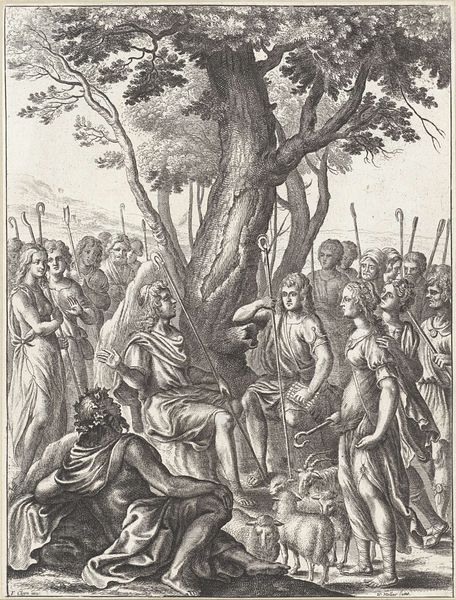

Rebekka bedekt zich met een sluier bij het zien van Isaak 1728

0:00

0:00

gilliamvandergouwen

Rijksmuseum

print, engraving

#

narrative-art

#

baroque

# print

#

old engraving style

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: width 218 mm, height 360 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

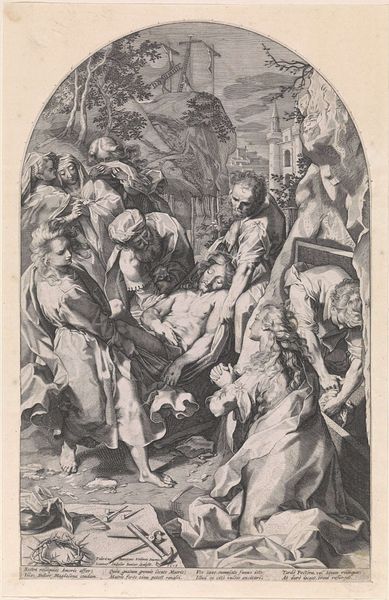

Curator: Standing before us is "Rebekka bedekt zich met een sluier bij het zien van Isaak," or "Rebekah covering herself with a veil upon seeing Isaac," a print made by Gilliam van der Gouwen around 1728. It's currently held here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: The first thing that strikes me is the contrast. The detail of the engraving is exquisite, but the emotional tone is...muted? I almost expect some sweeping gesture, some theatrical drama, but it feels more restrained. Curator: I agree, the baroque period often employed theatrical flourishes. However, here we have a focus on the precise rendering of the biblical narrative, situating Rebekah's encounter with Isaac, her soon-to-be husband. Considering marriage as a societal and often legally binding commitment within a heteronormative structure is really a foundation in discussions of patriarchal social and cultural practices. Editor: It’s a compelling moment of social history, absolutely. What's intriguing is how van der Gouwen represents the very act of veiling. The veil is more than a piece of cloth; it signifies societal expectations, the construction of modesty, female submission within arranged marriage contexts, perhaps even religious observance of such customs. How does it make you consider female visibility and agency at this time? Curator: Exactly! We see the ways in which the woman is both seen, the focus of this entire procession really, and simultaneously un-seen—veiled as an act of submission and conformity to male figures nearby. This depiction begs to engage in dialogues about women's roles and the socio-political frameworks surrounding women in the domestic sphere that transcend this print's moment of production. Editor: Let’s also think about how institutions like the church likely commissioned and shaped the circulation of imagery depicting women through similar lenses to teach moral principles and norms. That engraving’s existence further reinforces this pattern. Curator: I can’t help thinking of what these representations did to enforce particular behaviors, the long-lasting implications they held, especially in relation to women internalizing the weight of expectations and their positioning relative to men. Editor: It speaks volumes to how carefully we must examine these representations, their sources, and their place in both art and societal history. Curator: Exactly. Recognizing those nuances moves us closer to not repeating detrimental interpretations of identities and expressions in media from our past and into the future. Editor: I agree. By teasing out these narratives, we’re given new access to this beautiful image, the better for contextualizing the narratives in the present day.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.