print, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

# print

#

old engraving style

#

personal sketchbook

#

19th century

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 207 mm, width 167 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

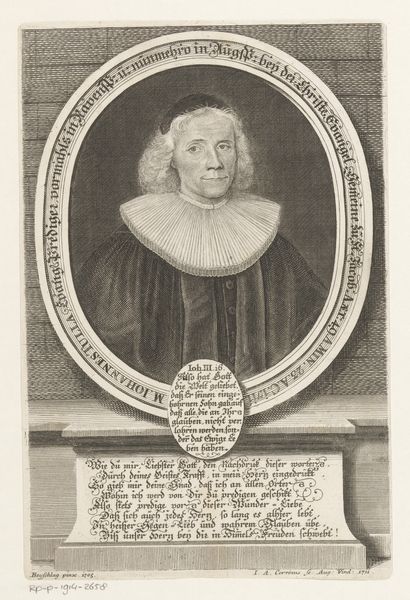

Editor: So, this is "Portret van Johann Ernst Schadaeus," an engraving from sometime between 1696 and 1720 by Johann Alexander Böner. The detail is amazing. I'm struck by the gravity of his expression and all the symbolism packed into such a small space. How do you interpret this work? Curator: Well, situated within its historical context, this portrait serves as more than just a likeness; it functions as a powerful statement of identity and status in the Baroque era. Böner's strategic choices emphasize Schadaeus's authority as a religious figure, which demands an examination of the era's rigid social hierarchies. Note the cross he holds, alongside books that signify theological knowledge; consider how they communicate not just religious devotion but intellectual and institutional power. What implications might this have given the ongoing religious and political conflicts of the time? Editor: That's interesting! So the cross and books aren’t just props, they’re tools to project a specific image. How does the text incorporated into the print factor into this reading? Curator: Exactly. The text beneath the portrait, Vere Herculis Scholastici vides umbram..., directly links Schadaeus to Hercules. What does this suggest about how Schadaeus, or perhaps Böner himself, wanted him to be perceived? It's likely not just a testament to his strength but also to his wisdom and virtue – essential qualities for someone holding religious and pedagogical authority. How do you think this comparison shapes our understanding of his role and the societal expectations placed upon him? Editor: It makes him almost…mythical. Like he's being presented as this larger-than-life figure, upholding intellectual and religious ideals in a turbulent time. It's all so deliberate! Curator: Precisely. And thinking about it further, we might also question the inherent biases within such depictions. Whose voices are amplified, and whose are silenced? This can help us to analyze whose stories are being told and from what perspective, leading to richer understandings about societal norms and power structures of that era. Editor: I never thought about it that way. Seeing it as a constructed narrative of power shifts my perspective completely. Curator: Absolutely. By considering these aspects, we begin to unravel the layers of meaning embedded within seemingly straightforward portraiture, revealing insights into the complex interplay of identity, power, and representation in the 17th and 18th centuries.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.