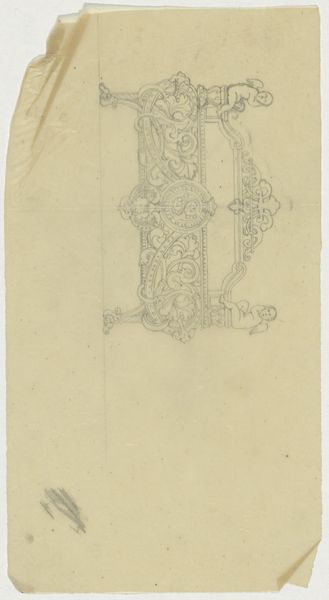

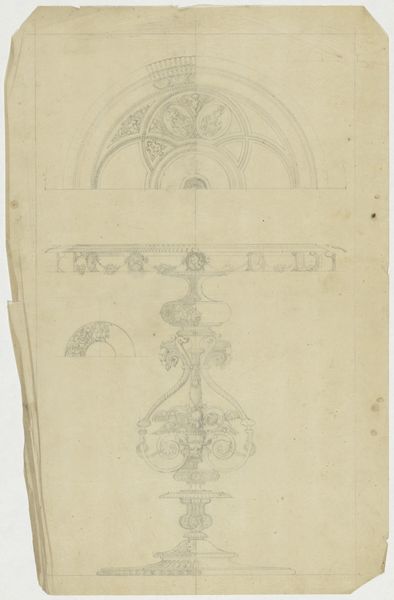

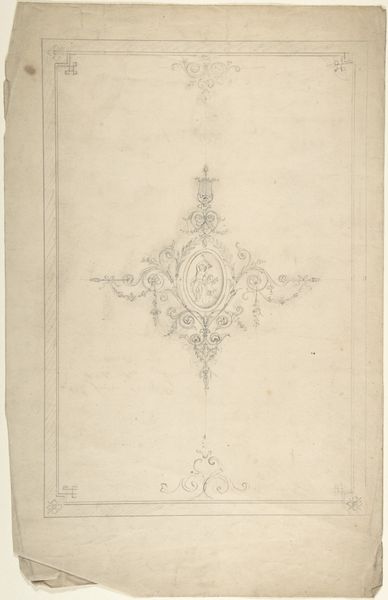

drawing, pencil

#

portrait

#

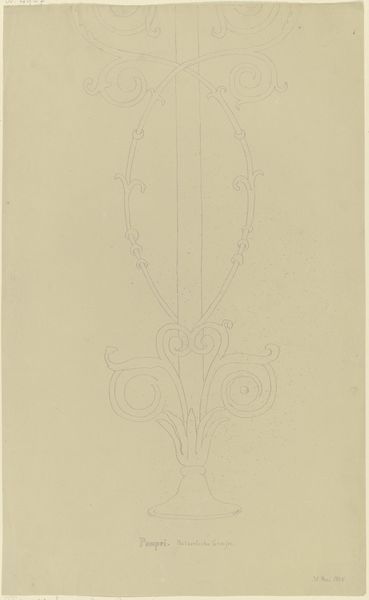

drawing

#

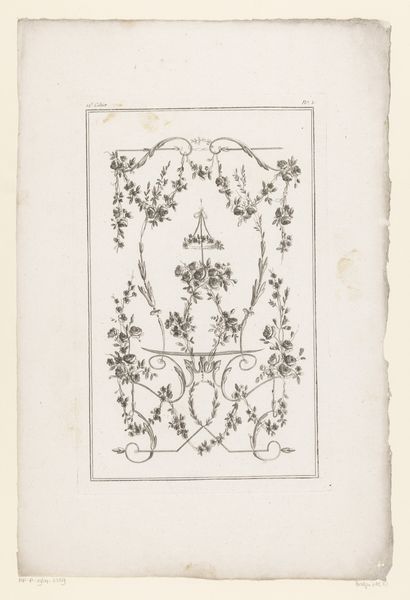

neoclacissism

#

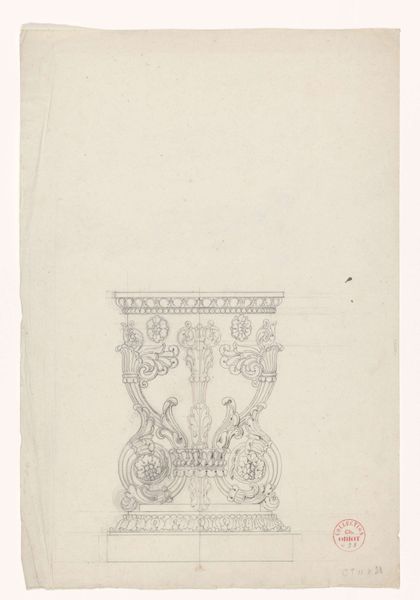

figuration

#

pencil

#

nude

Dimensions: height 98 mm, width 146 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: So, this is "Medaillon," a pencil drawing from around 1830 to 1850, attributed to Firma Feuchère. It’s quite intricate; you've got a nude figure surrounded by putti in a decorative frame. It almost looks like a design for something functional, rather than just a drawing. What do you see in this piece? Curator: This drawing exemplifies how the perceived divide between ‘high art’ and craft collapses when you consider the means of production. It’s not merely a pretty picture, but most likely a preparatory design. Its materiality—pencil on paper—suggests an object meant for reproduction in another material, perhaps metal or porcelain. Think about the labor involved: the draftsman, the artisans who would translate this design. Who would consume the final product, and what social messages would it convey about status and taste? Editor: That's a good point. So, you're saying it’s less about the artistic merit and more about the social and economic factors? Curator: Not entirely, but those factors heavily influence its meaning. Neoclassical motifs were frequently used in decorative arts for the wealthy. But by examining the use of readily available material like pencil, its means of production are revealed to have a different, maybe contradictory story. It presents an idealized vision through a very earthly means, making the goddess accessible, attainable almost. Editor: That’s a perspective I hadn't considered. I was so focused on the mythological aspects, I missed the material reality behind it. Curator: Art history often separates design from artistic expression, which can prevent understanding that materiality can blur hierarchical barriers that historically separate "art" from craft. What can studying its physical origins tell us about class structure and gender roles of the 19th century? Editor: So it’s a social document as much as it is a work of art. Thanks, I learned a lot looking at it that way!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.