s a relatively inexpensive material, widely accessible. This drawing wasn’t intended as a display of wealth, but rather perhaps a study. Its very creation is tied to a particular mode of observing the world. The availability of charcoal itself is linked to deforestation, colonialism, the availability of materials and labor of production of art. Editor: The binding is such a clear visual signifier, isn't it? But look how it contrasts with the classically inspired nude figure. There’s a dissonance there. Enslavement robs the figure of the idealized beauty of antiquity but the composition alludes to ancient classical statues that held powerful emotional and cultural memory regarding European identity. Curator: It speaks to the function of the enslaved body – to be molded into a shape, a position that served someone else. And Ter Borch himself, his position within Dutch society at that time, gave him a very specific lens. His access to such a subject matter reflects the Netherlands involvement with global trade, which heavily depended on slavery in colonies. The production of this drawing then hinges on this social framework. Editor: Yes, and consider the power of the image itself to elicit emotions across generations. The enduring iconography of bound figures, reaching back through millennia, still evokes these sensations of forced subjugation and loss of individual sovereignty. We can project this history on an anonymous body portrayed. Curator: I agree, and it becomes an important object to confront the structures that facilitated its creation and the ongoing ramifications they hold, regarding colonial power dynamics within art. Editor: Looking at it now, I appreciate even more how those emotional echoes can resound across history. Curator: Indeed, it encourages one to reconsider the function and cost of artistic expression.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.