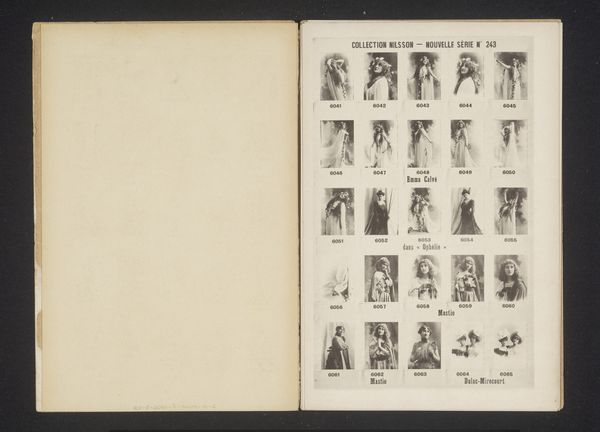

25 portretten van Olive Morrell, Margaret Ruby, Enid Spencer-Brunton, Birdie Sutherland, Beatrice Jeffreys en Ethel Myers before 1899

0:00

0:00

print, photography

#

portrait

# print

#

photography

Dimensions: height 239 mm, width 153 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

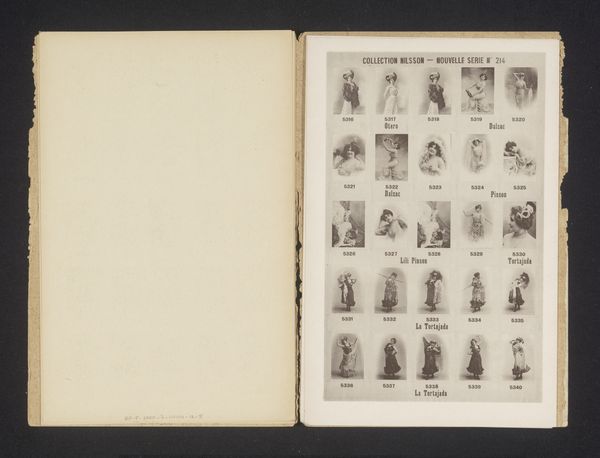

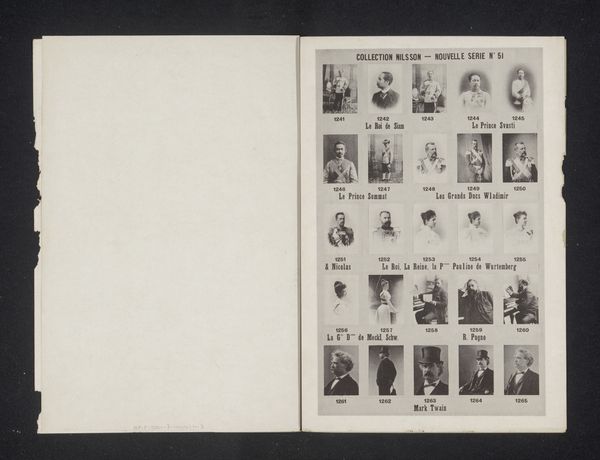

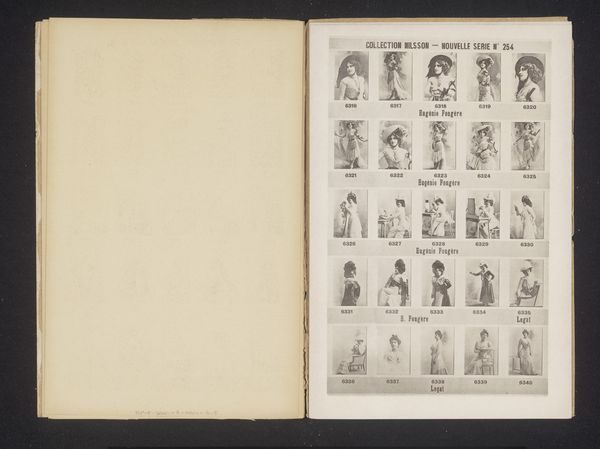

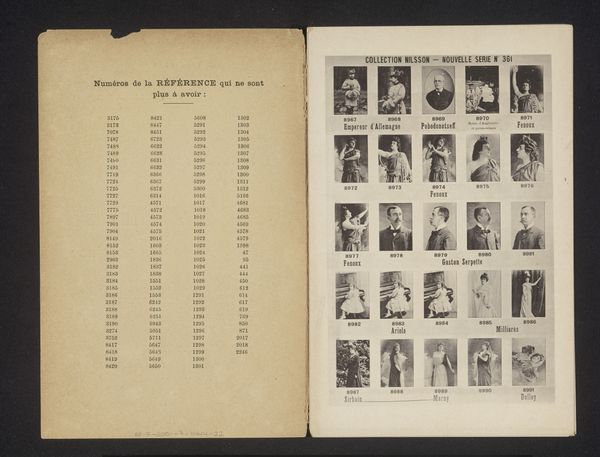

Editor: This artwork presents "25 portretten van Olive Morrell, Margaret Ruby, Enid Spencer-Brunton, Birdie Sutherland, Beatrice Jeffreys en Ethel Myers", dated before 1899. It's a photographic print featuring many small portraits. There’s something fascinating about seeing these faces collected together like specimens. What stories do you think this image is trying to tell? Curator: I think the image prompts us to consider the gaze and power dynamics inherent in portraiture, especially concerning women. We must analyze this 'Collection Nilsson' within the broader context of the era – pre-1900. Photography was democratizing representation, yet these women seem presented as types. Who was Nilsson, and what was his objective? Was he seeking to document the rising middle class, or reinforce pre-existing beauty standards? Notice their poses, the uniformity of presentation, and consider the degree to which these women are active participants in shaping their own image versus being subjected to someone else's vision. Editor: That’s a great point about agency. I hadn’t really considered that. Are the subjects’ expressions conveying how they perceive themselves or just presenting as demure young women? Curator: Precisely. Do you notice how they're all 'Miss' something-or-other? This denotes their marital status and social standing – their identities largely defined by their relationships to men, or the lack thereof. Even their names become labels, part of a collector's set. It is through this lens we can start understanding gender inequality issues concerning their societal expectations in pre-1900s, issues about image and identity in the era that echoes with contemporary times. Editor: That really shifts my understanding of the work. It is no longer just a series of pretty faces but a record that hints at social restrictions. Curator: Exactly! It encourages a conversation that questions the representation and perception of women. The image functions almost as an early form of media – dictating a narrow standard. What have you learned that connects from the historical image and contemporary experiences about women's rights? Editor: Well, I see that the fight to have control over one's image is nothing new and still going on. I'll carry this in mind every time I now view artwork in museums or in contemporary galleries. Thank you.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.