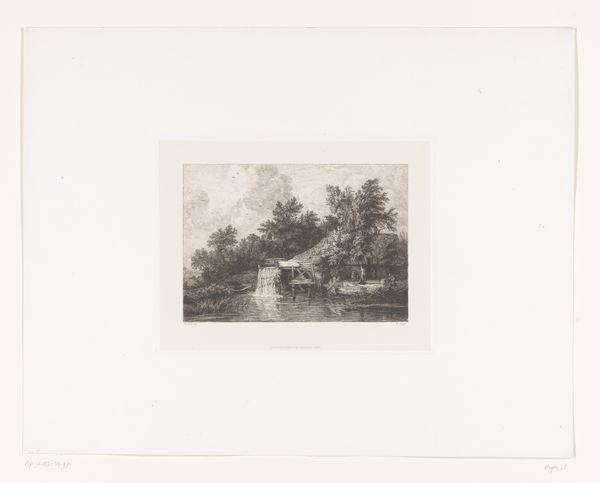

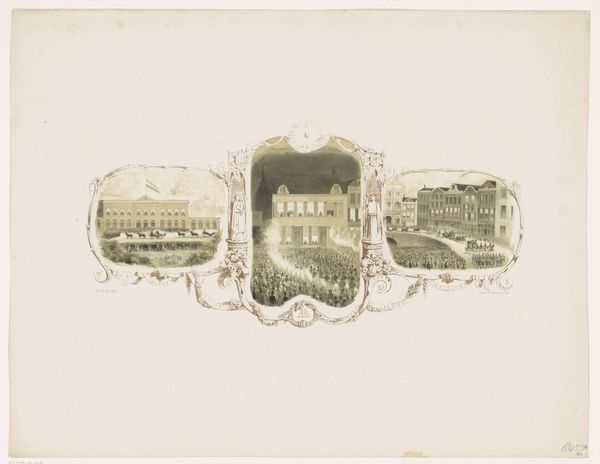

Het kantoorgebouw van de Firma Sluyters & Co. Kali Besar Batavia 1919

0:00

0:00

drawing, print, etching, pencil

#

drawing

#

water colours

# print

#

etching

#

asian-art

#

landscape

#

intimism

#

pencil

#

cityscape

#

watercolour illustration

#

academic-art

#

realism

Dimensions: height 465 mm, width 526 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: This is Wijnand Otto Jan Nieuwenkamp's "Het kantoorgebouw van de Firma Sluyters & Co. Kali Besar Batavia" from 1919. It’s an etching, and the scene, I think, captures a bustling marketplace along the river. What strikes me is the detail and almost documentary feel to the work. What do you see in it? Curator: Well, the image, rendered through etching, a printmaking process involving acid, captures a Dutch trading post. Consider the materials employed - the paper, the etching ink. These weren't just artistic choices, but commodities themselves, connected to global trade networks and the exploitation of resources in places like Batavia. The “high art” rendering is itself dependent on the materials extracted and manufactured, reflecting colonial economic practices. Editor: So you're saying the print isn't just a picture of a place; it's an artifact of the colonial system that produced it? How does the artistic choice play into that? Curator: Precisely. The technique is also relevant. Etching is reproducible and was crucial for circulating images and constructing colonial narratives. Also consider who likely owned these prints; what social classes and markets would value these as consumer objects? It allows us to investigate production of both capital and also of “taste.” Editor: I see. So the image itself is bound up in material history, a record of sorts but also complicit within that historical context. Thanks for highlighting the colonial-era production. Curator: Indeed. By examining the etching’s creation, circulation, and consumption, we gain insights beyond its mere depiction.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.